A memory: age about 25 or 26. Living in Australia’s far northwest. Working in the only hotel in a tiny isolated iron ore mining town. Along with a group of friends driving an hour through the desert to Millstream Tavern – even more isolated but existing because of the water, a natural oasis in a dry orange-red land. Swimming. Swinging ourselves into the water with a long rope dangling from a tree. Sitting by the water talking, laughing, drinking. Joe, the wild Mexican, shouting Riba! Riba!

Another memory: another tiny isolated iron ore mining town. Christmas day. All the hotel staff pack eskys (coolers) full of food, and a keg, an entire hotel-size keg of beer, and drive to a river in a cool canyon in the red desert, and we haul all our stuff, including the keg, down into the canyon, and spend the day there. By the water.

The people of this huge dry continent, the driest continent, subject to years-long droughts, and raging floods that treat cars as play things, have a convoluted connection to water. It is everywhere. It is nowhere. Even people who live in the arid centre or in the thousands of kilometres of the western desert know where the water holes are – the deep canyons found in the desert with ice cold water at the bottom.

And then there’s the coast that defines the nation. 60,000 kilometres (37,280 miles) of coastline. Nearly 12,000 beaches. 85% of Australians live within one hour of the beaches that ring this island continent. The nation is literally defined and constrained by access to coastal water, to safe protected bay beaches, to raging surf beaches, to long empty stretches of golden sand.

To be clear, when I talk about a beach I mean something that looks like this:

or this:

or this:

When summer comes almost everyone has about six weeks to play. The question flies around: Where are you going for the hols? The question’s unspoken implication is which beach?

Australia always has been a largely egalitarian society, and this is never truer than at the beach. For Australians the beach is the symbol of freedom and independence. No one cares who you are or what you look like, there’s no judgement, or discrimination on the basis of age, or race, or religion, or what your body looks like. There’s just play;

and relaxation;

camping out for the day;

and dawdling and gabbing at the water’s edge;

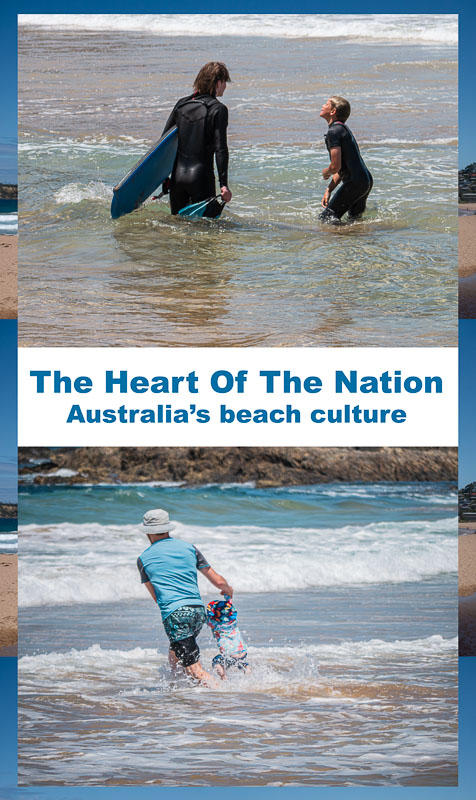

swimming and surfing;

building sand castles, and boogie boarding;

skimboarding;

hurling yourself off the bridge;

hurling yourself into the surf;

or simply sitting watching the waves arrive and recede. The beach doesn’t care about you or your worries. It just does what it always does, soothing in its ceaseless rhythm of in and out. There’s no better place than a beach to quiet a troubled mind.

Children are introduced young to the joys of the beach,

and just about everyone in this multicultural society finds a way to enjoy the water.

For most Australians the beach is filled with childhood memories; it’s often the place of first teenage crushes and rites of passage; many older Australians retire there, and have their ashes scattered into the surf; marriages, birthdays, and all kinds of celebrations take place at the beach.

To a large extent the culture of a country is shaped by the environment. Canadians and Scandinavians learn about ice and snow, skating and skiing and snowshoeing the same way that Australians learn about the beach and water, swimming and surfing and jumping off cliffs into deep pools. With little history, and most Australians caring little for history anyway, the beach is in large part the glue that binds the country together, and is probably the most potent defining principle of the national psyche: freedom and independence and she’ll-be-right-mate and no-worries. Whatever else is happening there’s always the beach.

I remember being absolutely stunned when I learned that in other countries people could own the beach. We’re not allowed to swim there? We have to pay? That can’t be right! How can you own a beach? To an Aussie owning a beach feels as if the world has somehow shifted off its axis, like something has gone terribly wrong. Beaches belong to everyone!

It’s February 2023. School hols are over, and everyone’s gone back to work. The beaches are mostly empty by the time we drive the two hours from Canberra to Batemans Bay, the gateway to Canberra’s beaches. It was unthinkable that we would go to Australia to visit family and not spend time at the beach.

From Batemans Bay, go 50 kilometres along the coast in either direction and you’ll find about 140 sand beaches. They range in size from tiny unnamed coves of a hundred metres or less to the 2.5 kilometres of Long Beach. We’ve rented a house in Malua Bay, me and Don and my three sisters and brother-in-law. The house is a five minute walk from the beach, a 500 metre stretch of golden sand and rolling waves. It’s the first good surf beach you come to after heading south from Batemans Bay.

We’re at the beach for part of every day, except for the days we drive ten minutes to Broulee Beach. It’s here that Candlagen Creek empties into the sea forming a calm lagoon.

And it’s here that the kids hurl themselves off the road bridge above, and learn all kinds of water activities in calm water.

Just on the other side of the creek is the glorious two kilometres of Broulee Beach. It’s mostly quiet when we are there, but on the weekend the crowds arrive from Canberra giving some idea of what it’s like at the height of the summer season.

There’s a dichotomy about Australian beaches. They are held within the collective psyche almost as sacred, and yet they are probably the most hedonistic places in the country. They can be dangerous, but not dangerous enough to hold us back; their siren call can’t be ignored. We’ll be careful we say. We’ll swim between the flags, and lookout for rips. We care more about what the sea can give us than what it can take, in an instant.

Another memory: I’m about 15. I’m at the beach with a couple of friends. The details are hazy, but this is clear – me and a girlfriend are watching our friend surf. One of us sees a shark fin. Or thinks it’s a shark fin; with the heaving up and down of the waves it’s hard to tell. But what if it is?! We start screaming. And screaming. And screaming. On and on, trying to get his attention above the noise of the sea. There’s no one else around; we’re alone on a deserted beach; there’s nothing else we can do. An eternity goes by; we’re growing hoarse. Then suddenly he hears us and comes in. And the shark, if there was one, has gone.

Malua Bay is the headquarters of the Batemans Bay Surf Lifesaving Club. There’s a shark alarm there. During the season there are lifesavers on the lookout who sound the alarm as necessary. There’s also drone surveillance all summer provided by Surf Life Saving NSW whereby operators are able to spot potentially dangerous sharks.

Plus there’s this: There are 305 SMART (Shark-Management-Alert-In-Real-Time) drumlines along the NSW coast (and a dozen or so in Western Australia and Queensland) that are set every morning (weather dependent) and collected before sunset. The drumlines catch actively feeding sharks using bait. When a shark is caught SMART contractors receive an alert. They then respond to tag and release the shark around one kilometre offshore. Tagged sharks can then be detected by listening stations across the NSW coastline when they swim within 500 m of the unit. Between Batemans Bay and South Broulee beach, a distance of 22 kilometres, and with eight popular beaches, there are fifteen drumlines, and two drones patrolling the area.

I’ll just say that again: eight good beaches in only 22 kilometres.

But really, sharks are not that big a problem. In the last fifty years, there have been only sixty deaths from shark attacks. There are two to three deaths every year from bee stings. But sometimes the fear is real.

Rips are a greater danger than sharks. All that water coming in has to go somewhere, and being water it falls into the lowest parts of the terrain creating a channel, and flows out to sea from there. Getting caught in a rip can kill you because a rip will pull you out with such speed and power that even the strongest swimmer can’t fight it. There are two rips at Malua Beach, and about thirty rescues each year. If you find yourself in a rip or in trouble in the water, hold one hand up in the air. This is the signal for the lifies to come and help. Splashing around won’t get their attention as quickly.

But ultimately none of these dangers matter. Australia’s love affair with the beach endures because the elemental sensuality of the surf, of water, and its ability to calm and renew will always be worth it.

You can find all Australia at the beach – in the multi-generational families having picnics, the slender barely-clad teenagers, the wetsuit-clad surfers of all ages, hijabbed women having a conversation while up to their hips in the surf,

mum and dad and the kids on holidays (because the beach is where all holidays happen!),

visiting Sikhs with their local guide,

sunburnt people and fully-clothed people, parents teaching the nippers how to swim before they can even tie their laces, the beer-bellied middle-aged man and his missus under an open-sided dome tent, shirtless teenagers drinking beers and kicking a ball around. The beach, at the literal edge of the country, is Australia’s transcendent heart, a numinous place in a nation of down-to-earth prosaic people.

We come from water. Our cells are 70% water, and when the body is immersed in water the cells remember. Being in water is the closest we can get to home. And for most Aussies that’s what the beach is. Home.

Batemans Bay, Malua Bay, and Broulee Beach are all situated on what was and always will be Aboriginal land; the land of the Yuin Nation.

Next post: I can hear all you dog-lovers asking Where are the dogs? Coming up – a photo essay of dogs at the beach. And after that Surf Life Saving Australia – the biggest volunteer organization in the world, followed by: Surfers! A photo essay.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

Beautiful, descriptive, idyllic, and perfect! Thank you! 🌊 I’ve always wanted to visit Australia!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m glad you enjoyed it, and I hope you get to Oz one day!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome, Alison! Me too! Karla (not Dorothy tee hee, ) and her little dog, Finley, too! 🐾

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous post – absolutely nailed it 🙂 x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Annie. It was a fun post to write.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Alison, I loved this post – you have captured it all perfectly – except perhaps the horrific number of drownings in coastal and inland waters this summer. I also loved your post about living post stroke and coming to terms with loss – as we all have to one day. I’ll see if I have your email and send you a pm. All the best for 2024. Best wishes, Helen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Helen. The whole beach thing is so huge in Oz, and I had hundreds of beach photos so it became clear the direction I needed to go. Plus we came upon a SLS carnival, which I’d never seen before so that was really cool. I didn’t know about all the recent drownings.

Don’s stroke sure changed things for us, though he is well now and except that his short-term memory is a little (more) wonky you’d never know he’d even had a stroke. He was very lucky to get no paralysis. Still it has certainly led to a reckoning for both of us. I’ll email you so you have my address.

All the best for 2024 for you too.

Alison

LikeLike

What a wonderful essay and it’s so true.

Our school holidays were spent caravaning with another family at the beach. Another memory to add is the dusk walk along the beach with the 4 adults and 4 children jumping the waves and then, watching the sun go down.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Vicki. I’m glad you enjoyed it. And your memories sound pretty wonderful. We never went caravanning, and I think I’d have loved that. As a young adult I remember camping at a couple of different beaches on Canberra’s coast.

Your memory of the dusk walks sounds so lovely.

Alison

LikeLike

Home. Love this post. And hi you two. ❤️🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paulette. I love that you love it ❤️

And hi right back ❤️🙏

Alison

LikeLike

Your love for Australia and its beaches come through loudly in your words. Love to hear your memories that embedded them in your heart. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Maggie. You never know where life will lead you, and I never though I’d end up emigrating to Canada, but here I am. I’ve been here 40 years and am Canadian by now I suppose, but I’ll always be an Aussie, and miss it. Such is the life of an expat.

I have so many memories of my youth there – and summer was always at the beach.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looking at your beaches, Alison, I ask myself how come I never made it to Australia? Once there was the opportunity- a hostel sharing friend was emigrating and I thought briefly about it. But I was in love with a guy from the East End of London, a fairly new and heady romance and I couldn’t countenance leaving. I guess it wasn’t meant to be, but I do so envy those beaches. Perhaps a younger me would have conquered my fear of water there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a pity that you never got to Oz, but I certainly understand the pull of young love, especially when it’s new – I felt it myself a time or two 😁

Australia’s beaches are truly spectacular. I’m sure the combination of the beaches and the culture would have been enough for you to get over your fear.

Instead you have your beautiful Algarve – which I have yet to see. One day . . . . .

Alison

LikeLike

There’s enough beautiful world for all of us, isn’t there, but some of us are luckier than others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed that’s true. I feel so blessed.

LikeLike

🤗🩷

LikeLike

Next time come to our beach at Rosedale; not far from Broulee.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely! I’ve heard of Rosedale but never been there (I don’t think). Next time!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic post with so many amazing photos, Alison. As avid surfers and beach lovers, we would feel right at home along Australias scenic coast. I’ve watched a few episodes of Bondi Beach rescue series and loved following the daily lives and routines of the professional lifeguards who patrol Bondi Beach. I quickly learned that being a good lifeguard is physically challenging as you have to be in good shape. Thanks for sharing, and have a good day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Aiva. I hope you get to Oz one day to surf one or two of those fabulous beaches.

I didn’t know about Bondi Rescue! I will definitely be watching some episodes over the coming nights. Thanks for mentioning it!

Alison 🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful photo tour! My favorite photo? The black-and-white image of the boys, one head up, one head down is a stunning capture. Here, where February is ready to begin with snow all around, these photos are welcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

I too like the photo of the two boys jumping – I watched for a while as one after the other, or sometimes two at a time, many jumped off the bridge. I was pleased to catch these two as they flew down together.

I’m in Vancouver where we are expecting a huge downpour tonight and tomorrow, so I enjoy these summer photos too.

Alison

LikeLike

This is such a heartfelt ode to Australia’s beaches, Alison. And yes, those are real beaches in my book too! I like your comparison between Australians and Canadians in terms of their attachment to their environment. Since you’ve been living in Canada for so many years, I wonder if you’ve embraced the snow more than the beach now. But I have a feeling you’ll never get the beach out of an Aussie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Bama. I know for sure that Australian culture would be completely different without the beaches. I don’t know in what way, but I suspect less free.

I knew you’d understand about the beaches. 😁

I have embraced the joys of snow having learned to both x-country and downhill ski, and more recently snowshoeing, but it’s true – you can never get the beach out of an Aussie.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Australia I swam in Lucky Bay, the most beautiful ocean beach I’ve ever had the pleasure to be on. We had it completely to ourselves that afternoon. Heaven! I felt Lucky indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my goodness! Lucky Bay is stunning. I’ve been to WA, but not to Lucky Bay. Just from looking at some pics online I can see why you thought it was heaven.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, Alison – your words and photos alike sing with joy and there’s such a sense of carefree abandon. I loved the broader paean to Aussie beach culture, what it says about the nation as a whole, and your own memories formed at the beach and at water holes in the outback. Even so, it’s also good that you acknowledge the inherent risks of spending time in the ocean. The more popular beaches in Hong Kong are protected by shark nets, and thankfully we’ve not had a shark attack since 1995 (three swimmers were killed by tiger sharks within a span of just 10 days that summer). And your definition of a proper beach is much the same as mine. Growing up, I’d always assumed that beaches were made of sand, so when I got to Nice on the French Riviera, I was aghast to learn that its world-famous beach was all pebbles!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much James. I have such joyous memories of the beaches in Oz, throughout every stage of my life. And it really is the glue that holds the nation together.

I know they have shark nets at Sydney beaches, like in Hong Kong, and probably at the Perth and Gold Coast ones too – wherever the crowds gather.

I’ve been watching a show called Bondi Rescue of the rescues there during the summer. Some days there are as many as 40,000 people on that beach! I can’t even imagine! And 2,500 rescues every season.

I remember being hugely disappointed by Zlatni Rat beach in Croatia because it’s a pebble beach. Thanks for the warning about Nice!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love being near water – and the ocean, in particular – for exactly the reason you described: it’s so easy to let your cares go and remind yourself how small you are (in a good way) against the majesty of the Earth and the Universe. I spent a summer in Newport, Oregon, a 2 minute walk to the beach, and that was one of the best mental health summers I’ve ever had. 🙂

I had not thought about the beach being the thing that ties Aussies together, but now that you’ve laid it out, it’s obvious and logical. And the pictures remind me of beaches in the UK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was so surprised you mentioned that the Aussie beaches reminded you of UK beaches. I mentioned it to Don and we both laughed. Which is to say our experience of UK beaches is limited. Don grew up in the for north east, and as a kid swam in the North Sea until he turned blue. As for me, being an Aussie, it never occurred to me to go to a beach in England. So anyway, your comment prompted me to take a look, and lo and behold, there are some beautiful beaches in the UK! Who knew?! Now if they could just get the weather right lol.

Your Oregon summer sounds idyllic.

Alison

LikeLike

Between the wilds of Oz and the wilds of the Yukon it sounds like you’ve more than your share of remote time.

It’s no wonder 80% of the Oz population lives near an ocean beach. Much more inviting than a desert, where who knows where the nearest water is. There’s something special about walking along an ocean surf.

Most sharks are not dangerous – any more than any other wild animal. Have the Box Jellyfish become less of a problem?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve done a LOT of remote time. I guess it suits me – or did when I was younger.

Australia’s population is ringed around the coast, especially the east coast. It always was the more habitable part of the continent, so it was a no-brainer really.

I agree most sharks aren’t dangerous, but with the number of people in the sea over summer it’s inevitable there’s been casualties and fatalities, and given the Aussie love of the beach it’s not surprising all precautions are taken so people feel safe.

Don’t know about box jellyfish specifically, but there are a number of species that are problematic. Blue bottles are pretty common but won’t kill you. The further north you go (ie more tropical) the deadlier they get.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love these photos of such joy at the beach! I miss the ocean, waves, beach, living inland like I do these days. A wonderful place, Oz, glad to have visited although not for long enough. So enjoyed this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Ruth. I miss the beach too. It’s chilly winter here and we’re on the other side of the city from the beaches, and anyway Vancouver beaches just can’t compare to those in Oz.

I’m glad you enjoyed the post. It was a really enjoyable one to put together.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The beach does not care about worries ~ I love this. Water, in general, is such a perfect place to cleanse away worries. For me, growing up I always admired the Australians in part because of the typical stereotypes I knew about when I was young: the beach and barbeques 🙂 But it is more than this, as you say, “… the beach is the symbol of freedom and independence.” And no matter where you are in the world, when meeting up with an Aussie, there is this essence of freedom when talking with them. Excellent post, Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m glad you enjoyed my delve into the Aussie psyche. Even though, from age 11, I lived in Canberra and the beach was a 2-hour drive away, the beach culture still seeped in. I, like most Aussies, can hardly imagine taking a holiday there that would not involve a beach. But in part it’s the whole psychological thing about water too – living in Canada some of my best holiday memories here involved being by a lake. And water in Oz can be so scarce, but it’s always available at the coast. It really has influenced the national psyche. The stereotypes you heard of arose from truth, as well as the sense of freedom the beach brings.

Alison

LikeLike

Indeed, I’ve also noticed during my travels in Australia how much the beach, the sea, boats and water sports are an important part of Australian life, especially during the long, sunny summer. These beach photos capture the very essence of this practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lookoom. It’s fun every time to photograph at the beach – there’s always so much going on. The beach is such a huge force in the culture there. Even me who grew up two hours from any beach have somehow absorbed beach culture.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love strolling along beaches. I was never much of beach lying around person. After all, I tan very easily, in fact, too easily. Back in Canada by now?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also love strolling along beaches, and like you don’t like lying around getting as tan. I won’t spend much time at a beach where I can’t sit in the shade.

We’ve been back a while – this all happened this time last year.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person