A couple of stories from my youth:

The first story: One night in October 1970, at about 9pm. I’m with my boyfriend at his student accommodation at the Australian National University on Acton Peninsula in Canberra. Royal Canberra Hospital is also situated on Acton Peninsula, a man-made peninsula that juts out into a man-made lake. I own a small motor bike. We decide we’ll go to the Student Union building for a drink and pile onto my bike, me riding, Robin behind. Canberra, especially inner Canberra, is notoriously poorly lit. It’s a dark night. The streets are all but deserted. A car that should have yielded doesn’t even see me and plows right into us. We both go flying and sustain serious but not life-threatening injuries. The ambulance arrives quickly. But get this. We are a five minute drive from the hospital but the ambulance gets lost in the dark maze of winding streets. The point of this story? The hospital, the only one Canberra had in those days, was difficult to get to. The location was spectacular, but apparently was not chosen with emergency access in mind.

Canberra grows, and eventually gets a shiny new hospital out in Woden, easily accessible by freeways. And another in Belconnen. And thus it’s deemed that Royal Canberra Hospital has served its purpose. The hospital is to be imploded and the land used for a museum.

13th July 1997. The government has billed the implosion as a spectator event, and advertises safe places on the opposite side of the lake for people to watch this rare spectacle. 100,000 people gather, one of the biggest crowds in the history of the city. It all goes horribly wrong. Nine people are injured and a 12 year old girl is killed instantly by flying debris. Chunks of metal and concrete are found 650 meters away.

There’s an inquiry of course. Regulations were not followed, the plan failed to meet the code, etc etc.

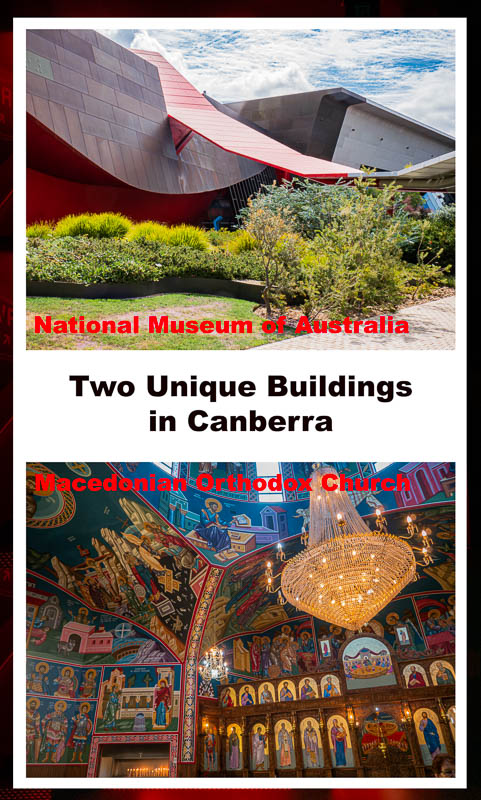

And so it is that Acton Peninsula, with such a tragic history, becomes the location of the shiny new building for the National Museum of Australia.

When we arrive I can see immediately that it is an unusual and interesting building. I am definitely intrigued. But what we come to first is the mirror wall. And is this ever fun!

Long, curving and undulating, patterned pavement and a bulging segmented mirrored wall together creating a continuous game of hide and seek. Each reflection distorted, multiplied, until it’s almost impossible to tell where you’ll show up on the wall, or if, or how many times, or how high. Kids are delighted of course. Parents wait patiently knowing it’s impossible to leave until the children are ready. Even us adults are captivated. What a creation! It’s a funhouse mirror, greatly expanded and out in the open, an unexpected and magical play-land.

To Australia’s Indigenous people Australia is known simply as Country, meaning the land. The first thing you see on the museum’s website is this: The National Museum of Australia acknowledges First Australians and their continued connection to Country, community and culture.

Digging a little further you will find this: As the first Museum in the nation, established in 1827, the Australian Museum is part of Australia’s colonial history and we acknowledge the wrongs done to the First Nations people, the continued custodians of the land on which we stand today. This was and always will be Aboriginal land. The Museum is on the lands of the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples.

It is not a conventional museum. The exhibitions, collections, programs, and research focus on three interrelated themes: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture (50,000 years of indigenous heritage), Australia’s history and society since 1788 (the arrival of British colonists), and the interaction of people with the environment.

And it is most definitely not a conventional building. The architects, Ashton Raggatt McDougall and Peckvonhartel, stated: We liked to think that the story of Australia was not one, but many tangled together. Not an authorized version but a puzzling confluence; not merely the resolution of difference but its wholehearted embrace.

We walk past the mirror to the entrance,

and emerge into a vast convoluted space with curving walls, windows and ceilings. Conceptually it is a huge knot as seen from the inside, a knot tying all the strands of the nation together from the original inhabitants to the British colonists, to the waves of modern immigration over the past several decades, a weaving together of all the stories of Australia and Australians. In this vast space I would not for a second have thought myself in the centre of a huge knot, but kudos to the architects for the concept – and the remarkably unique building that resulted from it.

It is a layered and complex design. Beyond this huge entrance hall we walk through a mirrored forest that is at once unexpected and breathtaking.

Beyond that we come to a movie, both iconic and dreamy; we are shown in one scene after another what makes Australia Australia, from the cities to the small towns to the Outback, from the beaches to the harsh central desert.

As we move on we find that at every turn this building charms, intrigues, and delights us with its flair and originality, both indoors and out.

Honestly we’re not that interested in the collections, though I’m momentarily attracted by this array of vintage Australiana.

We make our way along a curved path past another funhouse of mirrors! How many Don’s are there?

From here we arrive at the central courtyard known as the Garden of Australian Dreams. It’s a misnomer really since it’s not a garden at all in the conventional sense, but a vast undulating symbolic landscape; a stylised map of the country,

surrounded by water,

and where each step represents about 100 kilometres.

‘home’ is repeated in 100 different languages. The lines that crisscross the map include surveyors’ reference marks, road maps, the dingo fence, and Indigenous nation and language boundaries.

Don plays in the “dream home”,

a child plays on the ramp,

and another sits munching a sandwich by the Simpson Desert.

This courtyard “garden” symbolises perfectly the stark reality of an arid, treeless country with a narrow strip of green at the edge. At one end is a small grassy area, where a family rests by the 1950’s inspired coffee caravan, in typical canvas sling chairs, with the inevitable pool typical of the outdoor life of most Australians.

And yet for all this, the garden is best summed up for me by Anna Chauvel, writing in Landscape Australia: Some of the most enduring images of the GOAD are of children playing and wading through the ponds, clambering over carefully curated and placed dead trees and running over the concrete. Today, such behaviour is not tolerated. Engaging with the courtyard while having fun is no longer possible. Visitors to GOAD unquestioningly adhere to numerous “Don’t do x” signs that have miraculously materialized. In attempting to guard against harm, the museum has eliminated all sense of adventure and play – as well as the opportunity for people to connect with the garden and its narrative.

When Julie says: let’s go to the Garden of Australian Dreams, I’m expecting so much more, well at least a garden anyway. I think if people were allowed to engage with it, it would come alive. As it is, it’s a mildly interesting dead zone. Having said that, every other part of the building intrigues and captivates me; I think it’s truly fabulous – in both concept, originality, and execution. At every turn it’s the opposite of boring.

*************************

The second story: It’s never open!

It was begun in 1983. We drive past it frequently because it’s between the homes of my parents and both my sisters. What is this strange building? It’s puzzling, but not enough to make us stop and enquire. In May of 1984 I move to Canada, though over the ensuing years I’m back in Canberra several times. The building is always unfinished. Progress seems at best slow, at worst interminable. For years it seems there’s no progress at all. It’s a bit of an eyesore really; we assume they’ve run out of money. Finally in 1988 the building is completed, though the grounds are not much more than gravel, and the fence, if I recall correctly, is still industrial chainlink.

With time though things improve. Fencing. Landscaping (well lawn anyway). The trees grow. A sign appears out front in both Macedonian (Cyrillic) and English: Macedonian Orthodox Church St. Kliment of Ohrid. There are Macedonians in Canberra? Who knew? Though I don’t know why it should surprise me. At my high school there were students from 29 different countries.

Today this mystery building, designed by Macedonian Australian Vlase Nikoleski, looks like this:

Between 2002 and 2023 I go back to Canberra seven times. I drive past this building dozens of times. I walk past it dozens of times. It’s never open! Not even on a Sunday. I so badly want to see inside.

And then it happens! One day last January Don and I walk past it on the way back from our almost daily hike up Red Hill. It’s open!

I walk in and my jaw drops. I am surrounded by such a joyous bright beauty that it takes my breath away. It is so much more than I could have imagined. It could have been quite plain. I could have done a little shrug and thought oh well, at least I’ve seen it now. Instead what I find is something glorious. Never mind that the images are religious and I’m not, I cannot help but be uplifted by the unrestrained colour, by the sheer exuberance of it.

Macedonian iconographers Vaska and Tony Churkovski, with help from the local community, took two years to paint the wall-to-wall-to-ceiling fresco. It was completed in 2017.

We’ve arrived at the very end of a christening; Bulgarian actually, since they don’t have their own church.

And as the congregation leaves I have time to explore, and to talk with people, and to rejoice in the beauty.

I finally got to see this gorgeous place. It’s so much more than I expected, and definitely worth the wait.

Next post: The Jerrabomberra Wetlands, the Australian National Botanic Gardens, and Old Parliament House. Or maybe family gatherings. Or Sylvie the greyhound.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2023.

What an enjoyable and fascinating post. I am one of those Australians who have remained in total ignorance of these 2 buildings. Partly because I live in Victoria and spent my early adulthood travelling and working overseas, way after my state and interstate travel to the west and north of the country in the early 1970s.

Both buildings are stunning in so many different ways. The visual impact is both creative and colourful.

Thank you for sharing. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Vicki, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

I had no idea you’re an Aussie! I was actually born in Melbourne and lived there until my family moved to Canberra when I was 11. As a young adult I’ve also lived in Sydney, Perth, Dampier, and Tom Price. And travelled in Qld and NT.

Sounds like we’ve both seen quite a lot of the country.

I definitely have a soft spot for Canberra though.

Alison

LikeLike

I love the museum. One of our daughters worked there for many years. Have never been into the church. On the list now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh with a daughter working at the museum I imagine you’ve seen a lot of it! Next visit back I want to explore it more.

The church blew me away! I think it was a Sunday that we got to see inside. Perhaps if you get there earlyish on a Sunday morning it will be open. They also have FB page – perhaps you could enquire there. https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100081577855659

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the link.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW Alison. Thank you for this Magical Mystery Tour of Wonderland. Your photos are so beautiful and surprising. Canberra is delightful. All my best to you and Don.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS- My grandfather was from Bulgaria. I love the reimagining of “The Church of the Spilled Blood,” which is the most beautiful church I have ever been in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Cindy. It was definitely a magical mystery tour. I’d only seen the museum from a distance, and not been inside either building. Neither of them disappointed.

I admit I have a soft spot for Canberra; it’s perennially underrated.

Of course I had no idea of your Bulgarian heritage. Your country, and both of mine, are nations of immigrants – what a wonderful melange that creates.

I googled “The Church of the Spilled Blood” – speechless! So incredibly beautiful. I hope to see it one day!

Alison

LikeLike

how beautiful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. I loved both buildings. So glad we went to the museum, and that I finally got to see inside the church.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

That church is something else. How fortunate it was finally open for you to investigate. We have an Orthodox church here in Spain tucked away in an area not too far from us. It always surprises me when we come across it. The museum is amazing as well and I could see myself spending a lot of time in it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was truly amazed by the church; I honestly had no idea. And I do love the serendipity of having to wait. I think I’d have been sorely disappointed if I’d seen inside before the frescoes were done.

Next time I’m back I plan to spend a lot more time in the museum; I really only saw the building.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s so much going on in that church that it’s hard to know where to look because all of it is my favorite – bold colors, rich detail. I like the outside, too! Funky and different. That’s my favorite pic from this post.

I’m looking forward to the botanic gardens in a future post. 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree about the church – all of it is my favourite! When you walk in the door the whole space just envelops you like a party.

Gardens coming up but I might do some family outings with the Sylvie the greyhound next. Maybe. Haven’t totally decided yet.

Alison

LikeLike

What a great read, Alison. Love your ‘voice’ in this. The first building looks like a Frank Gehry with colours… but there’s another influence there that I can’t nail down. Love from Limoux, Sud de France. K

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Keith. I did initially wonder about finding my voice for this one – I thought a post about a museum building could be a bit dry and boring so wanted to be able to express how it felt – for both buildings, and my earlier connections to those places. Glad I succeeded.

Frank Gehry is the obvious connection isn’t it. That and the whole Destructivism movement, which I really love. Huge fan of Gehry.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember from my trip to Sydney and Melbourne that the museums I went to were always good. The one in Melbourne even gave me chills, in a good way. It looks like as the nation’s capital, Canberra has its own cool museum, which of course I will check out if I ever make it to this city. So lucky of you that the church was open on your last trip! And as you said, it definitely is not one of those places where we say, oh at least I’ve seen it. But rather, I’m glad I finally see it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s been years since I’ve been to Melbourne, and this recent trip only went to Sydney for a few days to connect with friends – so no museums for me. Really glad I got to see the National museum though – it’s an amazing building, and the church was a real bonus!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The stereotype for museums seems to be “boring, static collections of old stuff, half of which you can’t identify.” Nice to hear (and see) that the Canberra Museum defies this stereotype. And the artwork in the church – wow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This museum certainly broke the mold; it’s most definitely not about “boring static collections” and I wish I’d had time to explore them more, but the building alone made the visit worthwhile.

And the church was a huge bonus. So lucky to finally get to see inside.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Architecture intrigues me, so I’m always fascinated by both traditional types and postmodern ones. It’s a pity though that such thought goes only into “important” buildings: museums, government buildings etc. Would be nice if our everyday apartment complexes and houses could have the same interest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I seem to notice the unusual buildings, and will seek them out if I know about them. I’m fascinated by the unusual ones, the original ones, and of course the beautiful ones. I know what you mean about domestic architecture though. Individual houses sure, but apartment blocks are rarely better than functional. Here’s a few that have a bit of style: https://www.fodors.com/news/photos/these-10-apartment-buildings-around-the-world-are-architectural-marvels

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

ooh…many thanks for the Fodor’s article! It was a feast for my eyes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I so enjoyed the wonderful museum stories and photos, so interactive and exciting, despite the horrific destruction of the hospital. When I visited Australia years ago, I chose to skip Canberra, thinking it was a boring seat of government. Your posts have shown me it’s a vibrant, interesting place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Ruth, I’m glad you enjoyed it. Canberra has long been described as boring, and probably years ago it deserved it, though I never found it so since I grew up there so I knew where all the fun was. But now for sure, Canberra is amazing. It’s definitely grown up over the years and has much to offer.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, what a fantastic place to explore the rich and diverse stories of Australia and its people, Alsion. I am in awe of the stunning architecture of the National Museum of Australia as much as its location on Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin – it’s so bold and imaginative! I love how you enter the gallery through a forest of bunya trees, trunks soaring a good few metres to the ceiling. Thanks for sharing, and have a wonderful day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Aiva, I’m glad you enjoyed discovering these buildings. I too was blown away by the National Museum building; it was so much more than I expected. As was the little church. Really glad I got to see inside finally.

Have a lovely day! 🤗

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a unique museum! The mismatched colorful design reminds me a lot of the Groningen Museum. It’s great to see that they acknowledge the First Australians as the owners of this land. Not many politicians can do that these days.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was really impressed with the museum building. And, yes it does have a similarity to the Groningen Museum – interesting and colourful.

First Nations are acknowledged on all Federal government websites and locations, and there are some wonderful outdoor sculptures with quotes from Aboriginal Elders, so some progress is being made in giving them recognition. There is *much* still to be done, but I see this acknowledgement as at least a step in the right direction.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Orthodox Church is very unusual from the outside, but inside it looks very similar to the orthodox churches we just visited in Romania and Bulgaria with the Byzantine patriarchs on the walls and ceilings. How fun is the new museum! What a great way to get people to explore it. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

I figured the Orthodox church would be like many in Europe. It was based on the one in Ohrid (hence the name). One day I’ll get to explore a few in Europe! They’re so beautiful.

And the museum building just blew me away. I’m always a sucker for the unconventional.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person