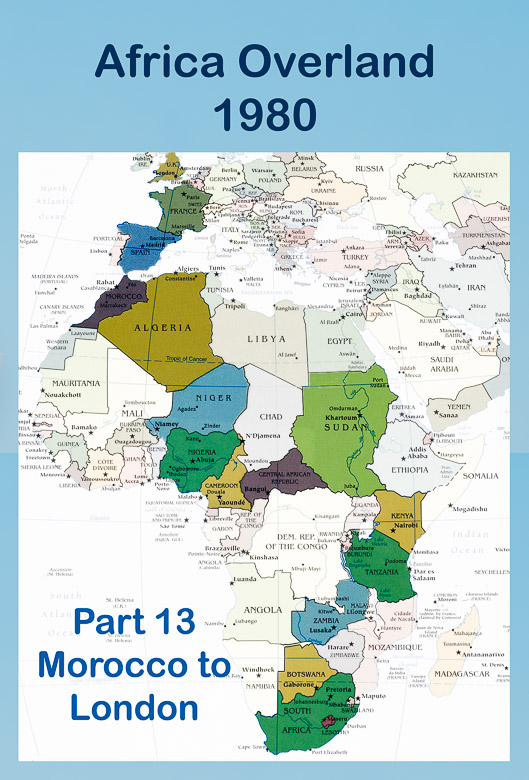

This is the thirteenth, and final instalment of a four-month trans-Africa trip from Johannesburg to London that I did with Exodus Expeditions in 1980, travelling by ex-army truck and camping. We were not sightseeing, though we did see some incredible sights. Our goal was to see and experience Africa from south to north by whatever route was open.

Four months. Twelve people. One truck. Fifteen countries. 18,000 kilometres.

Links to the earlier posts are:

1. The Drums Of Africa. Botswana and Zambia.

2. Tanzania Mania

3. Wildlife And Tribal Life In Kenya

4. The Opposite Of Glamping

5. Turn left At Sudan

6. Mud Luscious and Puddle Wonderful. Central African Republic

7. Becoming Unstuck. Central African Republic

8. Waiting For The Rabbit To Die. Bangui, Central African Republic

9. Between The Jungle And The Desert: Cameroon and Nigeria

10. Sahara Prelude – traversing Niger

11. The Land Of False Borders – the Sahara and Algeria

12. The Marrakesh Express – Morocco

*********************************

I’m leaning out the side of the truck. The awning at the back and sides of the truck is rolled up, and we’re all in there waiting. We’re in the huge Spanish customs and immigration compound in Algeciras. In every direction all I can see are lines and lines of cars and trucks waiting to be cleared for entry into Spain. There are many uniformed border guards with leashed dogs walking up and down the lanes of vehicles; the dogs are trained to sniff out drugs. It all feels a little ominous. My understanding is that anyone trying to import drugs from Morocco to Spain will be sentenced to death. Morocco is such a hash haven, and Spain takes this issue very very seriously. Tangentially, I have a friend who was caught importing Thai weed from Thailand to Australia. He was caught in Thailand and was imprisoned there. It feels like a fate worse than death. Either way it is an extremely stupid and reckless thing to bring hash from Morocco into Spain.

As I lean out the side of the truck idly watching the activity in the compound I spontaneously put my hand in the back pocket of my jeans. Oh shit! Suddenly my heart is in my throat, and my stomach is twisting in knots. My fingers have connected with a small ball of hash in my pocket. Ohshit ohshit ohshit ohshit ohshit! I make a kind of shocked groaning sound. Some of the others look at me. Then I make one of the stupidest decisions of my life. I go to the back of the truck and throw the hash out, but not far. I don’t want to be seen actually throwing something. It lands on the ground a short distance away from the truck, but not far enough to be next to the car behind us.

We wait. Tension descends on us all. Everyone knows what I’ve done. It’s not just about me anymore. My action has put us all in danger. No one says a word. We wait. It is the longest ten minutes of my life. Then suddenly the truck starts moving and we are free, and have officially arrived in Spain. I start breathing again.

One of the others had asked me if I could bring them back a small amount of hash from my date with Abdul in Fès. Abdul has no trouble getting me a big chunk of hash; it’s readily available. Then I find out it is actually illegal in Morocco so I flush it down the toilet, except for a tiny amount, no bigger than my smallest fingernail, just enough for one joint. Back in camp I put my hand in my pocket to give it to the one who’d asked me to get it and I can’t find it. I feel around in there and it seems to be gone. I try over and over and I can’t find it. Next morning I look again and it’s not there. Finally I give up, thinking it must have somehow fallen out. It’s a mystery that I don’t understand, a puzzle that I can’t solve, so I forget about it.

So yeah, bringing some hash from Morocco into Spain was an honest mistake. Throwing it out the back of the truck was just plain stupid. And ever since, I’ve wondered if someone parked right next to it and was falsely accused. Presumably those dogs can detect even the tiniest amount. I profoundly hope not, but wishing I could undo what I have done will not make it so.

From Marrakesh we had driven north to Ceuta, an autonomous city administered by Spain and surrounded by a double fence with barbed wire. It is here that we board the ferry to Algeciras. We are about to finally leave Africa. Our journey is not quite over, but traversing the length of Africa is; we’ve come to the north coast of the continent.

We still have a week to go to reach London, but for nearly four months the twelve of us have lived together in a truck, wild camping, shopping for and preparing our own meals, and absorbing the sights-sounds-smells, the energy, of the “Dark Continent”. I use this term with some caution. Africa was originally dubbed the “Dark Continent” in 1878 by Welsh journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who saw Africa as mysterious and unknown. Certainly it can be legitimately perceived as racist, but I mean it in the simplest sense, to describe a place considered unknown, remote, inaccessible, all of which was true for us. We felt like explorers.

Almost every night, far from towns and villages, we hung out by a campfire, talking, laughing, sometimes silent, watching the flames dancing, and the red-orange coals glowing, until finally we’d retire into sleeping bags in tents to fall asleep to the night sounds of the savanna or the jungle or the wind of the desert.

Campfire Conversation

You said: “I’m glad I know that this time Haley’s Comet

won’t crash into the earth. That’s progress. That’s good. ”

Then you said: “And I’m glad that the United States

had the power to obliterate Vietnam

but still didn’t do it. That’s progress. That’s good.”

And then you said: “And I’m glad we have

the knowledge and the time and the ability to sit

and discuss these things. That’s progress too.”

And when I dared to question

the value of this progress you said

I might just as well worship the sun.

You said: “Go back to sun worship

and live in ignorance,”

“and if the moon should eclipse the sun

you’ll panic,”

“you’ll think the world has come to an end.

You’ll be terrified.”

“Go back to sun worship

if that’s what you want.”

Well I say you have progressed

to worshipping progress,

and if the moon should eclipse

your precious progress

you’ll panic too,

just the same.

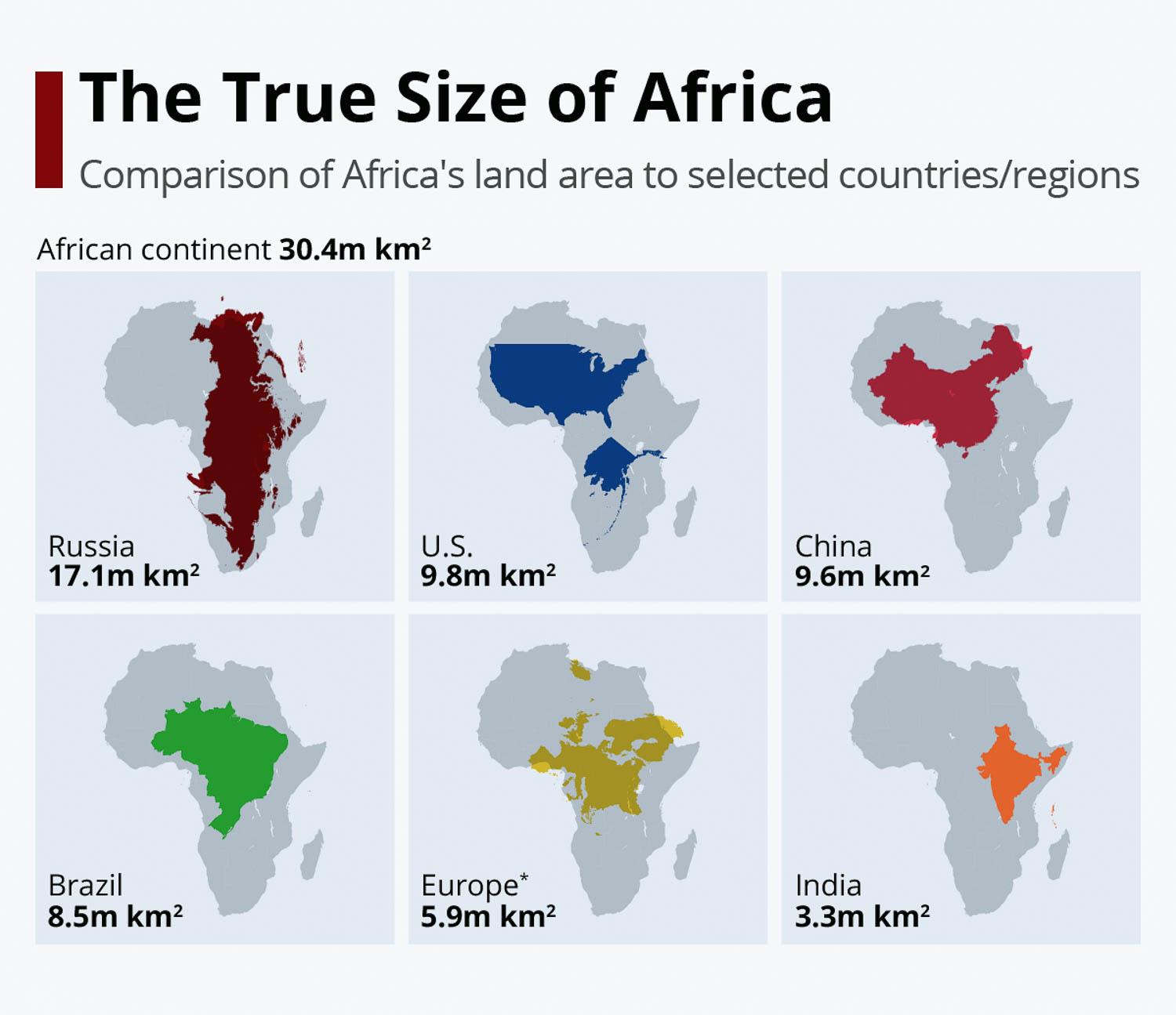

In the beginning, among the information we’re given about the expedition there’s this little gem that really says everything: It is essential to be mentally prepared for an African expedition, and part of that preparation consists of the realisation that once out in the depths of Africa there is no such thing as an itinerary or a schedule. There is only an objective – to get to your destination by whatever route is open. Africa takes no prisoners. It throws down the gauntlet over and over. When contemplating traversing the length of it, just the sheer size is daunting.

But in a way we were too ignorant to be daunted. Two years earlier I’d done a four-month overland trip through South America from Columbia south to Tierra del Fuego and then north to Rio. It was a similar set-up – a group of people living in a truck, wild camping, preparing our own meals. But in South America there were half a dozen copies of The South American Handbook free-floating amongst us. Imagine a book 1.5 inches thick with tiny print on tissue-thin paper. This book was packed with every detail you could possibly imagine of every village, town, and city in every country of the continent, including places to stay, places to eat, transportation, what to see and do. And we all spent time looking through it, and so to some extent charted our own course.

In Africa there was no such thing. Except for Craig, our knowledgeable and competent leader, we were travelling blind. There were no guide books (at least none that any of us had with us), no internet, no google for searching, no socials for networking, no way to contact home, no GPS, little possibility to learn anything about where we were, or who or what we were seeing. And very few books had any information about overlanding in Africa. We could only look in wide-eyed wonder, and grasp onto the small crumbs of information scattered amongst us, or that came from Craig or brief encounters with locals. This meant that much of the journey was indeed the journey itself, the challenge of getting there. And Africa was, and still is, a huge challenge. Except for expedition leader Craig, and to a lesser extent co-driver Brett, Africa was a significant slog into the unknown. Frequently infrastructure, fresh food, and general supplies were minimal or non-existent. There was just us, our leaders, the truck, and the open road. Thousands upon thousands of kilometres of it.

We lived in our own little bubble, and Craig’s knowledge was rightfully focused on technical details – the best route, national border requirements (ranging from visas to a border staffed by convicts), truck maintenance, where to get fuel and water, where to find a bank for currency exchange. He had a wealth of knowledge of the logistics required simply to get us there, and an enormous responsibility.

To some extent the inward focus created by our bubble, and the deadline to reach London, did limit our possibility to engage with our surroundings, but the goal in itself was crossing the length of the African continent, and it gave us all a massive sense of achievement. We travelled the “Heart of Darkness” through central Africa, we faced almost impassable roads of mud, being bogged for ten hours, the shifting sand dunes of the desert as we crossed the trackless Sahara, being dirty most of the time, the fear of bilharzia, the threat of baboons on the truck, and an elephant contemplating charging. We built a bridge across a river swollen by the rainy season, we dealt with food poisoning, with mosquitoes and other bugs, and thieves in the night – twice. And with each other. It was a lot.

And yet, and yet . . . . .

In so many places children ran waving, screaming, laughing after the truck; people were curious and helpful and friendly; the markets fascinating; the landscape immensely varied and interesting, at times challenging, at times breathtaking; the wildlife magnificent. Our surroundings were a continual kaleidoscope of the exotic, the unfamiliar, and so were endlessly intoxicating. There was joy in all of this. And there was joy, and bonding, in overcoming the many challenges.

Large sections of the route we travelled are now extremely dangerous; it is no longer safe to travel in several of the countries we went to due to civil war, uprisings, kidnapping, and terrorism (Sudan, Central African Republic, Niger, the Sahara, even Cameroon). On the other hand in the countries that are still safe there is much better infrastructure including a wide range of really nice secure campgrounds. It’s not like it was; in some places it’s worse, in some places it’s better.

Crossing by ferry from Ceuta on the north coast of Morocco to Algeciras on the south coast of Spain we pass the famous British outpost of Gibraltar.

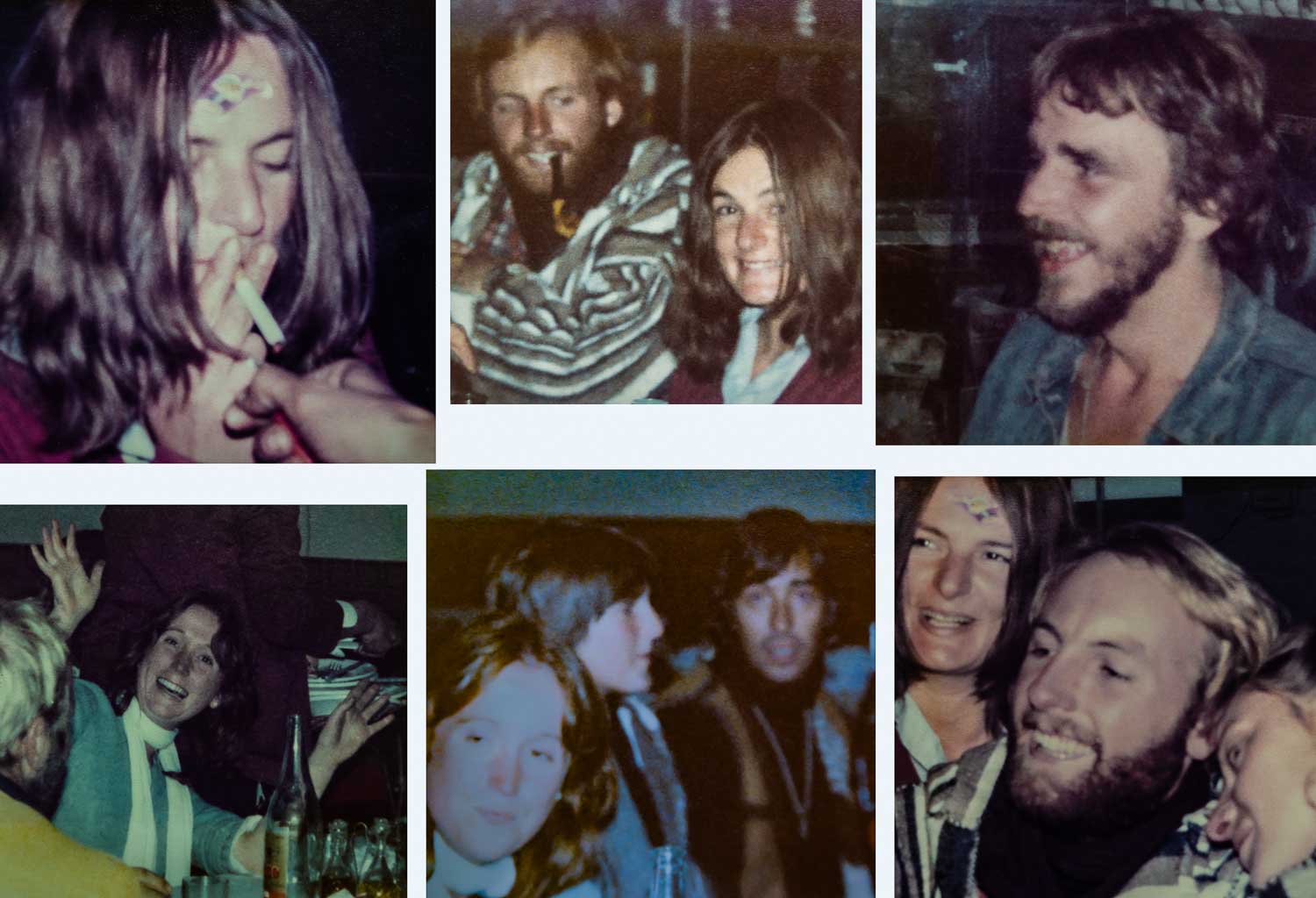

Then we make a mad dash for London. On today’s four-lane freeways it would take three eight-hour days to drive from Algeciras to Calais on the west coast of France. It takes us six days; drive all day, stop with just enough time to set up camp for the night, and do the same the next day. And the next. This mad dash includes a farewell dinner somewhere in small-town, middle-of-the-winter, Spain.

Twelve of us are seated around a long table and overflowing with a monumental relief none of us even knew we needed to feel, or could name. It’s like a volcano has erupted. We are talking over the top of one another, laughing, shouting, cheering. Loud! We are gleeful and exhilarated. We are free! We did it! Food arrives, dish after dish. And the alcohol. There is merriment and drunkenness more than enough to fill a restaurant that, given that it’s December should not even really be open. We are the only ones there.

This meal, this gathering, this celebration, continues for hours. We eat a lot. We drink even more. By the end most of us are very very drunk. There is an argument over the bill. Perhaps they’re trying to over-charge us. Perhaps we are too drunk to understand – not enough Spanish, not enough functioning brain cells. Finally it is settled and we stagger to the nearby campground and collapse into our tents.

Next morning we continue our mad dash to London, eating up the kilometres to Calais.

During the last month of the trip Eric and Dawn have started to get a bit sweet on each other. Eric has plans to wine and dine her in grand style as soon as they reach London. He is smitten.

In Calais we board the ferry for Dover. On the ferry Eric and I talk about British immigration. He says he’s going to tell them he’ll be looking for a job. I’m horrified! Eric, you can’t! You’re not allowed to work in Britain. He won’t listen to me. He thinks that because Australia is part of the Commonwealth he can just waltz into England and live there. He’s determined that he’s right, that he needs to demonstrate he won’t be a burden on British society, that he will work and pay his taxes.

Of course he’s refused entry. My enduring final image is of him in tears as he is sent on the ferry back to France.

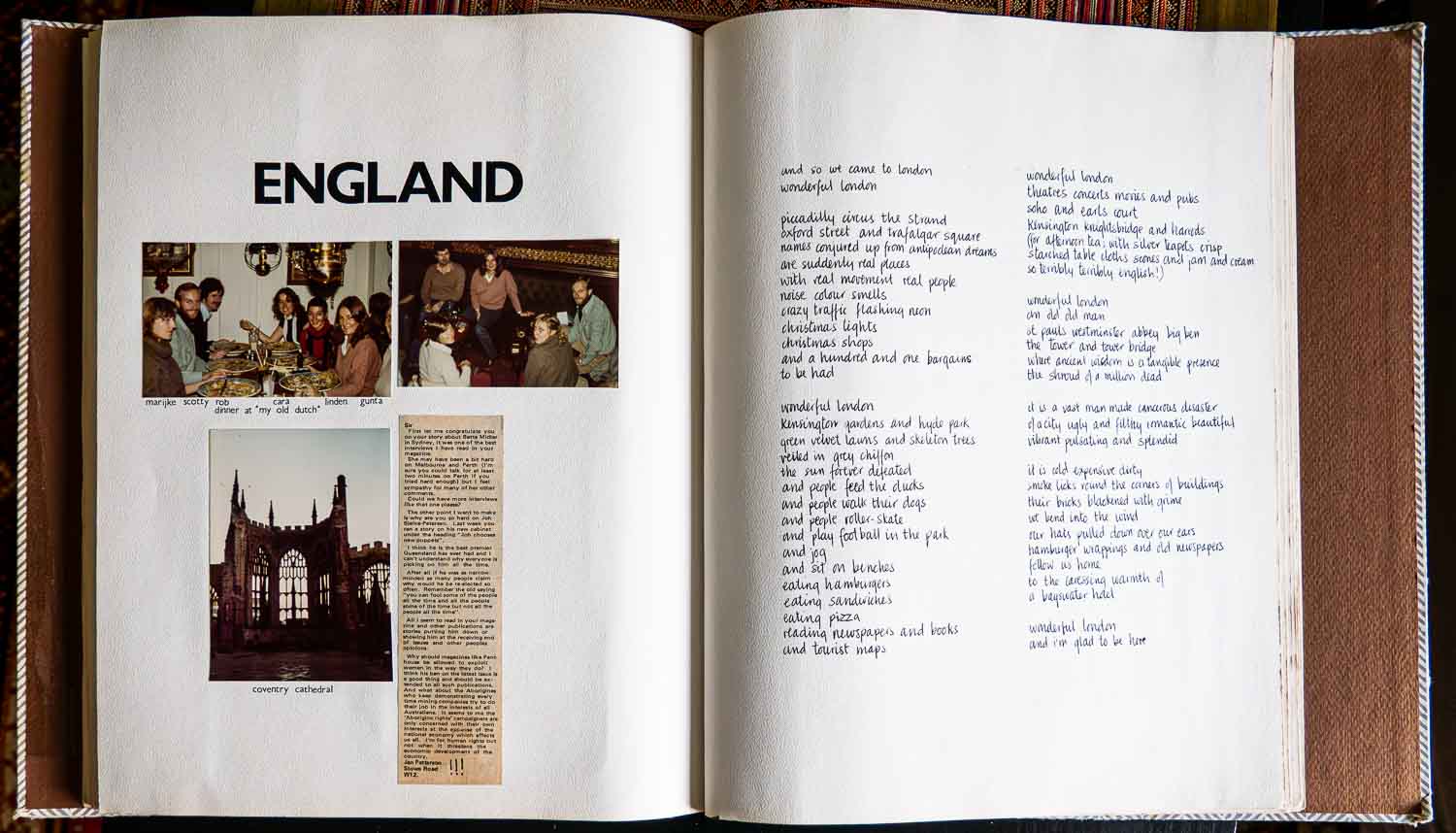

Several of us meet again in London, all scrubbed clean now, at a Dutch restaurant for dinner,

and then afterwards at the local pub.

Finally it is over. Sadly I never see any of them again. I have a couple of leads. I feel that if I can just find one of them it will be a thread I can pull, and the unravelling will reveal more of them.

*********************************

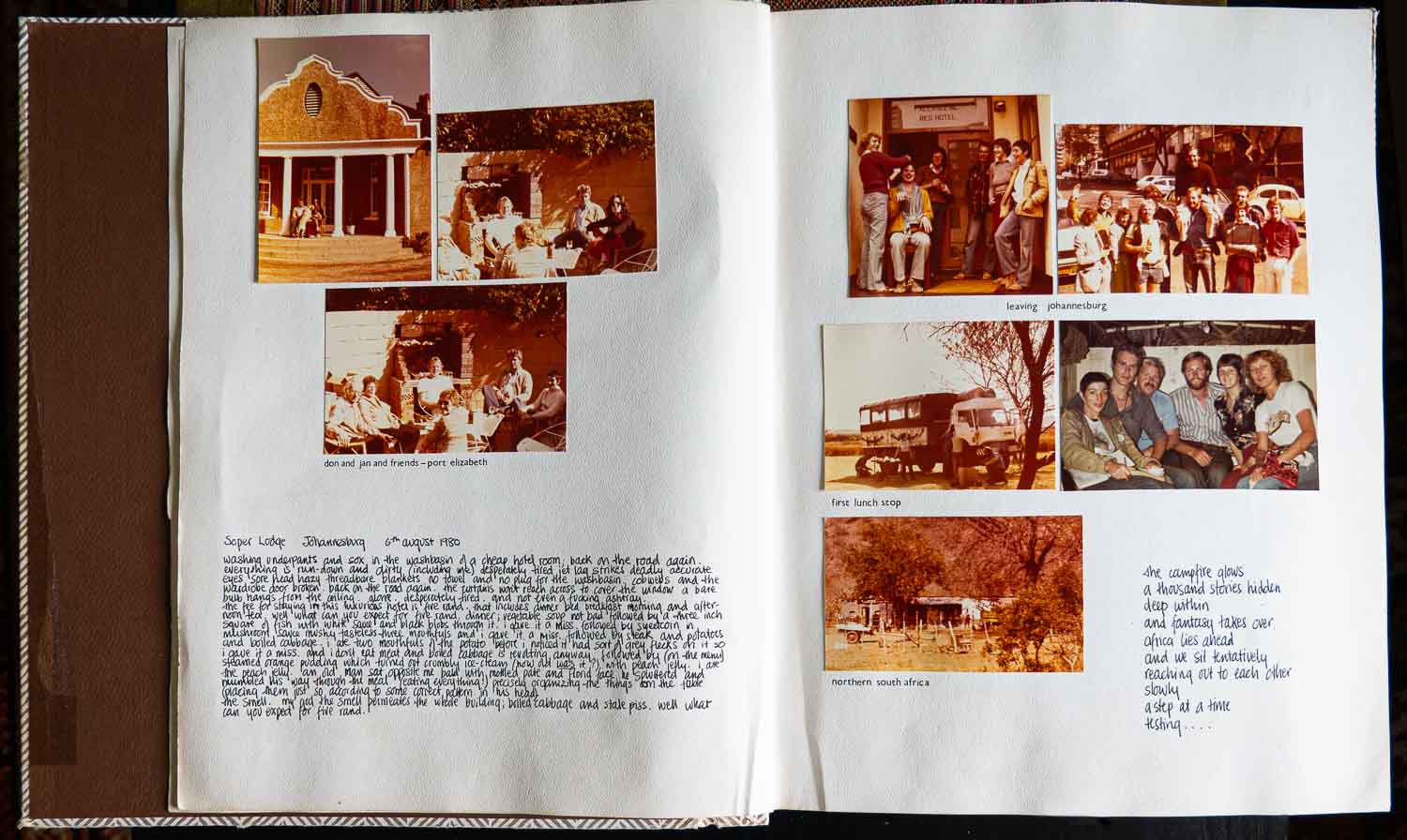

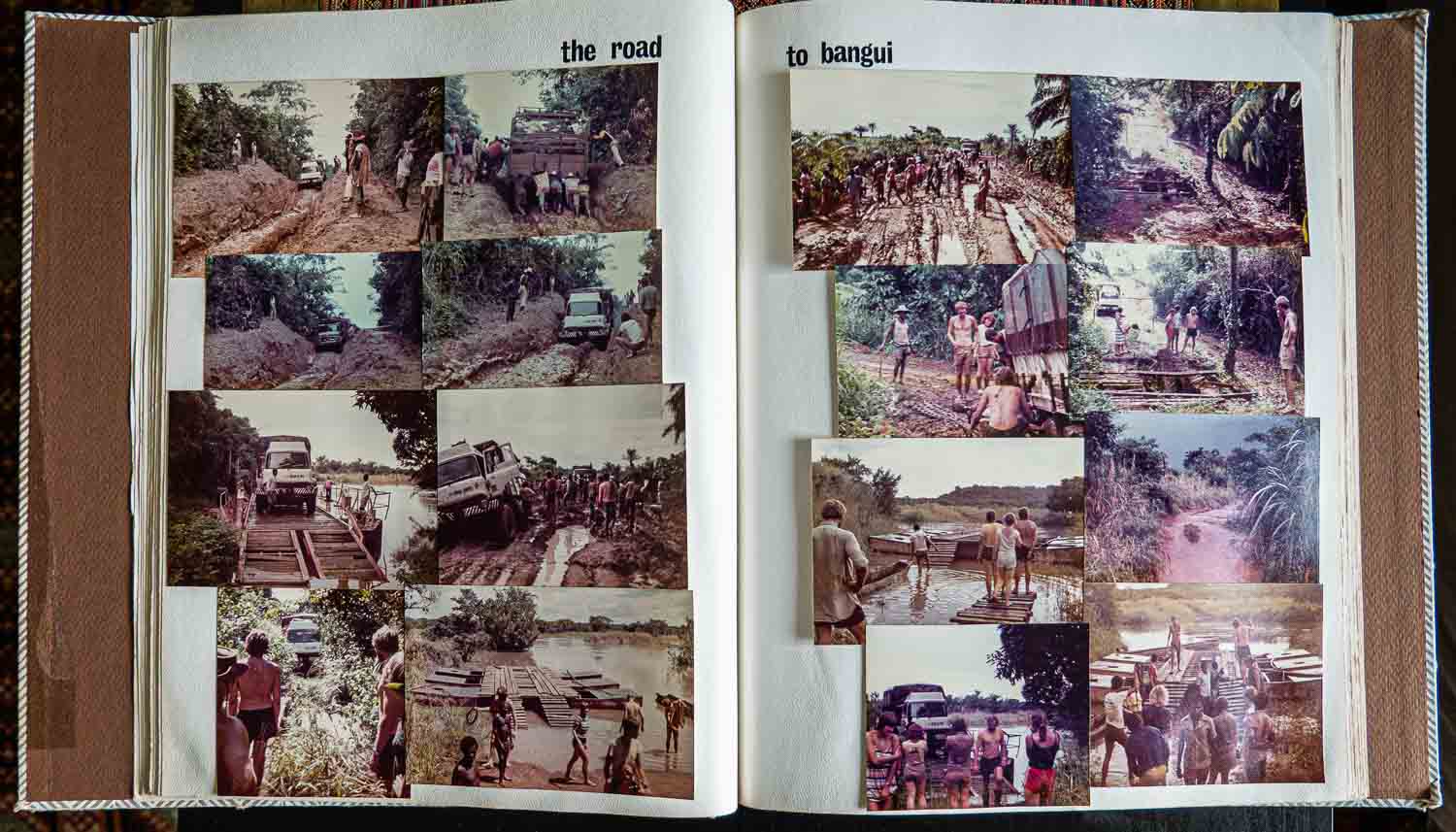

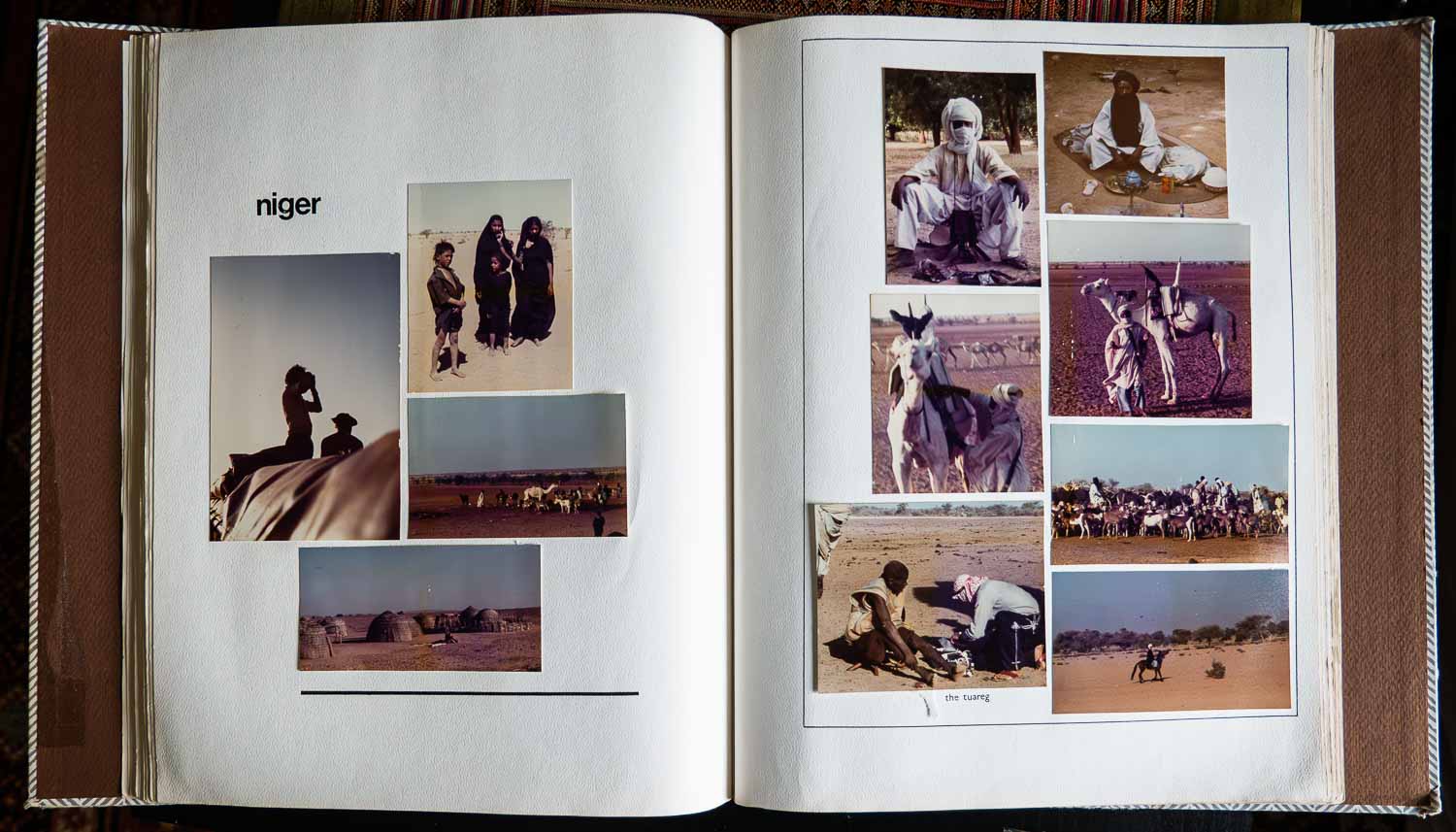

I wrote quite a lot for the first month of the trip, then stopped. The stories come in part from current research, but mainly from memories, and the giant scrapbook I made of the journey, 14.5 x 12.5 inches, and 1.5 inches thick (36.5cm x 32cm x 4cm).

About the photos: They’re pre-digital film photos from a point-and-shoot camera, over 40 years old, and printed with a matt finish. Most are badly faded and discoloured. I photographed them, uploaded them into Lightroom, and restored them as best I could. A couple of before and after examples:

I travelled with Exodus Expeditions, a company founded in 1974 by John Gillies, a Philosophy graduate, and David Burlinson, an Engineer. Their first commercial trip took place that summer to Afghanistan. Their first trans-continental departure, from London to Kathmandu, was in 1975. Expansion into Africa and South America followed. Overland travel was based around multi-week camping journeys, using converted army trucks, with only rough schedules and limited budgets. They benefited from the open-borders of the 70s and 80s, much of which is no longer possible. Trans-Africa from London to Nairobi, Johannesburg, or Cape Town, or the reverse, was a true travel challenge.

Disclosure:

1. I’ve changed the names of everyone involved for privacy.

2. Obviously any photo with me in it was taken by another member of the group, but I’ve no idea who. We all swapped photos when we got to London.

Next post: perhaps I’ll take a short break to ponder my next move. As mentioned I did a similar trip in South America in 1978; maybe I’ll chronicle that next. In the meantime, for a change of pace, I have a bunch of gorgeous flower photos to share.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

Dear Alison

Thank you for your chronicles of this epic voyage. I have been absolutely captivated these past months. This is true exploration. I love the photos in all their faded glory. I have pre digital photos of my trip to Papua New Guinea that I’ve attempted to restore, but they are so murky from age and humidity. We have become spoiled with digital…

I look forward to reading about your South America odyssey too and the flower photos!

Julie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Julie. I’m truly delighted by your comment as I have such a high regard for your own writing. It *was* true exploration. We really had no idea what we were getting ourselves into.

I do love the old photos in the scrap book – it was the creative urge that arose to record the trip at that time – and I also love that I’ve been able to bring them back to life a bit. I was lucky that my photos weren’t affected by humidity. It’s a pity you’re unable to restore your PNG photos. I imaging that was a pretty amazing time. My sister lived there for a while in the late 60s, but I’ve never been. And yes, we have become spoiled with digital. I love it.

Alison

LikeLike

A great series, Alice! Thanks so much for sharing. It truly was an adventure. And, I too, am looking forward to South America.

On the subject of drug busts, when Peggy and I took three years to travel back in 2007, good friends had given us a whole flat of Alice B. Toklas brownies as a kick off. We were driving through southern Arizona when we came on a road block complete with drug sniffing dogs. It was an Oh Shit! moment for sure. Would we have to call our kids to get us out of jail? I had placed the brownies in a low, outside compartment, dog nose level. Each vehicle had to drive slowly past the dogs. I watched in my review mirror as the dog suddenly pulled on its leash and pointed its nose at the compartment. It went on forever in my mind. And then the drug enforcement officer signaled us to keep going. I am not a praying person, but I sent a little thank you winging skyward. Five miles later we found a safe location to dispose of the brownies. What a waste, but…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Curt. I have loved reliving this epic journey.

I guess now I’ve mentioned South America I’d better get on it, though I’m also inclined to write about my years in the hunting camps up north. Both eventually I’m sure.

Oh the road block with the brownies! Definitely an Oh Shit! moment. And the dog straining on the leash as you drove past! Heart in mouth! I’d have sent a prayer of thanks up too.

A sad waste of good brownies 😢

Alison

LikeLike

I bet. How could you not. And I am equally ready for either “Tales of the Far North” or “A Journey through South America.”

Peggy and I are digitizing old photo albums, also reliving our past! Even without brownies, facing a group of armed men with dogs ban be a daunting task!

LikeLiked by 1 person

From your point of view, How is Africa a “Dark continent”?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll just copy here what I’ve added to the text above. I deeply apologize if you found it offensive, and now having done a little research, I can understand why you would. This is what I’ve added to the text above: I use this term (Dark Continent) with some caution. Africa was originally dubbed the “Dark Continent” in 1878 by Welsh journalist and explorer Henry Morton Stanley, who saw Africa as mysterious and unknown. Certainly it can be legitimately perceived as racist, but I mean it in the simplest sense, to describe a place considered unknown, remote, inaccessible, all of which was true for us. We felt like explorers.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t find it offensive. I only wanted know your Point of view.

How’re you doing?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so pleased to hear you didn’t find it offensive. It’s the last thing I would have wanted. Except for our expedition leader (who had been leading these groups for four years), we were all pretty ignorant about Africa so it very much was a journey into the unknown – hence the “dark continent”. I’m ashamed to say that all I knew about Africa back then was your skin colour was different, there’s some astonishing wildlife, the Sahara, and the names of most of the countries. My only regret is that I didn’t have more time to get to know more about the different peoples and cultures.

I’m doing great. Hope you are too. Maybe one day I’ll get back to Africa!

Alison

LikeLike

It’s been a fabulous series. Thanks for taking me back to Africa. I was on the edge of my seat reading about your hash border crossing. Gulp.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Peggy. I knew you would relate. Oh the hash at the border was definitely a moment! I could hardly believe it when we started moving forward and were out of there. Lucky!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

An adventure extraordinary…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was! Thanks for coming along.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed this series very much Alison. What an excellent adventure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Cindy; I’m glad you enjoyed it. It was such an amazing adventure I can hardly believe I did it!

Alison

LikeLike

An amazing adventure. I have enjoyed every episode. Your brought these memories to life. How wonderful that you made a scrapbook too. Thanks for taking us along. xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Darlene. It was such an enjoyable creative process for me to relive this journey. It gave me life for a while, and gave life to the memories. I almost trashed that scrapbook many years ago, but couldn’t quite bring myself to destroy all that work. I’m so glad I kept it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is always a reason why we save things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was such a great story to read. What an adventure you had, thank you so much for sharing it. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Maggie. It was such a great tale, just begging to be told really. For quite a while I thought that when I wasn’t travelling I would write about the travels of my youth. It’s a fun process. And even more fun to share it. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

An absolutely epic adventure, Alison. Wow ~ four-month trans-Africa trip is something I could only dream about, and what a joy it is to be able to experience this through your posts. I’m looking forward to catching up on your earlier writings. The scene you painted with the small ball of hashish at the border is brilliant – how I’d love to have tagged along with this adventure of yours.

The old photos do perfect justice to living such a life, and your conversations show how vital companionship is in forming who we are and who we become. Being somewhere where the gauntlet is thrown down continually creates not only memories but the fortitude to work through it all forges who you are. Beautiful. Your writing in just this post is inspirational… 😊.

I try to imagine what the scene was at the final party/dinner/pub: “We are talking over the top of one another, laughing, shouting, cheering. Loud! We are gleeful and exhilarated. We are free! We did it!” It must have been such a wonderful feeling, not overwhelming – but simply pure ecstasy. Damn, I feel young again reading this! Cheers to beautiful memories and to making more memories ~ whether it is writing and telling stories or jetting off again 😎.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Dalo for all your kind words. The whole epic adventure was something I can hardly believe I did, though at the time we were all just there doing what we’d signed up for – without even really understanding what we’d sign up for.

It’s been an amazing process for me to bring the photos and memories to life, fun and rewarding, a second sense of achievement 40+ years after the first.

Oh the hash at the border! That was definitely a moment! I’m glad to hear I managed to convey that.

The whole experience, dealing with the circumstances, and with the others, certainly affected me in ways I never even really understood at the time – fortitude, as you say, and resilience, and an affirmation of my love of the edge that adventure brings to life; that I have never lost.

Smiling at you saying our wild farewell dinner makes you feel young again! Me too!.

There’ll be no jetting off for now, but I have many more stories of the travels of my youth to share.

Alison

LikeLike

What a trip! Good thing nothing happened to Craig – pretty amazing to think you were so reliant on just one person.

Good job with the images in Lightroom, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Snow. Restoring the photos was a challenge for sure. Some were just impossible, at least with my level of knowledge, but a fun process anyway.

Yes, very good thing nothing happened to Craig! Brett would have stepped up, but for sure he didn’t have Craig’s level of experience or knowledge. It’s possible the company would have flown someone in if necessary. Anyway thank goodness that wasn’t necessary.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, that was epic. And the hook for this piece – yikes!

Do you ever wonder, with all the adventures you’ve had, what the mindset is for folks that have rarely gone further than 100 miles? It seems like it’d be a different universe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Dave. It really *was* epic. Looking back I can hardly believe I did it.

The hash at the border! Yikes is right! One of the moments in life that I will *never* forget.

I’m puzzled by people who do not want to see the world, well people who obviously have the means, or even just their own country. I guess some people are just not moved that way but I do think it means they become ossified in their thinking and beliefs. I’ll never forget meeting a woman who lived in Yorkshire, a relative of my then boyfriend. She was 20something, working, well spoken, and she’d never been to London – a 4 hour train ride away. It truly puzzled me.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh no! Our grand tour is over? Well nuts!If you’re comfortable, I’m curious about you saying you never saw them again. Is this one of those pre-digital era things were it took concerted effort to stay in touch by mail? (I have several friends from pre-internet that I wish I had met when FB was around so we could stay in touch).

In some ways, reconnecting with these folks would be much more memorable than the traditional high school or college reunion (neither of which I have participated in).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, sadly it’s finally over. I’ve had so much fun with this project. It’s been really rewarding.

Never seeing them again was definitely a pre-digital thing. We all exchanged addresses and phone numbers, and Lynne who I was closest with, was a fellow Aussie. I was not a good letter writer except to my parents, and it was another 12 months after this before I got back to Oz. At that time I tried to contact her but I was unable to and so she must have moved on. Worst thing is I don’t remember anyone’s last name – except one. I’ve sent an email to HR at the company I believe she may work for but have heard nothing back. Time to give them another nudge.

I’d love to reconnect with them – well lol, most of them. Cameron not so much probably 😁

Alison

LikeLike

You never know – Cameron may have mellowed! 😛

In all seriousness, though, it would be fund to reconnect with quite a few of the folks on this trip. I hope you’re able to connect them!

If you have any other epic cross-country journeys like this in your life history, it would be fun to go on another adventure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did a very similar thing in South Africa in 1978. Think I’ll write about that next.

LikeLike

Oooh, South Africa! Yes, please. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops, I made a mistake. I meant South America!

LikeLike

I could feel the tension when everyone was waiting for the border check to finish. I’m glad you could make it safely to Spain! I love the scrapbook. Do people still make them today? It’s something that should survive the digital age, in my opinion. There’s something special about turning over its pages compared to scrolling down a webpage. What a journey you had, Alison! And thank you for sharing it with us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh that border crossing must be one of the scariest moments of my life! It could have turned out to be really traumatic for all of us. The way it went makes me feel really really lucky and as if something is watching over me, over all of us.

I’m so glad I kept the scrap book. At the time it was such a wonderful creative project putting it together. And yes people definitely still do scrapbooking today; I think it’s quite a big industry. And I agree – so much more sensual and creative than scrolling.

It was a truly amazing journey. Thanks for coming along Bama.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful series. It was great to “travel” through your eyes and ideas, time travel of a sort, too.

That type of travel is a great way to bust open a world view.

Thank you for posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m so glad you enjoyed coming along on the journey. There are many other factors, but if only because of the internet such a journey is no longer possible. And yes, a great way to bust open a world view.

It has been a true pleasure to put this series together.

Alison

LikeLike

Awesome achievement, and the telling of, Alison. Like Bama, I could feel the tension of the drugs incident. It seems such a shame not to have contact with any of these people now, but your lives will have gone in so many different directions. So sorry for Eric!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Jo. It has been a wonderful creative journey putting these posts together. Oh the hash at the border! I’m glad I could convey the tension of that. I’m still freaked out just thinking of it.

I wish I could connect with any of them. I need to follow up on that lead I have.

I felt for Eric too. And of course in those days there was no internet so he couldn’t check my information, though I’m sure it taught him a good lesson for future travel.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Alison. Such a wonderful insight to overland travel in the ’80s, it brings back so many memories of the time.

I may have mentioned previously somewhere, that the slides of my Exodus Kathmandu-to-London trip in 1985 got accidentally thrown away by my mother during a house move. Gutted, I would love to look back on them now, c’est la vie!

Take care, keep travelling while you can. I look forward to reading of your next adventures!

Dave.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Dave. I kind of got to do the trip all over again 40+ years later, though I do wish I could have remembered more, or written more at the time.

Losing your slides! I’d have been gutted too! Have you forgiven your mother yet ? 😁

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I so enjoyed this whole series, Alison! Your scrapbook looks very similar to MANY that I still have of my own early travels. I’ve thrown away large piles of old things, but I can’t bear to pitch those old memory books. As I’ve said many times before, reading about this trip gave me a lot of FOMO, and I know something like this would be impossible to pull off nowadays. Thanks for re-documenting this epic journey and sharing it with us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lexie. It’s been such a rewarding project for me. It now amazes me what we did, though at the time we were just doing what was in front of us, having a big adventure.

I’m so glad I still have my scrapbooks. When I moved to Canada in ’84 I got rid of everything, but couldn’t bear to ditch the scrapbooks so left them in an unused loft in my sister’s house. Next trip back I got them. What a history I would have thrown away! I have two more, and I totally get why you still have yours.

You actually could do a trip like this but it would be a combination of wild camping, campgrounds, and the occasional hotel. More comfortable and the trucks are way more luxurious, but still trans-Africa overland. These days the companies don’t go through the centre of Africa as it’s too dangerous. There’s a company called Dragoman that I’ve heard of that looks pretty interesting. And there are others.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I very much enjoyed the wonderful and downright adventurous series of your African overland tour as you crisscrossed the land of awe-inspiring beauty and wilderness and I am sad to see them come to an end.

I think you did a fantastic job in uploading your photos and restoring them. You know some people feel nostalgic and sad looking at old photos. But for others, it can be a source of motivation. It can inspire us to see how far we’ve come, and how much we’ve accomplished. Looking at old photos can remind us of the good times we’ve had.

On a final note – there are so many incredible places to explore in the world and so little time therefore thanks so much for inducing a bit of inspiration into my future travels and for sharing all the incredible landscapes, culture & wildlife I could only imagine. Thanks for sharing, and have a good day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Aiva, I’m glad you enjoyed it all. It was a truly rewarding project for me. Thanks re the photos – some were so bad I couldn’t use them, but most I could at least bring back to a usable state. I never get sad looking at old photos.

I know exactly what you mean about so much world, so little time. There’s still so much of the world I’d love to explore.

Take care

Alison xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

🥰🥰🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s been fascinating to read about your adventure, and I’ve yet to read the first stages, having taken the truck on the way. It’s certain that we can no longer travel in this way for political and security reasons. New technologies and services are also changing the way we travel, it’s hard to say that this isn’t progress. Having experienced both forms of travel is a privileged knowledge that will be increasingly rare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lookoom, I’m glad you’ve enjoyed the journey. It definitely was the trip of a lifetime, and as you say, no longer possible. Even without security reasons, the internet has changed the world, so much of the Africa I experienced no longer exists. I would think it all progress if it had led to some true equity for the African people, but alas as far as I can tell, in many places they are still being exploited as always.

I agree that having experienced both forms of travel is a rare privilege.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do enjoy your travels so much. I would like to get some info from you. I know you used Skyjet when you and Don were travelling. I am thinking about using them for a 2 month trip to Mexico. What was your experience like with them. Would you recommend. Did you ever had to use them

Thanks for any advice

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m glad you’re enjoying my posts. Perhaps you are thinking of Medjet. It’s a global repatriation insurance in case of medical emergency. We always used MedjetAssist and paid for 12 months. I don’t know if you can buy less than that. Here’s a link to their website which should answer all your questions. https://medjetassist.com

BTW we *loved* Mexico and have been several times. Happy travels!

Alison

LikeLike

That must have been such an amazing trip!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really *was*! Definitely one of the highlights of all my travels.

Alison

LikeLike

As bad as it might have been to throw the hash out of the truck, what else could you have done? It would have been more dangerous if found by the authorities. Sometimes it’s those last minute decisions that might determine the rest of our lives – scary!

I have so enjoyed following this journey. So courageous, all of you! If anything had happened to Craig, omg! Thanks so much for sharing your terrors, joys, and wonderful writing to all of us, Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The whole incident with the hash was soooo scary, but you’re right, there’s not much else I could have done. I have an alternate scenario re that tiny ball of hash on the ground – that the next car drove right on top of it and it got stuck in the tire grooves of that car, and when they were cleared to go they drove it right on out of there.

Thanks Ruth, I’m glad you enjoyed my Africa story. And yes, thank goodness nothing happened to Craig. I imagine Brett would have taken over and arranged to have Exodus fly in a new expedition leader to wherever we were. Don’t want to think about it . . . . .

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose those tour companies have back up plans and you would have been taken care of. Loved reading all of this and imagining being in your shoes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ruth xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow!! 5The Last Leg – Morocco To London. Africa overland 1980.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was pretty amazing for sure!

Alison

LikeLike

Incredible story! Your journey through Africa sounds amazing, and I loved reading about your experience. For anyone planning a trip, Regal Travel Agency in Dubai is great for tourist visas. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. Africa overland was one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever done. I hope I get to Dubai one day!

Alison

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing the story. This is such an extraordinary trip that very few people have experienced. Not to mention those precious photo records—the description of what you saw and heard took me to the 1980 Africa . Anna and I have just come back from the travelling in Namibia, we rented a car there and drove around the country for 2 weeks. Everything was modernly equipped, we even had WIFI at the camp site in the Kalahari desert. We enjoyed reading your post a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Kenny. I’m glad you felt a little as if you were there with us on this amazing journey. It was for sure one of the most incredible things I’ve ever done. Lucky you to have spent time in Namibia. I’d love to go there one day. That sounds like a truly fabulous road trip. And for sure it sounds a little different than 1980! 😂

Alison

LikeLike