This is the eleventh instalment of a four-month trans-Africa trip from Johannesburg to London that I did with Exodus Expeditions in 1980, travelling by ex-army truck and camping. We were not sightseeing, though we did see some incredible sights. Our goal was to see and experience Africa from south to north by whatever route was open. Four months. Twelve people. One truck. Fifteen countries. 18,000 kilometres. Links to the earlier posts are listed at the end of this one.

*********************************

Two of the guys are carrying a sand mat, one at each end of it, and are running along one side of the truck. The same is happening on the other side. They’ve picked the mats up the second they were free of the rear tires and are running to quickly get them placed under the front tires before the truck sinks into the sand again. As soon as the mats are free of the front tires the mats are pulled from under the truck and placed under the rear tires. This dance goes on and on, with everyone who’s able taking turns. In this way we make slow progress, sometimes to get going only to be stuck again ten metres later. Not all of the Sahara is like this, this soft deep yielding sand that would stop the truck in its tracks, if there were any tracks, but good long stretches of it are. The sand mats, or traction mats, save us every time. That, and our exertions to keep getting them into place as the truck rolls slowly forward.

. . . . following nearly two decades of kidnappings, much-increased trafficking, rebellions, revolutions as well as the spread of weaponry, independent tourism in the central Sahara has collapsed or is severely restricted. But it wasn’t always like that. The late 1970s and 1980s were a Golden Age for desert tourism: post-colonial nations had yet to be beset by internal strife, while the popularity of the Dakar Rally as well as the emergence of desert-capable motorcycles and 4x4s, saw adventure tourism flourish in the central Sahara. Make no mistake: the good days of roaming free around the Sahara are pretty much over. It was great while it lasted but you could say the Sahara has returned to what it always was: a lawless wilderness into which outsiders venture at their peril. Chris Scott

But in 1980 it was wide open. There were two main routes to travel in a north-south direction through the Sahara. One was via Timbuktu in Mali, and the other via Tamanrasset in Algeria. Craig says to us The only reason to go to Timbuktu is to say you’ve been there. So we head north from Agadez in Niger to Tamanrasset in Algeria, following an age-old caravan route through one of the harshest places on the planet, a sweltering inhospitable furnace. It is known as the Route du Hoggar. Tamanrasset is situated at the southwestern foot of the Hoggar Mountains.

At the border from Niger into Algeria the truck is parked at the side of the road. My heart is in my throat. Probably some of the others feel the same, as I’m not the only one smuggling alcohol into Algeria where it is banned. We wait. All our gear is in the truck. A bottle of scotch is wrapped in clothes and buried deep in my backpack with all the rest of my stuff, in the bottom of my locker, under the seat. All the seats are raised so the border guards can see into the lockers. We stand in a row next to the truck as the guards walk up and down the centre aisle looking around, and into the lockers, but not tearing things apart. Finally they leave and we are free to go. There is a collective sigh of relief. Phew! Even now I can feel the tension of it. What was I thinking?

Shortly after the In Guezzam Border Post we stop in the town of the same name, for fuel and supplies. As soon as we get out of the truck there are men approaching us to buy whatever alcohol we have. I make a tidy profit.

A series of deserts cover almost all of north Africa. At some time in the far colonial past, deals were made and lines drawn on a map, and the result was a group of separate countries all of which are cloaked by these deserts that are collectively known as the Sahara. Algeria, Niger, Sudan, Tunisia, Chad, Libya, Mauritania, Mali, Western Sahara, Egypt. But the desert itself knows no such lines, and for centuries neither did the people, the nomads, the trade caravans that traversed it, versed in the ways of survival in this unforgiving place. The camel caravans followed a string of reliable wells, while circumventing difficult terrain like mountain ranges or sand seas. The caravans ruled. In some places they still do.

Trade and travel within and across the Sahara have existed for much of documented history. In the centre particularly there is a long-standing history of migration and a nomadic lifestyle, and we travel right through it.

We enter the desert just south of Agadez in Niger. The distance from Agadez to Tamanrasset in Algeria, the first oasis we come to, is 870 kilometres. To be clear, there is no road. It can change from very rough to very sandy seemingly on a whim. Sometimes there’s a series of tire tracks to follow, that may or may not have had more sand blown over the top of them. Sometimes it’s firm sand and we roll easily along; even so distances can be deceiving.

Navigation difficulties are very real. The group of tire tracks can be acres wide, a seemingly endless number of choices to follow, but all mainly, hopefully, going in the same direction. When they become sparse we’re on the lookout for the barrels. The barrels are 45 gallon fuel drums filled with sand, spaced every few kilometres along the route. When the way forward seems uncertain we stop to search for them.

Given that there can be days between the oases where we may replenish our water supply it’s essential we remain on the track.

At one point in northern Niger we are uncertain where we are, where the “road” goes next. Suddenly, surprisingly, a Tuareg man arrives from nowhere. A mirage at first, he slowly solidifies and presents himself. He asks if we need help. He points us in the right direction. He asks if any of us would like to accompany him back to his camp. We decline, thinking we’ll never find our way back. Or that we’ll be kidnapped. But oh what a missed opportunity! The Tuareg have been rebelling for decades against the colonial, and post-colonial governments of both Mali and Niger, wanting their own autonomous region, but I believe this man was genuine and meant us no harm.

We never see another vehicle. We are alone in this vast enigmatic wasteland. I’m not afraid of getting lost, though perhaps I should be. I don’t think about the Sahara as a huge un-policed wilderness, though perhaps I should. I seem to live in this place of trust that the world is benign; trust in life, trust in the unfolding of it, and most especially trust in Craig. This is new territory for us, but for Craig it’s familiar, a terrain he has crossed several times previously.

The sand swirling from the movement of the truck, or from the desert wind settles on and in everything. We understand why the Tuareg nomads dress as they do, wrapped from head to foot against the heat and the dust. Eric, riding on top of the truck, devises his own protection.

We camp each night under a sky so bright with stars, so many stars, that one could almost disappear into them. We stop for a quick lunch, or for a cup of tea, burning some of our precious wood to boil the kettle. Afterwards sand is thrown over the fire to put it out. Not noticing, I walk in it and burn the bottom of my foot. Ow ow ow! The quick first-aid from Steve is to put burn cream on it, which I now know is the exact wrong thing. Ice is what’s needed, but of course having ice in the desert is like being able to fly. Most of us are often barefoot here, but I learn the hard way it’s not always such a smart thing to do. Plus the sand can be so hot it’s impossible. On the other hand (ha! or should I say foot!) Brett never wears shoes for the entire trip.

We stop at every oasis – Tamanrasset, El Golea (now El Menia), Ghardaia – for food, groceries, fuel. At each place we collect wood – whatever sticks we can find, much of it the shedding from palm trees. And water of course – there’s enough to drink, but only a precious one-litre-a-day for washing. We wander away from camp, but there’s really no privacy here.

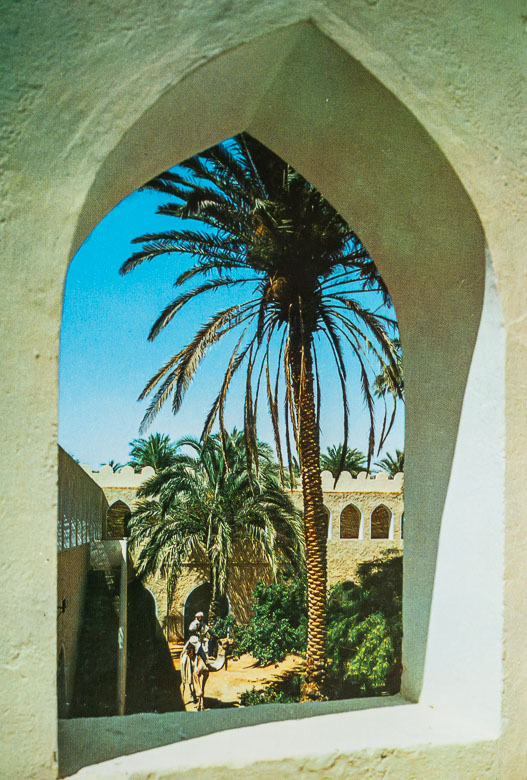

Tamanrasset, lying at the foot of the Hoggar mountains is all mud brick buildings; an ancient town with an interesting combination of military, Arab, Tuareg, and French. It sits almost at the geographic centre of the Sahara, and has long been a stopping point for traders, merchants and travellers. It’s a Tuareg oasis where we find apricots, dates, almonds, figs; a cornucopia! And there is a corrugated-iron hole-in-the-wall, and the man behind the counter has a huge vat of hot oil. He throws dollops of dough into it, and out come, all uneven and misshapen, the best donuts I’ve ever eaten, bar none!

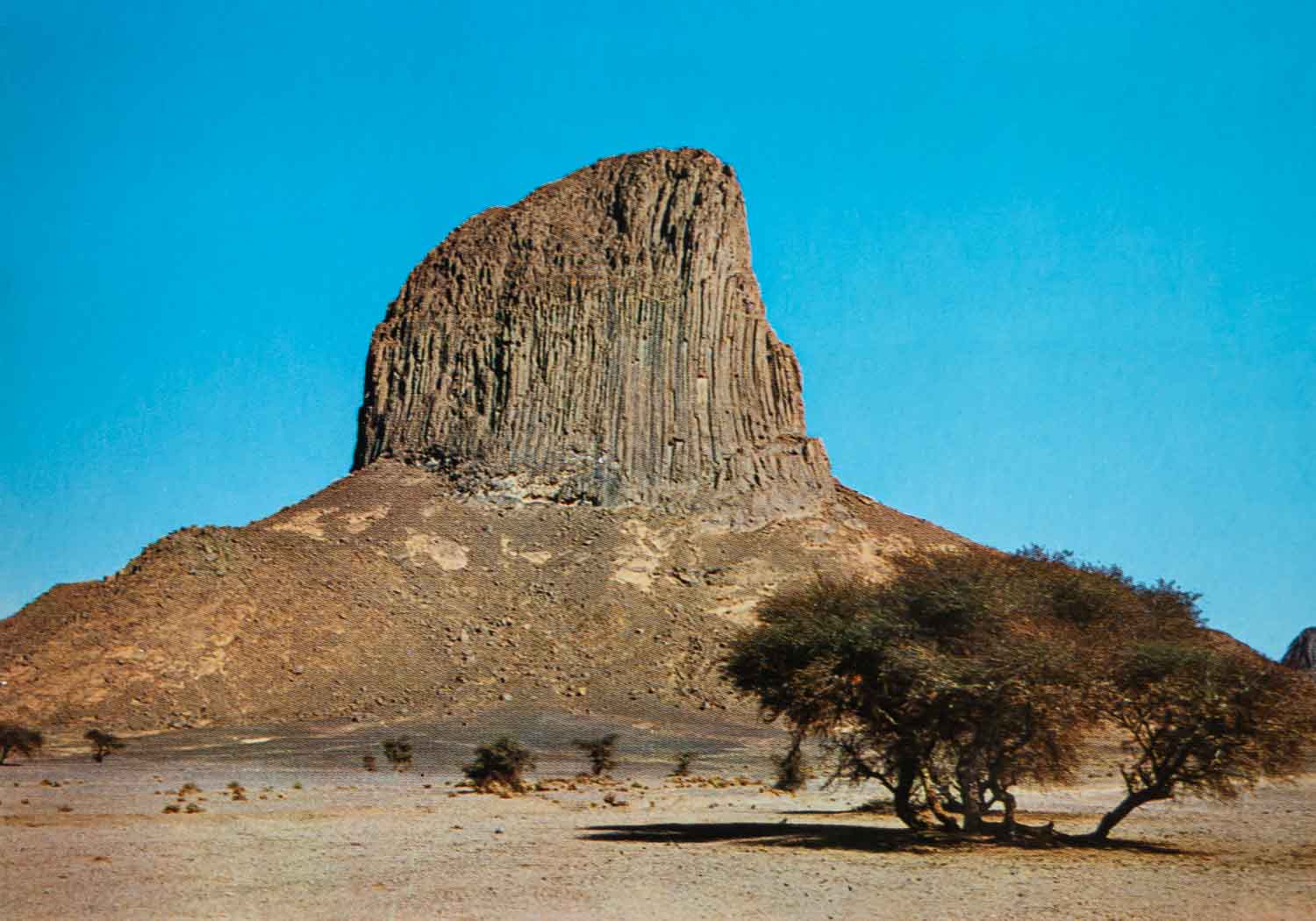

In the distance rise the basalt peaks of the 10,000 ft Hoggar Massif, including Iharen Peak, one of the iconic buttes.

Here are rocky mountains instead of sand dunes,

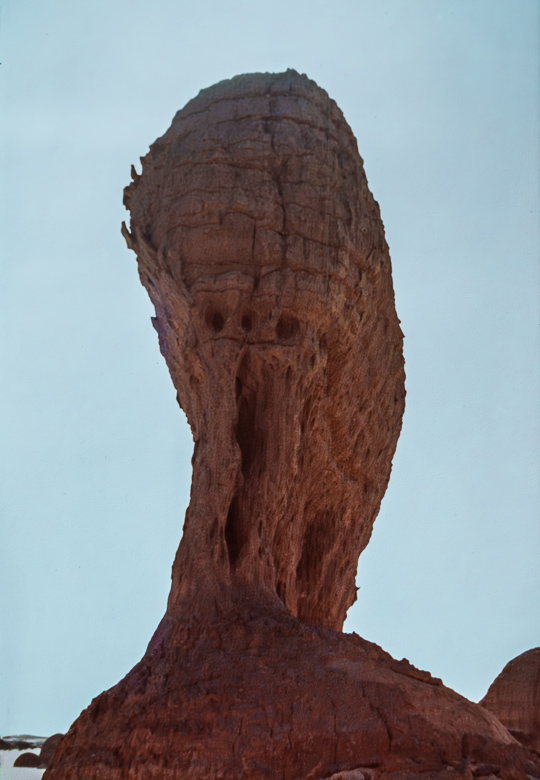

and all around us are gnarly twisted rock formations arising from the desert floor.

In some places we stop early enough in the day to set up camp and prepare dinner, and to climb. My burnt foot is covered in a bandage and a thick sock; I don’t let it slow me down.

When the wind blows it can be surprisingly cold, especially climbing up on top of the sandy-rocky walls.

And every day we make progress northwards, sometimes a slow slog, sometimes rolling along.

There is really no road, just a path that can become very rough and sandy very quickly. The diversity of the Sahara is surprising. I suppose most of us most of the time think only of the rolling oceans of sand,

but the truth is you can be surrounded by sand one day, a vast flat expanse that stretches to the horizon in all directions, and be in a canyon of grey rock the next, the “road” gravelly and rocky and unforgiving. North of Tamanrasset it is a mess, more potholes than road. It was paved in 1978 but just two years later it is disintegrating and frequently covered in sand. In places the pavement has completely disappeared. In some areas small cairns of rocks mark the route. Occasionally we see the desiccated remains of abandoned, stripped-down, wrecked vehicles, each a mute story of a star-crossed attempt to cross this vast arid wasteland.

North of Tamanrasset is a small white building, a rare manmade structure in the desert. It is the tomb of Moulay Hassan (not to be confused with the current prince of Morocco) a marabout, or Muslim holy man, who died while on a pilgrimage to Mecca. It has become traditional to circle it in your vehicle three times for luck. So of course we do. Who would want to risk not doing it?

North of Moulay Hassan’s tomb we come to the oasis of El Golea, now known as El Menia. Ahhhhhh, the relief of green. And shade. Palm trees are life! We fuel up, fill the water tank, collect what wood we can, buy supplies.

And so northward to the next oasis, Ghardaia, for another brief respite from the desert.

This land swallows you whole,

inhales you in its vastness.

One is reduced to the size of a zero,

a cipher, nothing at all.

There is nowhere to go in this empty place

dominated by sand and rocks

and above all sky;

a sky so infinite it sucks the life from you

and speaks of eternity.

The hot desert winds drain you,

and then, in a kind of wicked chuckling joke

they become surprisingly cold.

Undulating sand seas,

billowing oceans of sand

call to you to frolic, to climb, to roll,

to immerse yourself in their yielding softness

but the burning days

heat them as in a furnace

and so they remain something of an enigma,

too much shapeshifter to be trusted.

This is a barren land of emptiness,

of extreme heat and cold nights,

of fiery oranges, blushing pinks, and deep, rich ochres

stretching to infinity.

The silence is total and absolute;

the silence of the desert when there is no wind

is unmitigated, miraculous;

simply listening fills your ears

with a mute thunderous roar.

Beneath a blue, blue desert sky

is the fear of getting lost,

if not on the land then in the brilliant sunsets,

or above in the canopy of stars

that are so close it feels as if

they could you pull you forever

from this earthly existence.

There is no place like the Sahara.

It invades you, and always wins.

From Ghardaia, in a north-south zigzag, we aim west, eventually crossing into Morocco at Zellidja Boubker. From there we make a bee-line west to the city of Fes.

Next post: Morocco: a haven for hippies and I am in heaven. Fes, Marrakech, a good date, and a bad date.

Disclosure:

1. I’ve changed the names of everyone involved for privacy.

2. Obviously any photo with me in it was taken by another member of the group, but I’ve no idea who. We all swapped photos when we got to London.

Previous posts:

1. The Drums Of Africa. Botswana and Zambia.

2. Tanzania Mania

3. Wildlife And Tribal Life In Kenya

4. The Opposite Of Glamping

5. Turn left At Sudan

6. Mud Luscious and Puddle Wonderful. Central African Republic

7. Becoming Unstuck. Central African Republic

8. Waiting For The Rabbit To Die. Bangui, Central African Republic

9. Between The Jungle And The Desert: Cameroon and Nigeria

10. Sahara Prelude – traversing Niger

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

A super post. I have been to Erg Chebbi… Next post? Loved the poem. Also liked the pictures of the Buttes, especially the one that looks like an Edvard Munch. Thanks again. This is an epic in the true sense of the word.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Keith. I’m glad you enjoyed the post. It was both challenging and rewarding to put it together, to place myself back there feeling the nonchalance of youth. I wrote the poem as part of writing this post, not at the time. The open space there – so boundlessly wide open in places – makes you feel both small and infinite at the same time. That Edvard Munch butte is something eh.

In looking back I realize the entire journey was truly epic, though I had no sense of that at the time; it was just something I was doing.

Alison

LikeLike

Your photos are stunning!!! Incredible travel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Suzy. It really was incredible. In some ways I’m only now beginning to realize that.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

“To be clear, there is no road” really does define the Sahara. Loving your descriptions. They take me back to my three expeditions there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Peggy. Even with the “paved” section from Algiers to Tam (and a bit beyond I think) there’s still no road; the sand just blows in and covers great sections of it lol. And the rest is full of potholes apparently. You can find photos of this lovely long paved highway but the reality is a little different.

There being no road reminded me of traversing the Bolivian high desert – great sections of it the same thing.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Epic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was, though at the time, with the nonchalance of youth, I didn’t think of it that way. I was just doing what I was doing, having a big adventure.

Alison

LikeLike

Oh for a good dose of nonchalance, Alison 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again, another epic post, Alison. I’m really glad that you decided to write about your experience. I am going to have to hassle Tom to show me his slides from the journey. Your photos do a good job of capturing some of what you had to deal with, and your words the rest. And a poem! Thanks. –Curt

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Curt. I always knew I’d eventually document this journey, and it’s been so rewarding to finally do it. It’s been such a wonderful creative project to finally describe in words what we went through. Only a couple more posts to go. Then I might do the ’78 4-month trip I did in South America. That too was epic. I’d imagine Tom’s slides would be amazing. Thanks re the photos – wish I’d taken more.

Alison

LikeLike

Kind of like my six month solo bike trip around North America, Alison. There is just something about epic journeys, although mine was never far from a restaurant. Grin. By all means, do your South America journey.

As for photos, it was not the age of the digital camera! My experience in Liberia was similar to yours.

LikeLike

Stunning pictures! I’m trying to imagine having feet tough enough to walk on the sand. I ran barefoot as a kid in Wisconsin summers, but I didn’t ever get tough enough to walk on the hot roads or sidewalks.

The way you describe getting lost in the desert is the way I feel when I stand at the edge of the ocean. I suppose most folks find it scary to feel that small. I find it comforting to know that my petty problems really only matter to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Felicity. I’ve pretty tough feet from a childhood at the beach in the Aussie summers, but not tough enough to walk on hot coals! 😳 These days I still prefer to go barefoot whenever I can. I like how you describe the feeling when you’re at the ocean. It certainly puts things into perspective.

Alison

LikeLike

When I went to Wadi Rum in Jordan, I remember thinking how vast the desert was. I know the Sahara is much more expansive than that. But through this post I tried to imagine its true scale and how it makes everyone traversing it feel insignificant. Yet, it’s incredible to think that people do live there. The Tuaregs are definitely a force to reckon with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I felt the same in Wadi Rum, and really wish we’d had more time there. Even if the Sahara is more extensive you can only take in so much at a time. Still, traversing it made us focus on only the day at hand. Thinking of how far we had to go at any point would have been overwhelming I think. I agree re the Tuaregs – what a truly amazing group of people!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your writing took me along with you on the journey. Wonderful descriptions of the vastness and variety of the land. This isn’t putting the Sahara high on my list though. 😊 Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Maggie. I’m glad I could give you a little taste of what it was like to be there. I think anyone heading into the Sahara these days would be mad. I’m so glad I got to go when I did.

Alison

LikeLike

The romance of crossing a desert is intoxicating, but my chances of ever doing what you did in the Sahara are clearly gone (the Chris Scott paragraph gave me such FOMO!). I did get a taste of the endless, unmarked, scary-if-you-think-about-it expanse of the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. That’ll have to do! Another awesome post – thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lexie. Chris Scott really makes it clear Sahara tourism is currently a thing of the past doesn’t he. I’m so glad I got to do it when I did. Lucky! Still the Gobi sounds pretty incredible. I highly doubt I’ll ever get there, though I’d love to. Mongolia! That would be amazing.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even the deserts of SW United States can seem like they go on forever – I can’t imagine the vast dry suck of the Sahara. I get intimidated just thinking about it, regardless of the era.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vast dry suck is a great way to describe it. Though it is truly magnificent in places, it’s definitely intimidating; definitely not a journey to be undertaken lightly.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this thrilling read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure; I’m glad you enjoyed it. It was a truly remarkable journey. I can scarcely believe I actually did it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

In my humble opinion, deserts are underrated. They suffer a bad reputation as places of crippling heat, hostile to life, and devoid of redeeming characteristics. I find that Africa’s deserts are full of stunning geological formations, unique animals, hardy plants, and sweeping dunes. While I loved the Sahara Dunes, I have my eyes set on visiting the Kalahari Desert in South Africa. Thanks for sharing, and have a good day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Deserts do seem to be underrated, but get into one and you quickly discover how magnificent they are. I’ve not been to the Kalahari, but would love to one day. You too have a lovely day.

Alison xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

🥰🥰🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

We are there with you, reading your excellent descriptions of the vast Sahara. I would be a bit terrified, except for confidence in your experienced guide. It must have been like morning dawning in relief when you saw green ahead at an oasis!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Ruth. I don’t remember ever being frightened on this whole journey – the nonchalance of youth I think. It simply never occurred to me that Craig would not be able to get us through. Fortunately nothing so bad happened that he could not. I think our trip was charmed as there are certainly some horror stories of the overland groups of the time.

And yes, we were so relieved to get to those oases.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

1980s were a Golden Age for desert tourism ~ and you were able to experience and capture the mood and scene. How beautiful 😊. To have ridden, camped, explored, and just experienced the Sarara at a time of freedom in the 80s, the camel caravans and wells to drink from – a dream, Alison. It must have been fun reflecting back on these travels, the stories, and of course the great photos taken (gotta say, I love the ‘no privacy’ photo 😂, it’s what traveling with friends are all about!).

Thinking back on such experiences, especially the opportunity the Tuareg man offered about accompanying him back to his village and not taken, is something that fuels dreams and wonder. It’s probably a smart choice, but like you, I can’t help wondering… what if?!? One impressive thing are the scenes of how vast, isolated, and beautiful the desert can be… invigorating to the soul. The poem gives this feeling beautifully, especially the last line “There is no place like the Sahara. It invades you, and always wins.” Once again, it was a beautifully written post, and it was such a joy to read and feel alive again 😎.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Dalo, I’m glad you enjoyed it. It was a truly amazing time, and looking back I can hardly believe I did it. And even after all these years I can still invoke the feeling of the Sahara and write a poem about it. It’s an extraordinary place.

Putting together all these posts of the Africa expedition was a truly wonderful creative exercise; fun, yes!

Alison

LikeLike