This is the tenth instalment of a four-month trans-Africa trip from Johannesburg to London that I did with Exodus Expeditions in 1980, travelling by ex-army truck and camping. We were not sightseeing, though we did see some incredible sights. Our goal was to see and experience Africa from south to north by whatever route was open. Four months. Twelve people. One truck. Fifteen countries. 18,000 kilometres. Links to the earlier posts are listed at the end of this one.

*********************************

We exit Nigeria just north of the town of Illela, and enter a no-mans-land. The entry into Niger is ahead. There is nothing around us. No buildings, no customs office. Craig stops the truck. He tells us to lay the tarps out on the ground and take everything from the truck. Everything. All is to be spread out on the tarps for easy inspection. He tells us that the border is manned by convicts. There is nothing around for what seems like infinity so where are they going to go? We are in what’s known as the Sahel, a semi-desert region up to a thousand kilometres wide stretching east-west across Africa just south of the Sahara. It is very dry, and largely uninhabited.

We stay by the truck with all its contents revealed; we see in detail how much we have. Craig disappears into the distance. We wait. Some time later, a half-hour maybe, he returns and tells us we’re cleared to go. I guess the guards were feeling kinda lazy, though I suspect they’re more interested in catching contraband in the huge transport trucks than checking on a ragged band of white western travellers on the overland route. From the border we go west all the way to Niamey, the capital of Niger, and back, to get visas for Algeria. It’s 380 kilometres each way on a paved road through increasingly sandy terrain. We stop in Kore Mairoua for supplies, and even though we’re very little north of the border with Nigeria it feels as if we’ve entered a whole new world.

Niger can be divided into three distinct geographical regions. In the south there is some cultivation. It is in the Sahel, the intermediate region, where the Fulani and Tuareg nomads spend the summer. To the north is the desert zone. The Sahara Desert covers all of the north, more than half the country, making Niger one of the hottest countries in the world. Only one-fifth of the population live in towns, and of the many villages half have a population of 500 or less; there are almost no villages in the desert zone.

In this sparse sere country, with hardy desert scrub clinging resolutely to life, we pass by a few remote villages,

herdsmen with their livestock,

and people who are both shy and curious. A small family group in this parched land, their lives as alien to me as mine is to them, watch us as we go by.

Both the Fulani and Tuareg live in tribal groups, in temporary or portable shelters. Their livelihood comes from their animals. The Fulani raise sheep, goats, and longhorn cattle, and live largely on milk in various forms; the Tuareg also raise sheep and goats, as well as camels, and eat mainly meat and dates. And in the vast desert wilderness both groups know where all the wells are located.

Back close to where we first entered Niger we finally head north again, towards the town of Agadez, and the Sahara, and into the land of the Fulani and Tuareg. We see groups of Fulani herdsmen with their long-horn cattle. This group is at a well, raising water in skin bags for their livestock,

and it is here that Steve, who is just about the most useful and competent person of our whole group, uses his first aid kit to help an injured herdsman.

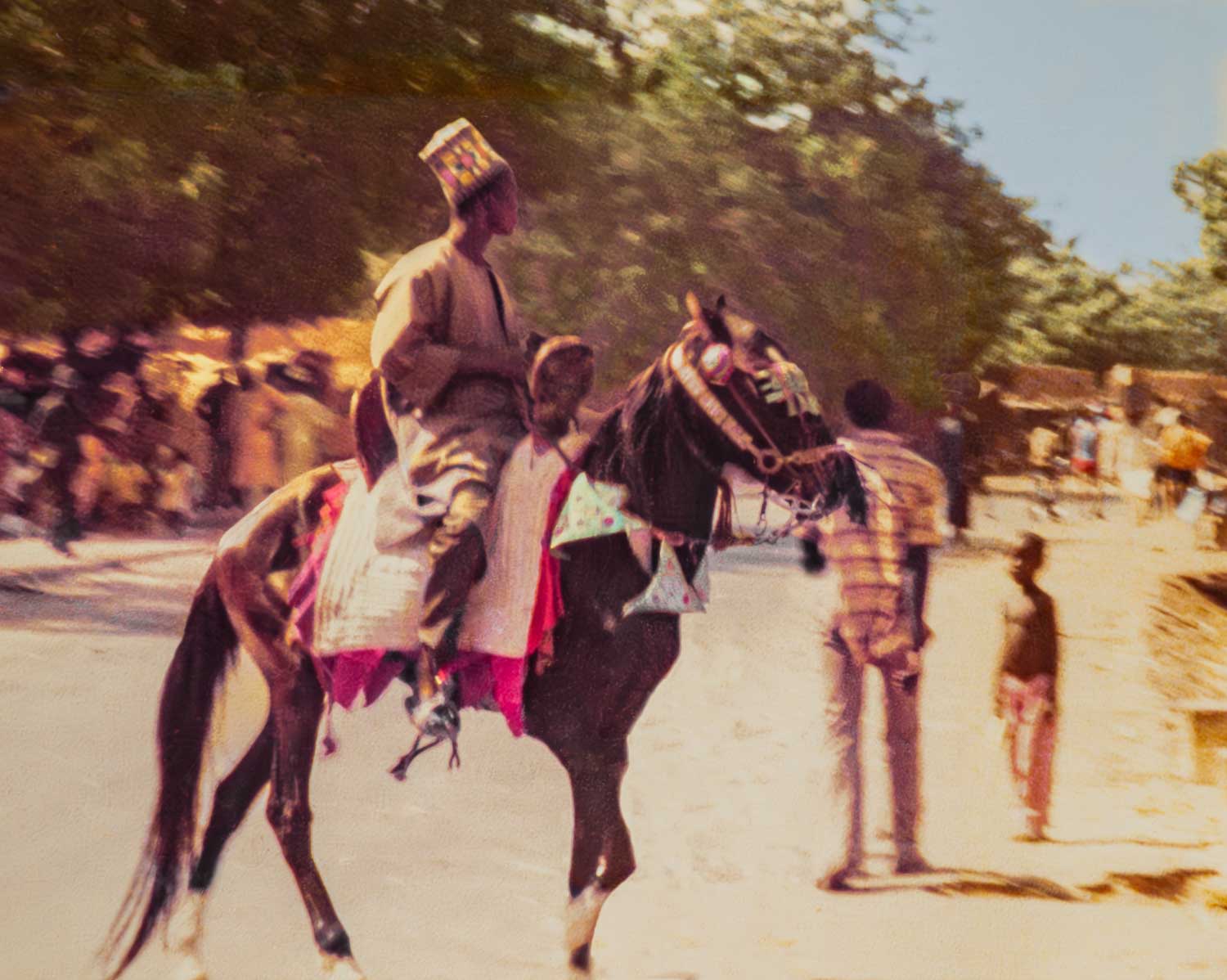

As we journey along, the occasional lone horseman appears in the emptiness,

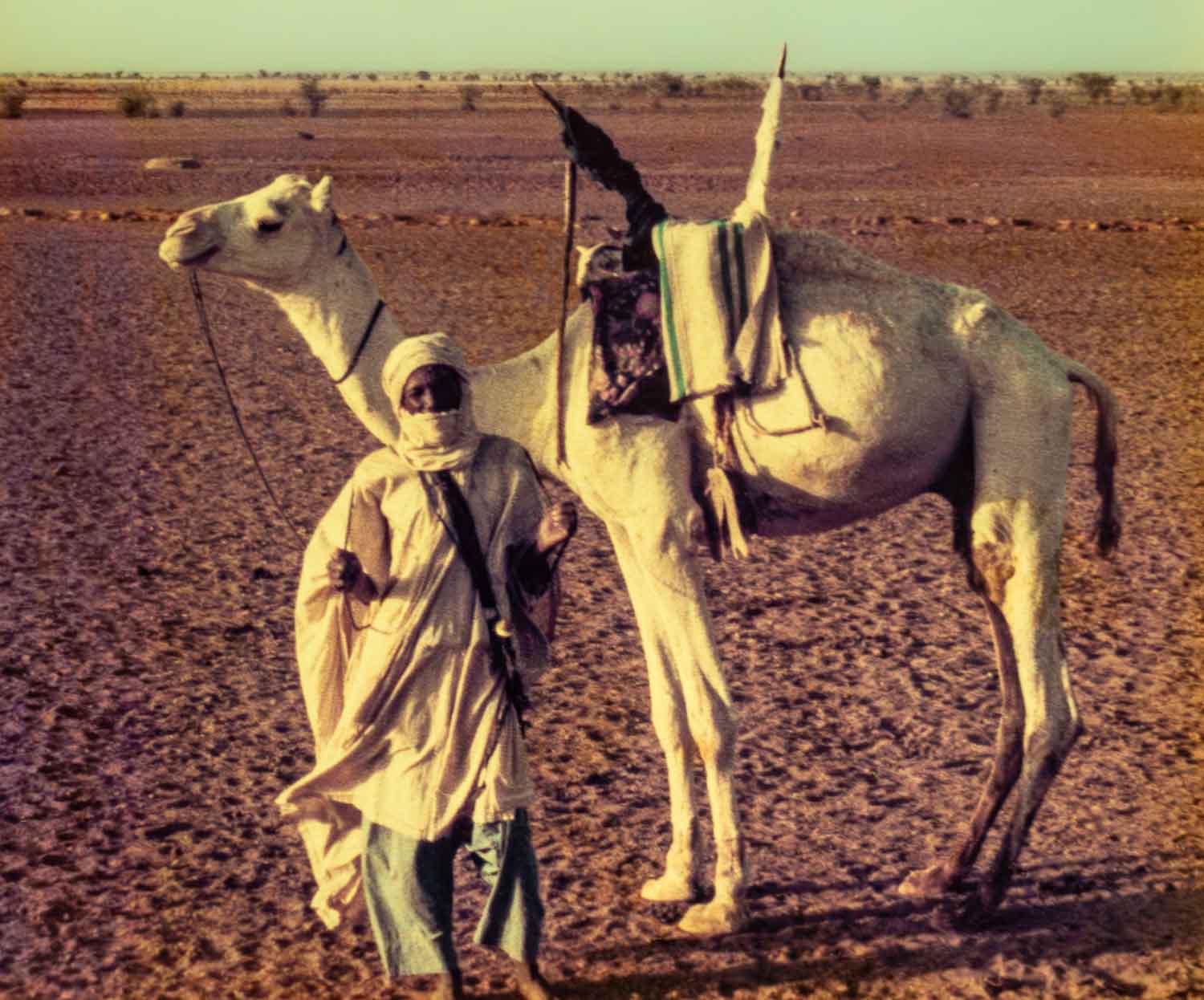

or a Tuareg man with his camel.

There is nothing for miles around, no sign of any villages or human presence; it feels as if we are alone in this vast barren landscape so such sightings are always a surprise. I notice that their connection to their animals always seems so organic; a unity that is both seamless and elegant.

The days are long and hot. There’s some relief at night if there’s a breeze, but if not the nights too are sweltering. Nevertheless, on November 5th we have a bonfire.

Most of us are British, or of British heritage, so November 5th is a date that’s seared into our memories by a childhood rhyme.

Remember remember the 5th of November

Gunpowder, treason, and plot.

I see no reason why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

It is the date in 1605 that a man named Guy Fawkes tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament. Everyone builds a huge fire to burn an effigy of him. We’re still in the Sahel, have not yet entered the Sahara proper, and there’s wood available, so we make the most of it. Perhaps we all just need a little entertainment, as if we’re not already hot enough.

Most nights I don’t bother with a tent. Whenever possible I string my mosquito net from a bush and sleep out under the stars, but as we head north the land becomes more and more sandy and arid until there is no plant life to be seen, nor mosquitoes. Agadez is the halfway point to the border with Algeria. The road is still good, though with areas of billowing sand. About a hundred kilometres or so before we reach the town we seem at last to have entered true desert. And there’s this about the Tenere, which is just east of Agadez:

The Sahara is the biggest desert on earth. It takes its name from the Arab word for emptiness. In the dead heart of that emptiness there’s a place called the Tenere. The Tenere takes its name from the Tuareg word for nothing. A nothing the size of France in the middle of an emptiness the size of the United States. It’s no wonder the locals call this place The Land Of Fear. David Adams

The oasis of Agadez is a town of orange mud brick buildings so blending with the landscape that it’s as if the land itself gave birth to a sea of geometric forms that rise organically from the flat plain.

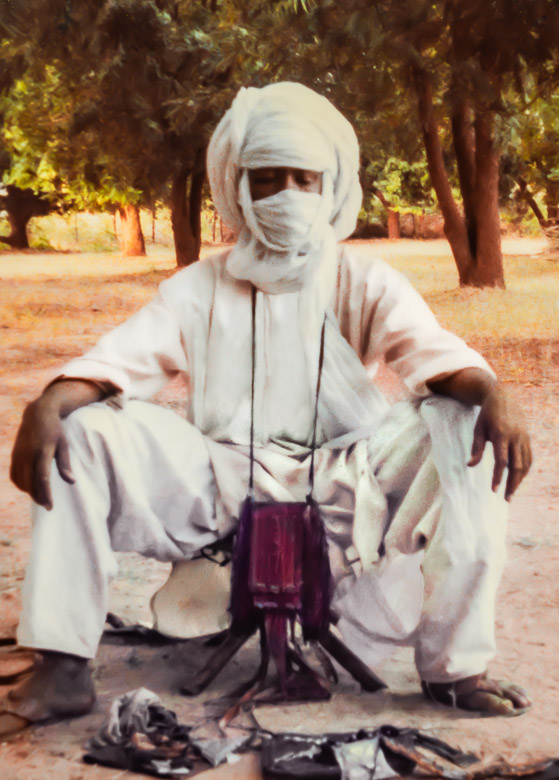

Here we meet some of the Tuareg people.

I have a halting conversation with a Tuareg man who wants to sell me one of their traditional purses. The conversation is in French, the official language of Niger. Craig sits nearby and smiles at my efforts. My French is far from fluent but gets the job done, and I purchase the very purse hanging around his neck.

Approximately 200 kilometres northwest of Agadez is a tiny village of about fifty families called Teguidda-n-Tessoumt.

The population is seasonal. They are employed in an unusual, and ancient, salt industry where they extract salt from clay. The area is dotted with dozens of ponds filled with brine water from springs. Entire families work here.

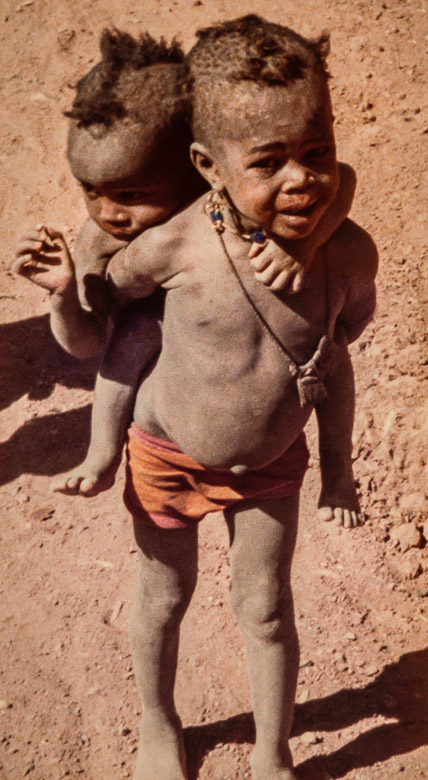

Children who are too young to work take care of those even younger.

The hills are from the buildup of clay from which the salt has been extracted.

The salt is used as a dietary supplement for animals, and in the winter both the Fulani and the Tuareg gather in the area for their animals to benefit from it.

The further north we go the more the road is swallowed by the desert, until it becomes a wide expanse of tire tracks surrounded by an infinite emptiness. Every few kilometres there is a marker barrel – a fuel drum filled with sand – indicating that you are still on the “road”. Deviating from the track could be deadly. We stop frequently. Up on top of the truck Cameron searches for the next marker barrel.

If it’s not the wind, the truck itself stirs up a light dust, which drifts down onto everything – our bodies, our clothes, the truck inside and out, our food. Everything. Coupled with the sun, we begin to understand why the people of the desert are swaddled from head to foot in cotton cloth.

We pass Arlit, the last town in Niger, and dive deeper into the Sahara. There are over 2000 kilometres still to go. It already feels as if we’ve been in the desert forever, and we’ve only just begun.

Next post: Algeria and the Sahara.

Disclosure:

1. I’ve changed the names of everyone involved for privacy.

2. Obviously any photo with me in it was taken by another member of the group, but I’ve no idea who. We all swapped photos when we got to London.

Previous posts:

1. The Drums Of Africa. Botswana and Zambia.

2. Tanzania Mania

3. Wildlife And Tribal Life In Kenya

4. The Opposite Of Glamping

5. Turn left At Sudan

6. Mud Luscious and Puddle Wonderful. Central African Republic

7. Becoming Unstuck. Central African Republic

8. Waiting For The Rabbit To Die. Bangui, Central African Republic

9. Between The Jungle And The Desert: Cameroon and Nigeria

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

Incredible adventure Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was! So glad I did it, and so happy to be reliving it now.

Alison

LikeLike

Love the commentary and pics. I so wish we would have made it into Niger.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Peggy, glad you’re enjoying. Really recommend you click on the David Adams link above – truly amazing documentary about the Tuareg in Niger. I think you’d really enjoy it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow!!! What an amazing story…

Being my birth year, 1980 is special to me 🙂

4 months and 18000 km in Africa, an incredible adventure indeed!

Thank you so much for the incredible effort you put in documenting this epic journey through these photos and sharing with us.

Let me start reading from the first post 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you is much Sreejith. It really was the most amazing adventure, and what we did still astonishes me. It is a very great pleasure to be reliving it, and sharing it now.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could see it 🙂

It teaches a lot on how we should document our travel as well.

Thanks again for sharing and wish you be able to travel a lot more and share your stories with us.

Have a beautiful Sunday 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a desolate place and what an amazing way to see it. Thanks for describing it so well. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Maggie. I’m glad I’ve managed to evoke a bit of what it was like. Not all desolate though (though some for sure was) – watch the David Adams documentary linked above about the Tuareg. Amazing amazing amazing!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you still have the purse? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was my first question too!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sadly I do not. Three times in my life I’ve divested myself of (almost) all my stuff, and the most ruthless time was when I moved to Canada in ’84 – that’s when I let it go, along with a beautiful Tuareg saddle cloth.

Alison

LikeLike

What an amazing experience. You describe the dessert so well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Darlene. Looking back I can hardly believe what we did.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I very much enjoyed reading about your wild African adventures, Alison and seeing all the photos. Going overland across Africa for sure creates memories that last a lifetime. Reading your post reminded me how vital it is to organise your adventure travel photos for saving your memories and making them easily accessible for future reminiscing. Plus, it can save you from the frustration of scrolling endlessly through hundreds (or even thousands) of photos to find that one perfect shot you remember taking. Thanks for sharing, and have a wonderful day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Aiva. I’ve been wanting to delve into these memories for a long time, and now that I’m finally doing it I get to live it over again a little bit. It’s not the same as being there, but nearly. I did have my photos arranged in a scrap book, with a few notes here and there, so I mostly knew what they were of, but I really wish I’d been more diligent about that, and especially that I’d made more notes at the time.

You’re welcome – sharing is my pleasure 🤗

Alison

LikeLike

🥰🥰🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a strange border crossing! Still, I’m glad that it was uneventful. The alternatives are much more … exciting. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol, the alternatives to uneventful could have been much more exciting! 😂(And not necessarily in a good way). I don’t think it’s like this anymore, but could be wrong. I doubt the government would advertise that its border guards are convicts.

Alison

LikeLike

I’m continuing to read about your journey through Africa, still hesitating between the desire to experience the same thing and the apprehension of what it represents.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In many ways it’s much better these days. For one thing most camping nights are spent in proper campgrounds with facilities, and trucks are far better equipped for wild camping, and also I think only about 75% of nights are camping. Most importantly AFAIK no overland company goes through the most unstable countries (CAR, Sudan, Niger, etc) so it’s both safer and more comfortable. I can’t recommend a company of course, though have come across Dragoman, which looks quite good. Also leggypeggy (see comment) has done some fairly recent Africa overland tours. Follow the link to her blog to read more about them and find out who she went with.

Alison

LikeLike

Thank you, that feeds my reflexion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Somehow I get the impression these folks would be astonished by what constitutes first world problems.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed. It may be a little different now with the internet and cell phones, but still, in many places I think life continues much as it always has done, and Niger is still one of the world’s poorest countries. OTOH I was absolutely delighted that at the recent Vancouver Folk Festival there was a band from Agadez! And they were truly cool guitarists – rockin’ world music dressed from head to foot in traditional Tuareg robes. Watch the David Adams doc I’ve linked above – amazing!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Sahel is yet another relatively remote but fascinating corner of the earth I’ve been intrigued by for quite some time. I have placed a great interest in the region’s mud brick buildings and the mosques built in an architectural style found in no other places on the planet. I am continually impressed by the stretch of which of this particular adventure was carried on, Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Honestly, I’d never heard of the Sahel until I started researching this post – or if I heard of it at the time I have no memory of it. And I didn’t see the mud minaret in Agadez, or was not impressed enough to photograph it. It amazes me what I *didn’t* photograph on this journey compared to how I see things now. Also we really had no way to get information – no internet, and very few guide books, and AFAIR none of us had a guide book with us. Reliving this journey makes me want to back and explore more, see some of what I missed.

But you’re right – we covered a lot of ground through a very wide variety of landscapes and cultures, so definitely got an amazing broad view of the continent. Like I said to some of the others I really encourage you to watch the David Adams documentary linked above.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

You remind me of my trip to Europe back in 2007. I didn’t take photos of things I would definitely capture with my camera today.

I will for sure watch the documentary. It looks and sounds right up my alley!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just watched the documentary. It’s amazing! I love how the local Tuareg guide checked the camel droppings to see how far the caravans were from them. The dune skiing looks fun, but hot!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t it a fabulous documentary! I loved it. And it’s quite recent, so things haven’t changed much. Sadly we did not see a camel caravan 😢

LikeLiked by 1 person

Everything is so big – the distances, the conditions, the experience overall. Staggering in so many ways. I am in awe of your bravery and sense of adventure. Yes, I tend to have those, too, but I’m not sure I could have managed a trip like this .. glad I can live it though you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lexie. I doubt I could manage a trip like this now – though I sometimes dream of being able to do something like it again one day. I suppose I’m nothing if not an adventurer. At the time I can promise you it did not feel like bravery at all, just something I wanted to do as soon as I became aware of the possibility. In researching for this series of posts I’ve come across one or two similar tips in Africa that got into some serious trouble with the truck, or people getting sick (jiggers, malaria) but we had no such problems. Just lucky I guess. And an excellent leader. Our journey was at times arduous, but never felt unsafe. I’m glad you’re enjoying travelling vicariously with me. I so much wish I’d made notes, and/or that I remembered more.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

That must have been an incredible trip!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was. Of all my travels, this was probably the most amazing. I wish I remembered more.

Alison

LikeLike

Sounds close to the ultimate in isolation, Alison. My friend Tom, who did what you did about the same time except going north to south (Bone went with him, BTW) got stuck in the Sahara when his truck broke done. Fortunately it was near a French mining camp that they were able to hang out at as parts were hipped from Europe. The cook at the camp was excellent, so Tom became an apprentice to fill in his spare time. Tells me that he learned a great deal. –Curt

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was isolated for sure. We were in such a bubble in the truck, but still aware that there was nothing much around us for miles in every direction, especially once we got into the Sahara. Tom’s experience sounds amazing. I presume the cook was French, or had learned from the French? What a way to learn to cook!

Alison

LikeLike

As I recall, the cook was French. Laughing, I’m reminded of when I rode my bicycle up into northern Canada. Isolation! And I was by myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Sahara journey sounds like an incredible adventure, blending rich cultural encounters with the beauty and challenge of the desert. Your descriptions of the Tuareg and Fulani people bring this journey to life, offering a glimpse into a world so different from our own. For those of us who love immersive travel experiences, exploring unique destinations like these is always inspiring. Speaking of which, if you’re ever planning a trip to Southeast Asia, Cambodia offers similarly fascinating cultural experiences. You can discover the wonders of Angkor Wat and more through guided tours at. https://mysiemreaptours.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind comments; I’m glad you found my post inspiring.

We were in SE Asia many years ago, and loved Cambodia. Of course we visited Angkor Wat while we were there. It’s an extraordinary place! We also went to Prek Toal bird sanctuary.

Alison

LikeLike

This is the most exotic adventure I’ve ever had the pleasure of following. The desert seems endless. Spreading out everything on the truck must have felt vulnerable, but I guess you didn’t have what they would have wanted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoying this series Ruth; I can assure you it’s the most exotic adventure I ever *went* on. It was so strange emptying the truck like that, but better to be prepared. No one even came to look at it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person