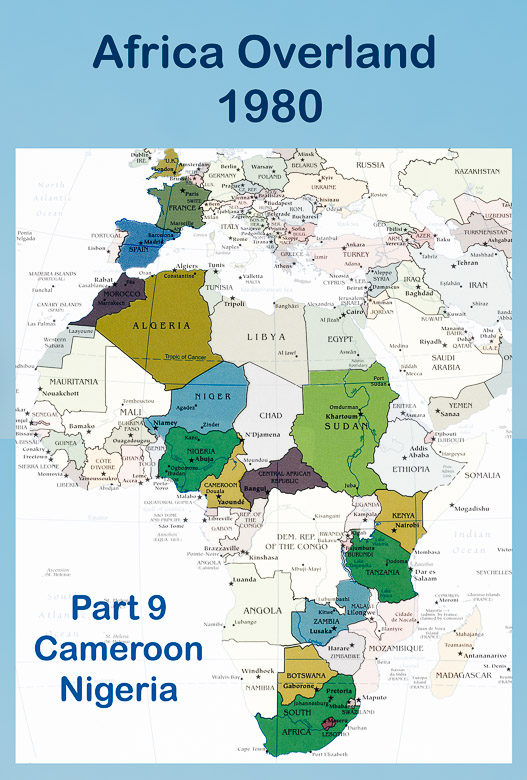

This is the ninth instalment of a four-month trans-Africa trip from Johannesburg to London that I did with Exodus Expeditions in 1980, travelling by ex-army truck and camping. We were not sightseeing, though we did see some incredible sights. Our goal was to see and experience Africa from south to north by whatever route was open. Four months. Twelve people. One truck. Fifteen countries. 18,000 kilometres. Links to the earlier posts are listed at the end of this one.

*********************************

A real kitchen! Indoor plumbing! A bathroom! What unexpected luxury . . . . .

A few of us are sitting on a bench next to a parking lot in downtown Kano, Nigeria waiting for the others who are shopping for truck supplies. A man approaches us and introduces himself, and we all chat for a few minutes. When we share that we are travelling overland through Africa, and camping, he offers his spacious yard as a place to set up camp. We are shocked; it seems an unbelievable offer! We explain there’s twelve of us, which doesn’t phase him a bit. That’s okay he says blithely. We learn later that his wife is away; perhaps on a trip back to England. I never do find out what his work is. Diplomatic? An aid organization? International corporation? Perhaps he just wants some company, and to mingle for a bit with his own tribe. We, of course, are delighted.

It’s almost 2000 kilometres from Bangui, Central African Republic, to Kano, Nigeria. From Bangui we follow RN1 north then head west on RN3 at Bossembélé. It’s then 450 kilometres to the Garoua-Mboulaï border crossing into Cameroon. After our slow painful slog through the central African jungle finally the roads, two-lanes and mostly paved, are unremarkable. Or perhaps I should say they are remarkable for their ease and our ability to make progress. The further north we go the better it gets. Until it doesn’t . . . . . . .

Situated at the convergence of western and central Africa, geographically Cameroon has a bit of everything: a small coastline with beaches on the west of the continent, across the south a continuation of the central African jungle that had proven to be such an arduous challenge for us, north of that a savanna, and the Mandara Mountains beyond that. The country is also ethnically diverse with more than 200 ethnic groups.

From Garoua-Mboulaï we head north, briefly skirting along the border with Central African Republic then continuing north to Ngaoundéré, capital of Cameroon’s Adamawa Region. And now at last we are beyond the jungle, out of the mud that clings to everything and makes progress almost impossible.

Here at last are open skies and scenery! After weeks in the jungle rediscovering the sky is a revelation.

We are travelling through the luxuriant greenery and thick forests of Cameroon’s savanna, and stop at peaceful Lac Tison, a small, deep crater lake surrounded by trees, about fifteen kilometres from Ngaoundéré.

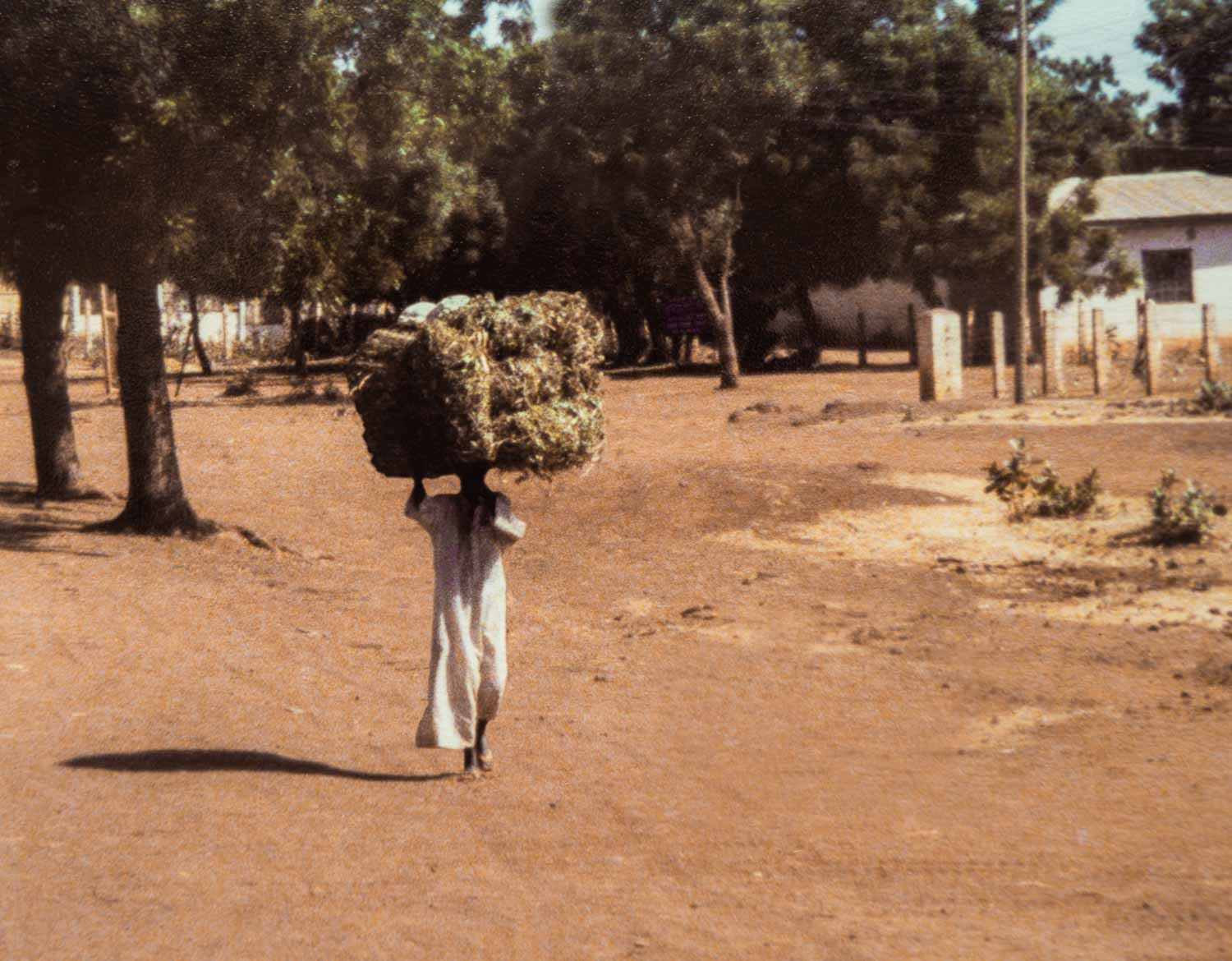

The Moslem influence becomes progressively stronger the further north we go. Many of the men dress in long, white or coloured cotton robes. We stop in Ngaoundéré, a lovely village with a beautiful mosque, and, as usual, friendly people. Everywhere we go we feel welcomed. At the market we buy fresh fruit and vegetables, but naturally we do not set up camp in or near a city, preferring to wild camp away from population centres and the possibility of thieves.

We continue travelling north, always north, passing villages along the way,

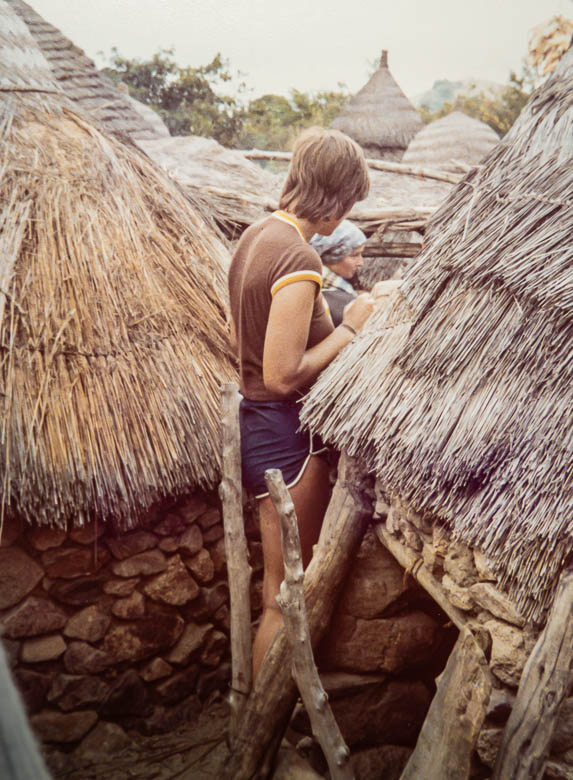

some of which would be the compounds of the Mafa or Matakam people. The Mafa people live simply in villages that are a collection of cylindrical huts with thatch-covered conical roofs.

Every house, or family compound, has a front court, a foyer, a room where the father of the house sleeps and keeps his belongings, a sacrifice room, the main granary, rooms for the women and children, and a kitchen. All these rooms are closely interconnected, in a roughly circular grouping forming a central private courtyard.

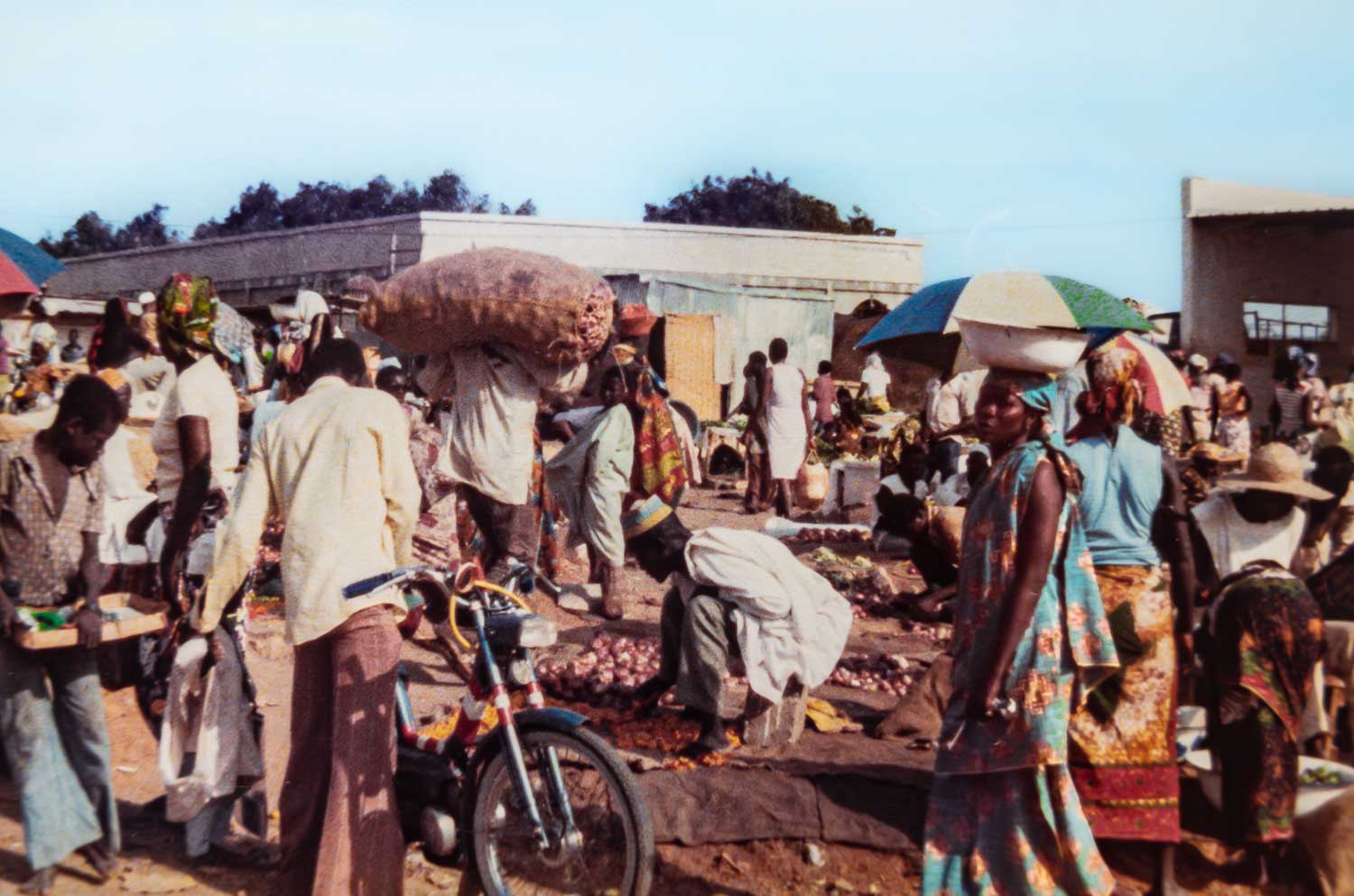

Eventually we come to Garoua, capital of the North Region, where we stop again for groceries at the local market. Like most “third world” markets, you can find almost anything in this chaotic bazaar; it’s noisy, alive, organised pandemonium.

From Garoua we continue north to Rhumsiki as the terrain becomes more and more arid, littered with rough granite rocks and boulders. Women in multi-coloured outfits work in the dusty fields tending their crops of peanuts, sorghum, millet, and maize.

Once again I sleep under the stars cocooned by the gently waving white gauze of my mosquito net. After the jungle everything eases. We are no longer so occupied with simply making forward progress, but can relax more into the journey, enjoying the passing scenery and villages.

It is now that we enter the unique other-worldly landscape of the Mandara Mountains.

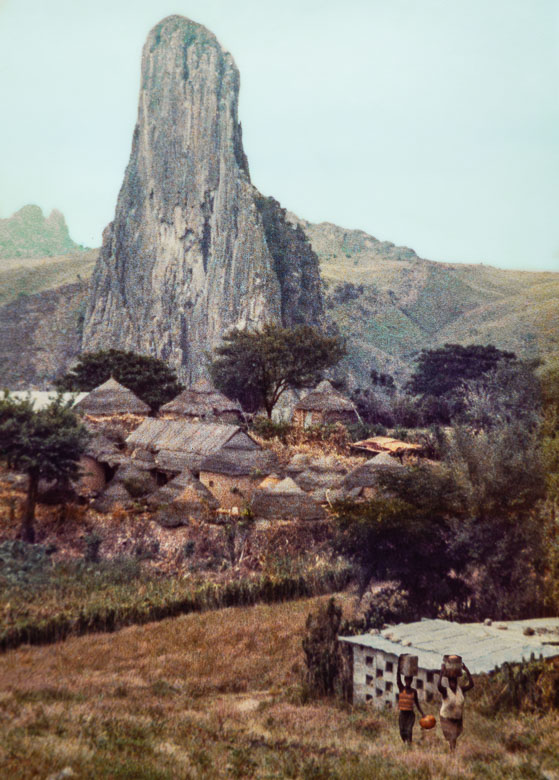

As mentioned, the north of Cameroon is predominantly Muslim. In the 18th century the Kapsiki, the ethnic group of this region, fled into the mountains because they did not wish to be converted to Islam, and they continued to live there practicing their animist faith. Sheltered in the Mandara Mountains, Rhumsiki is a village of less than 5000 people. It is situated on a high plateau punctuated with volcanic chimneys, some as high as 1000 metres. The most famous of these rocky needles is Mchirgué, also known as the Peak of Rhumsiki. With a height of 1224 metres it dominates this surreal landscape, with Rhumsiki clustered near its base.

At last we get to see inside one of the compounds. The huts are circular, built from local stone, with conical thatched roofs. Within the family compound are numerous huts, built close together, for the men, the women and children, kitchens, and a granary, all around a central courtyard. It is actually the chief’s house that we are allowed to enter, and after squeezing between the huts

we come to the central courtyard where a woman sits painstakingly grinding maize.

Skirting along the border even further north, we cross at last into Nigeria, travelling on paved roads north to Maiduguri. In Maiduguri we encounter a group of cattle herders.

Fulani cattle herders are virtually all Muslim. It is estimated that between 12 and 13 million Fulani are nomadic or semi-nomadic herders of cattle, goats, and sheep. They travel across large areas in West Africa to provide grazing for their livestock. For several decades there have been herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria over arable land resources between the mostly-Muslim Fulani herders and the mostly-Christian non-Fulani farmers.

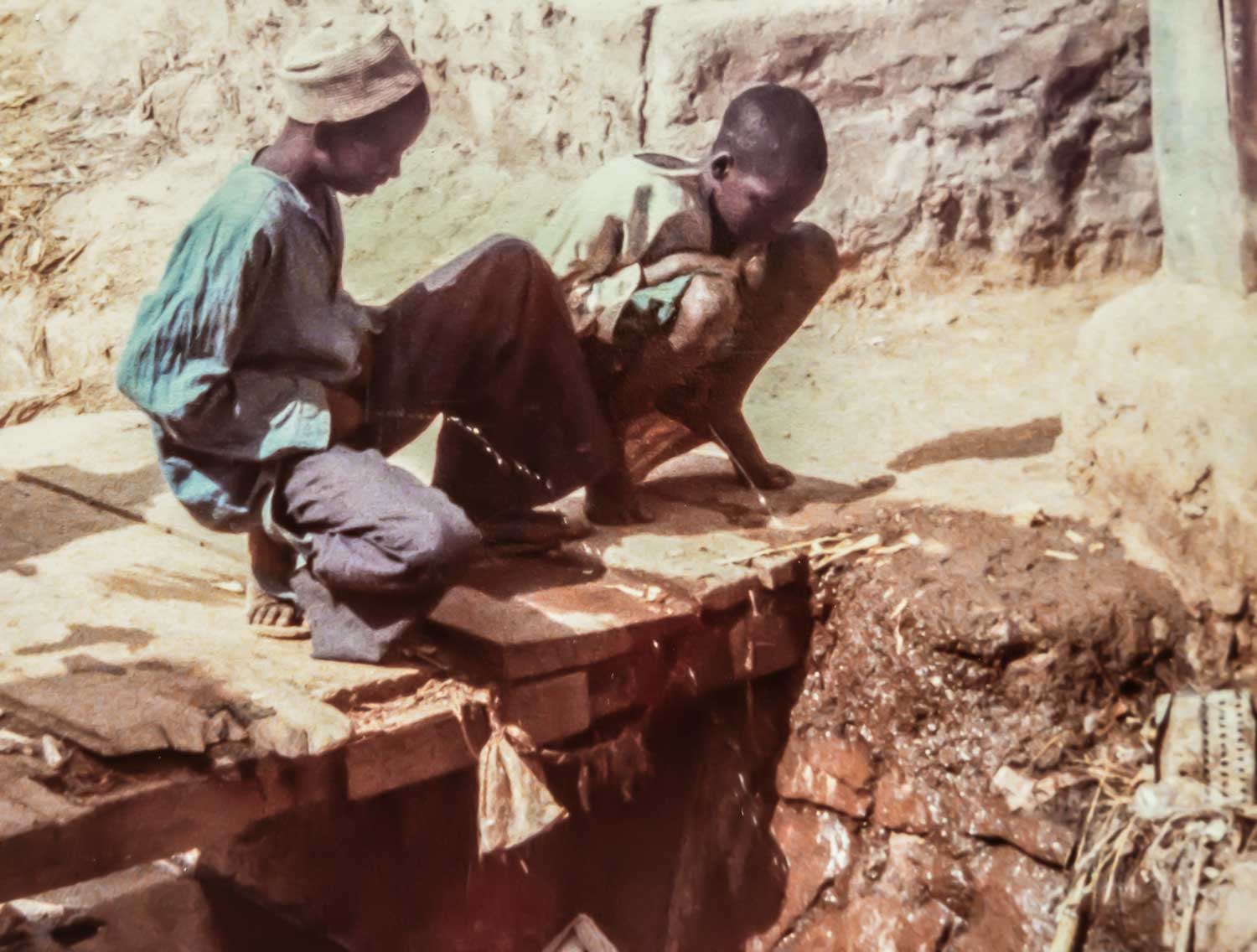

Meanwhile, when we stop in the towns, kids crowd around the truck. We are unique in their world, an oddity, strangers in a strange land. They are friendly and curious. Who are we? Why are we there? Where did we come from?

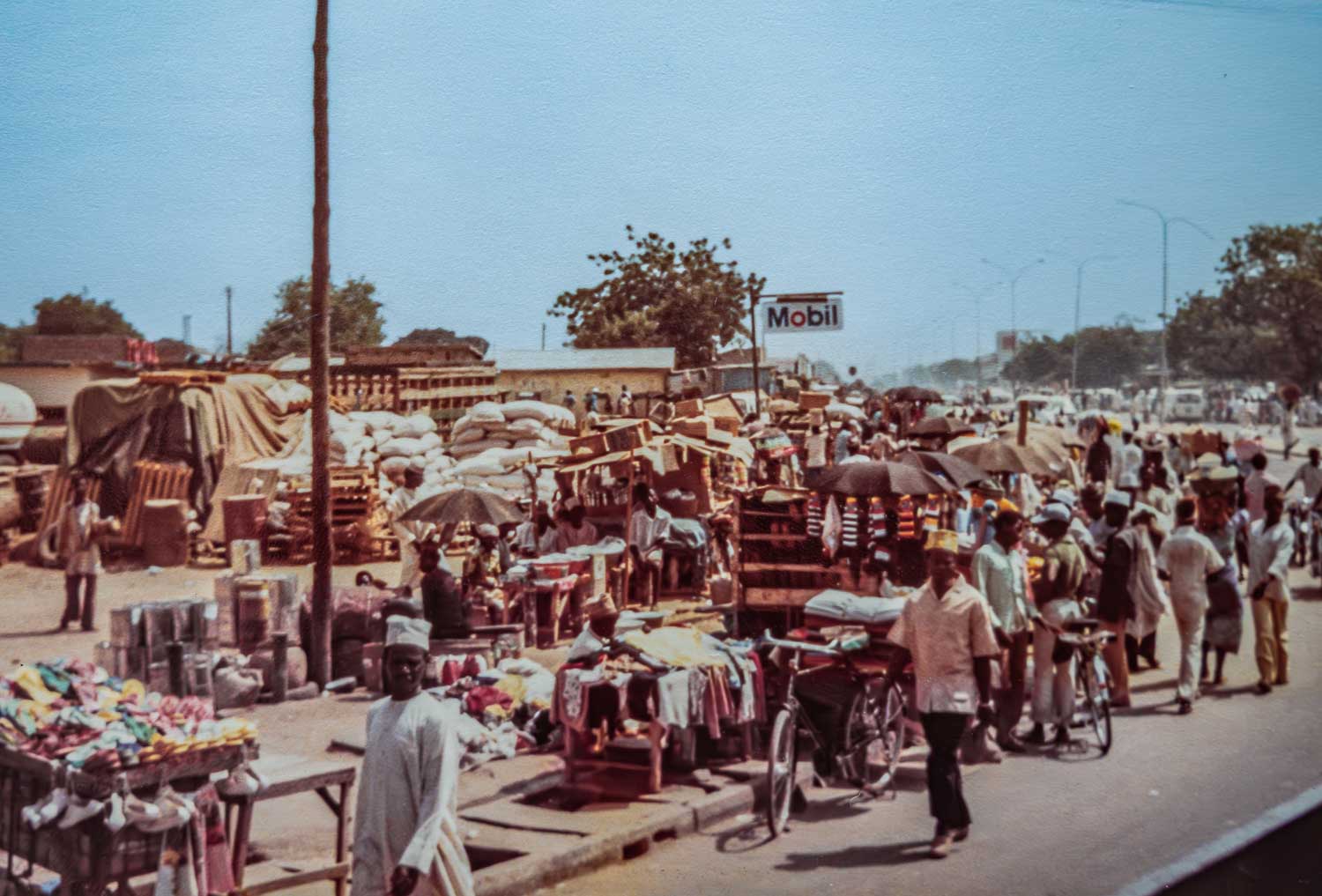

And so we continue on to Kano, Nigeria’s second biggest city. Kano is teeming. It’s a crowded city swarming with bicycles, cars, motorcycles, trucks, and exhaust; it’s all busyness and congestion.

We dive into the old town and market. Kurmi Market, established nearly 600 years ago, is on West Africa’s trade route, and was famous for the slave trade when it was founded in the 15th century. The market is visited not only by Nigerians, but also by travellers and traders from neighbouring countries. Textiles, spices, nails, silver, flour, and radios; along these narrow alleys with open sewers there are hundreds of small shops, and everything is for sale. There’s a sense that, except for the more modern goods available, not much has changed since the market’s inception; the centuries crowd in on one, evoking a living breathing impression of the past.

We regroup after the market, and wait with the truck while the others are getting supplies. It’s then that we meet Doug Lawson, he of the invitation to camp in his spacious garden and home, where there is so much more than spiders.

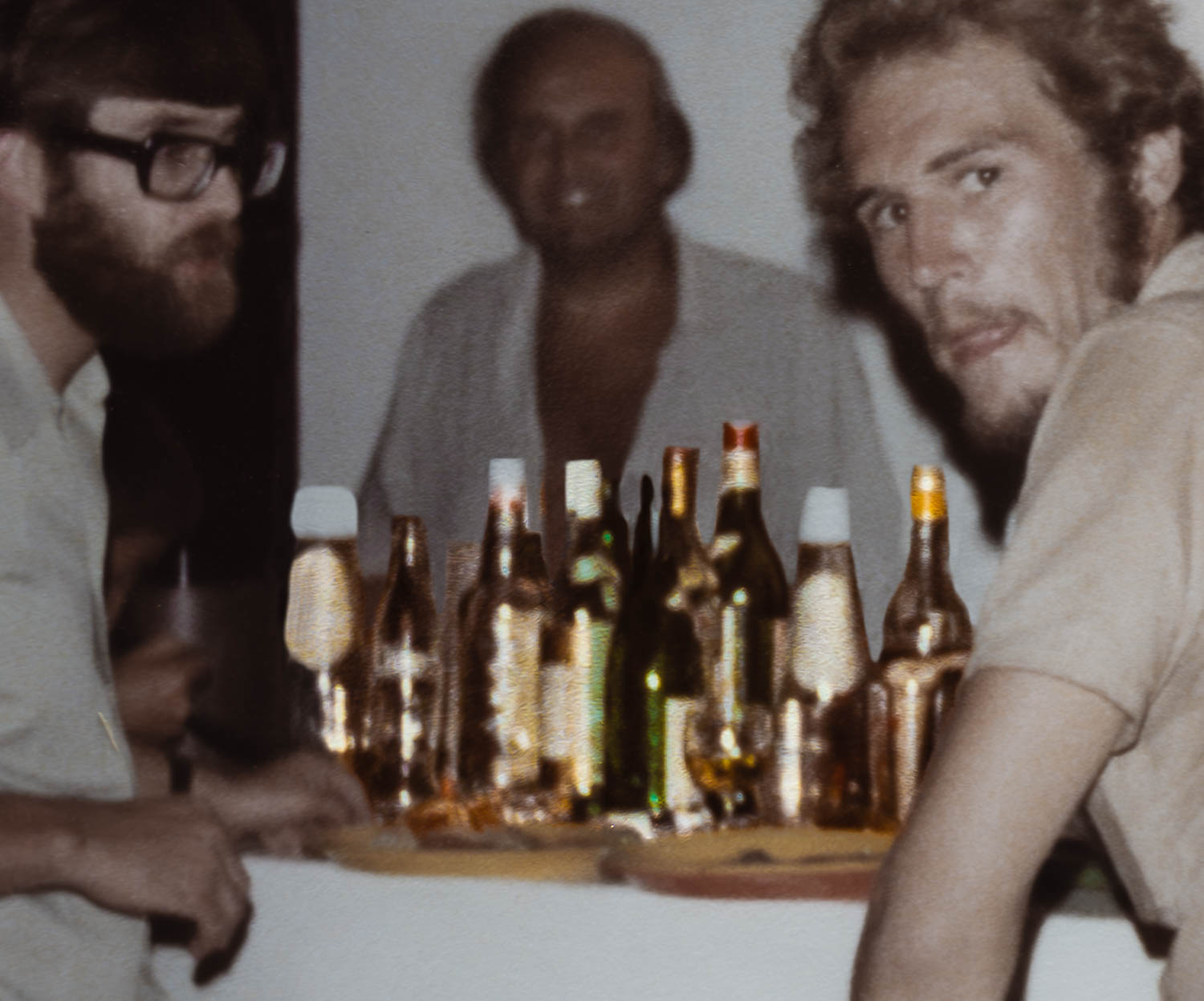

We have arrived in a different Kano. Firstly, there is a big imposing gate. It is wide open. Sitting cross-legged on a mat on the ground next to it is a gateman dressed in the distinctive robes of the Tuareg, and close by is a small gatehouse. Beyond that are the spacious grounds and a large house. We quickly get the tents up and move to the patio. Doug invites some friends, fellow expats, to join the party.

By chance Lynne and I are rostered onto cooking duty that night. What luck! What luxury to have a kitchen to cook in! And what a contrast to the homes of the people in Rhumsiki, and throughout rural Africa. It reminds me of homes I saw in India; one day it suddenly hit me that these people spend their entire lives camping out. A regular kitchen is such a treat after weeks of cooking bent close to the ground, stirring pots over the fire, and I’m so grateful for it.

We move efficiently around the spacious kitchen. Cooking has never been so much fun. It’s still the same food from the truck – our usual, spaghetti and a sauce made from onions, canned tomatoes, those dire canned sausages, and some fresh vegetables, but the preparation of it is a joy.

We eat and party out on the patio.

And when I say party I mean party. Well into the night.

Still, sadly, one of my enduring memories of this encounter with Doug’s generosity is that Brett and Cameron stay up pretty much all night drinking all the alcohol. I don’t mean the truck supply, I mean Doug Lawson’s alcohol. All of it . . . . . . .

This brief encounter with something akin to our normal western lifestyle fuels us for the coming journey. To the north the Sahara is looming. In the extreme northwest of Nigeria we come to Sokoto, stopping as usual for groceries before setting up camp away from the city.

It is from Sokoto that we finally head north into Niger, crossing the border at Tunga Nama just north of Illela. The Sahara awaits.

Next post: Niger – a border crossing manned by convicts, desert nomads, and the first experience of the Sahara.

Disclosure:

1. I’ve changed the names of everyone involved for privacy.

2. Obviously any photo with me in it was taken by another member of the group, but I’ve no idea who. We all swapped photos when we got to London.

Previous posts:

1. The Drums Of Africa. Botswana and Zambia.

2. Tanzania Mania

3. Wildlife And Tribal Life In Kenya

4. The Opposite Of Glamping

5. Turn left At Sudan

6. Mud Luscious and Puddle Wonderful. Central African Republic

7. Becoming Unstuck. Central African Republic

8. Waiting For The Rabbit To Die. Bangui, Central African Republic

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

Enjoying reading your adventures. So much to know

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Indra. I’m glad you’re enjoying them. It was such an epic journey, and good to finally share it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

A bit of culture shock I imagine, cooking in that modern kitchen. And what a contrast from the stone huts with grass roofs. Further showing the division between rich and poor. Another great chapter Alison! Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Maggie. Huge difference between rich and poor, though I think, back then anyway, the people in the villages in Cameroon were doing ok, a really simple life, but well enough. On the other hand there was definitely a vast difference (and still is) between the rich (especially rich white) and poor in Kano, and pretty much throughout Africa.

That kitchen was culture shock in the best way!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been looking forward to each new chapter in this journey. I wonder how much of what you saw would be different today. I’m sure it would depend on the area and things like war, drought and famine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks you so much Julia. I’m glad you’re enjoying it. I think quite a lot would be different today for all the reasons you said as well as corruption. And the internet, and cell phones, which have changed so much throughout the world. Rhumsiki is apparently a tourist destination now. I think we saw the beginnings of that.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The real kitchen made me laugh. We had that experience in Kigali, Rwanda. What a luxury.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a luxury! And I was so lucky that I was rostered on that night.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alison, how lucky you are to have seen such a fascinating corner of the planet. The Mandara Mountains with Mchirgué and nearby Rhumsiki look spectacular! I wonder how these places are like today. How nice that your group got to meet Doug and camp in his garden — I imagine that must have been a nice little luxury after roughing it for such an extended period of time. When I read about what you saw in Maiduguri, that name immediately reminded me of the news I watched years ago about the insurgency and violence that rocked this part of Nigeria. I wonder what happened to those kids in your photos.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Mandara Mountains area is truly spectacular. From what I’ve read Rhumsiki is much more touristy now. I was a bit when we were there, and rock climbers have always been drawn to the area, but apparently it’s much more so now.

Meeting Doug in Kano was such a gift. We were all more than ready for a little luxury.

Nigeria has been pretty unstable for sure over the past decades. We were lucky to have gone there when we did.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oooh, mountains! And sky! It is refreshing to see these pictures now in your post; I can only imagine how delightful it was to see them after weeks in the jungle. It does make you appreciate them in a new way! Peter and I are having that experience now, having moved (finally) to NY and it’s just different than Oklahoma – everything is so PRETTY!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was such a relief to finally get out of the jungle. And then to mountains! It helped revive us all. How wonderful for you two that you’ve finally moved to New York. It sounds like it was quite a time in the making, and that it was worth the wait.

Alison

LikeLike

Another great chapter, Alison. I can picture you scurrying around in a real kitchen after all of your days cooking over a campfire. I thought your photo of the Mandara Mountains and Rhumsiki classical. Again, I can’t help but feel a bit of nostalgia for Africa and its people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Curt. Oh that kitchen was such a treat! Thanks re the photo. I have no memory of how I managed to get that photo. Doing these posts I’m constantly frustrated by how little I remember, and wishing so much that I’d made more notes.

Alison

LikeLike

Photos are always great for jogging memories. At least that’s how it works for me. In terms of my Peace Corps experience, I had quite a few photos, but the real aid was that I came back and recruited for Peace Corps for three years. There was plenty of opportunity to tell my stories. Over and over. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

In a similar way I remember far more about our travels that Don does because of editing the photos, and doing all the researching and writing for the blog posts and in that way living it twice.

LikeLike

Same here, although Peggy does edit my posts. I also have my daily journal going back a quarter of a century. 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems traveling has gotten a bit easier, although maybe not easy. A respite in a place with a kitchen. But it’s mindboggling that there are 200 ethnic groups, and a sacrifice room??

LikeLiked by 1 person

Travelling definitely got easier once we were out of the jungle and therefore onto relatively good roads. And the kitchen was obviously a huge treat. I too found the 200 ethnic groups remarkable. I think I read that in Britannica – and it took me hours of research to establish that the really pointy huts are the Mafa houses. There are quite a few pics of those very pointy huts online but are just labeled Cameroon.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a learning experience that trip must have been.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was, in so many ways. But must admit that I’m doing now most of the learning about the people and places as I create these posts. I think we were just too bound up in making forward progress to do much research about where we were. At the same time I’m a bit amazed at my lack of curiosity at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a different perspective that comes from maturity as well, I would assume. I so regret not asking my grandmother, who lived with us, about her story, how and why she came to this country, etc. It never occurred to me until I was much older and it was too late.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, I know exactly what you mean about the perspective that comes with a little maturity, and how we start to see things differently. And like you, I really regret not asking my parents more about their lives. I so took them for granted. I suppose all children raised in a relatively stable household must do so. Still, I’m now so curious about their lives before me and my siblings, and of course it’s too late.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Goes to show how easy it is to take modern conveniences for granted. Just go without for a while…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, so true. I realized that many people – in Africa, in India, and I’m sure in many other places in the world, basically spend their lives camping. We lucky privileged few get to have electricity, and water from a tap, and all “mod cons”. I love camping. And I love going back to “civilization” again afterwards.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is such a lovely travelogue, Alison. There is so much to know. Enjoyed a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Indira. I’m glad you enjoyed it. It was such a wonderful creative project for me to finally blog about my time in Africa all those years ago.

Alison

LikeLike