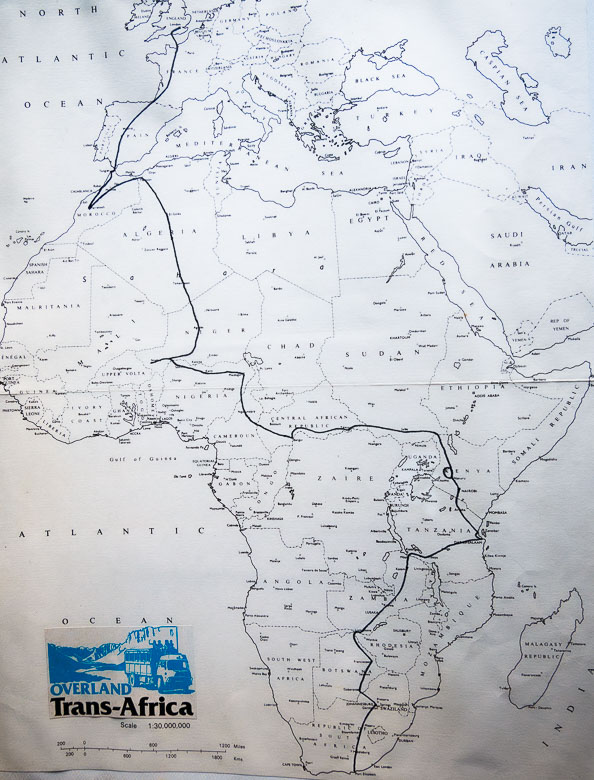

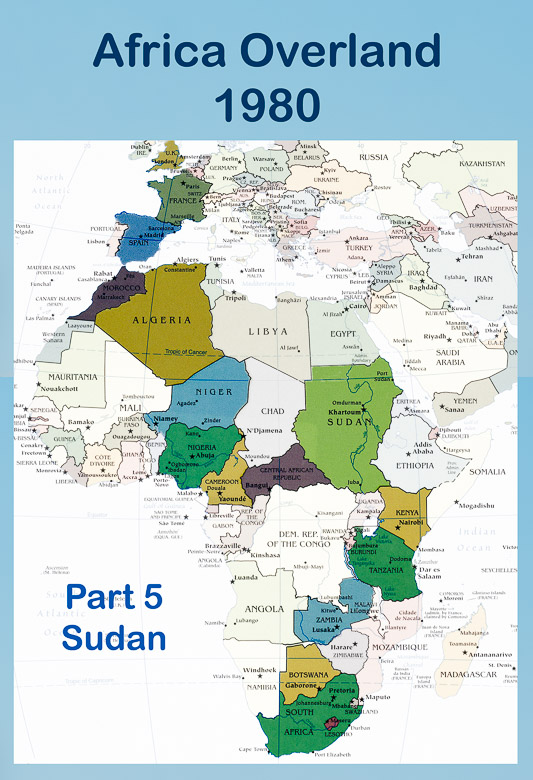

This is the fifth instalment of a four-month trans-Africa trip from Johannesburg to London that I did with Exodus Expeditions in 1980, travelling by ex-army truck and camping. We were not sightseeing, though we did see some incredible sights. Our goal was to see and experience Africa from south to north by whatever route was open. Four months. Twelve people. One truck. Fifteen countries. 18,000 kilometres. Links to the earlier posts are listed at the end of this one.

*****************************

The days are long hot thirsty bumpy dusty monotonous crabby tiring uncomfortable, the truck continually bumping and swaying, the crates of beer and coke slide up and down the aisle, we get on each others’ nerves, we are all lethargic. The heat is vindictive and incessant. We are always filthy. It is only two days since Eliye Springs and the beach at Lake Turkana and already I dream of it. This is like some form of torture. Maybe I’m a masochist. I wonder why I am here . . . . .

I know now why I am here. We finally stop to camp, the sun nearly down, the cool of the evening coming, and I wander off into the scrub with a bowl of water (my precious one litre ration allowed for washing) and sponge off the worst of the dirt. I wander back to camp. No cooking or washing-up duty tonight.

The desert is criss-crossed by dry river beds known as luggas where there is a greater profusion of trees and shrubs. We are camped in one. Us and the mosquitoes. They are a menace for the first time. I sleep outside on my camp bed and christen my new mosquito net, tucking it in all around underneath. There’s a soft breeze. Here in this largely uninhabited part of the world, after everyone is in bed, the darkness is absolute. All is well. Sleep comes.

*******************************

These days it’s extremely dangerous to drive in South Sudan due to armed robbery, violent attacks and poor driving standards. Most roads are dirt; narrow, rutted, and poorly maintained. Very few are surfaced, particularly outside Juba, the capital, and in 2024 South Sudan remains in a serious humanitarian crisis. Political conflict, compounded by economic woes and drought, has caused massive displacement, raging violence and dire food shortages.

Except for the roads, which were indeed unpaved, narrow, rutted, and neglected, it was a different story in 1980. Since Sudan first gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1956 there have been only eleven years of peace. The clash of cultures, religions and ethnicities has led to nearly fifty years of civil war. Somehow we hit the sweet spot, if you can call it that, between a time of uncontrolled violence and war, and relative peace. Another civil war began in 1983.

Possibly the frustration and anger the people were feeling is quietly seething underneath, but we really have no idea what we’re driving into; perhaps Craig, our leader does, but we’re blissfully ignorant of the possible dangers. And we experience a Sudan that is difficult travelling, but affords us some lovely experiences with the people who live there.

Driving northwest from Eliye Springs, soon after Nakodok in Kenya, we cross the border into Sudan. We avoid Uganda, then ruled by the insane and insanely cruel Idi Amin. South Sudan as a separate country does not yet exist. If we are to cross Africa, Sudan is a safer choice than through Uganda.

From the border we follow the winding dirt road west, always west, towards Central African Republic. The road winds a little north to Kapoeta, then dips south to Torit, then gradually north again to Juba where we stop for a rare meal out. From Juba north still, to Mundri, and then the road dips south again to Maridi, and further south to Yambio, and then turns north again, skirting along the border with Zaire, until finally near Ri Yubu we cross into Central African Republic. For all the north and south turns of the journey, our direction is west, always west. We are heading across the deep heart of Africa all the way to Cameroon when we will once again turn to face north, our goal being Spain and finally London.

Our first stop in Sudan is just past Kapoeta, about six or seven hours from Eliye Springs. Still daylight, we get camp established – tents down from the truck and erected, tables out, get a fire going, dinner prep under way. It is all routine by now. We create an enclave, a home for the night. Our bulwark is the truck, though we do not think of it in those terms. The tables are alongside it, tents spread around. Dark has fallen by the time dinner is served. It is rice, some vegetables, and those dire canned sausages. By now it is what we’re used to. There are no complaints, just the camaraderie of sitting eating together around the campfire in the dark in the middle of nowhere.

We have passed by villages during the day

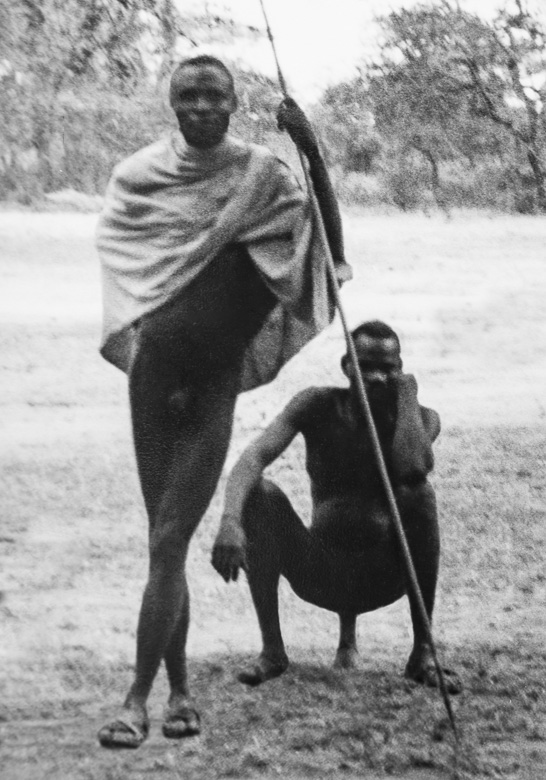

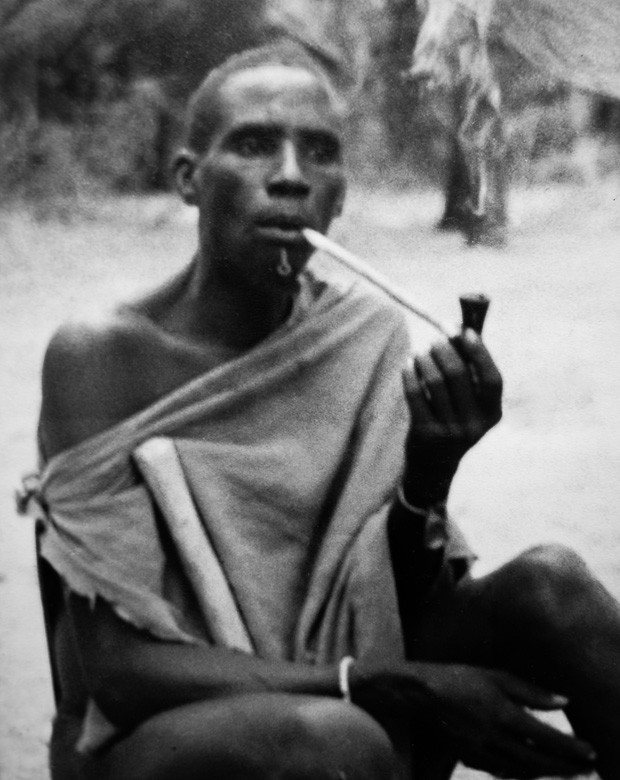

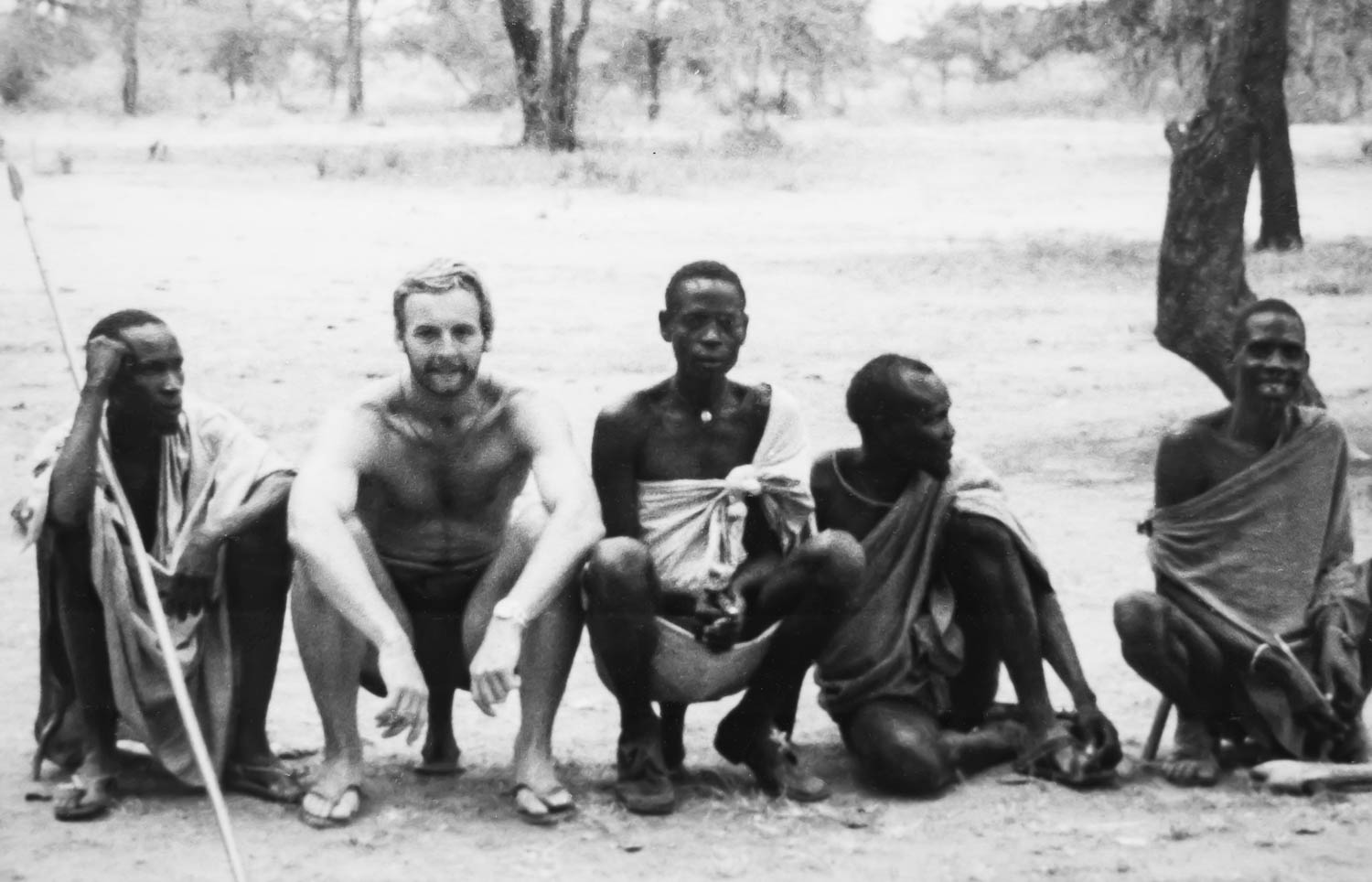

but we are a long way from any of them now. Or perhaps not. Suddenly, quietly, a man, clad only in a tall spear and a piece of cloth strolls alone into camp. He is unabashedly naked; it is normal for him. We all smile and welcome him and he joins us, sitting on what the Turkana of northern Kenya, call an ekicholong. We don’t know whether or not he is Turkana, though probably not, this far into Sudan. Either way the stool is the same. It’s a small carved piece of wood used as a simple chair to avoid sitting directly on the hot desert sand, or as a headrest that helps keep their head off the ground and protects ceremonial head decorations. We offer him a little food which he politely accepts. We are all quietly enthralled, enlivened by this unexpected and authentic connection. Somehow we manage to communicate. He is curious about us, though what is most apparent is his quiet dignity. We are visitors in his land and he’s come to see who we are.

We notice that soon after eating he walks a little way from us to some nearby bushes and vomits. It’s not surprising that his body has a reaction to our food, ejecting it almost immediately. It is so foreign and processed; to his body it is poison.

Soon he takes his leave, and one by one we go to our tents and turn in for the night. Next morning, as we’re packing up, he returns with some members of his tribe.

Steve trades some personal items for a spear. He stows it in the long storage bins under the seats of the truck. I wonder if he still has it. I remember at one point he had it carefully sawn in half to get it through one customs point or another with the idea that he would have it rejoined once he got it home.

My heart does a little dance at the beautiful bead work on one of the girls’ skirts. Carefully stitched onto the leather in an organic pattern following the natural lines of the animal skin, I love the inherent thoughtfulness of it. There is no artifice here, just a simple conversation between beads and fabric. I want to trade her for it but can hardly ask her to take off her skirt.

Somewhere near Juba we eat out. It’s a memorable meal.

We drive to a bar and restaurant almost beyond the outskirts of the city for this rare treat. It’s such a welcome relief from our usual camp routine. We all pile inside and order food and beers. I have no memory of what we eat, only of what happens afterwards.

The building is long, low, and dilapidated, and sits on one side of a wide open space where we park the truck. We take turns staying with the truck; we would never leave it unattended in such a place. Off to one side is a western-style house. There’s nothing else around.

One by one we knock on the door of the house. There are two men there sitting comfortably having a quiet conversation. We politely ask if we can use their bathroom. It is an emergency. One by one we race down the hall reaching the bathroom just in time. Our bodies eject that food from both ends as quickly and forcefully as it can. What luck that that house is there, and that those men are so kind and accommodating. We are all drained. Literally. That’ll teach us to eat out. As best as I remember it is the only time any of us gets sick during all four months in Africa.

We continue heading west. Mosquitoes bug us in the evening and insects blow in on us all day. Sometimes there are quiet times to nap. There’s a net bag in the truck. I don’t know how it came to be there. No one seems to own it. Perhaps some kind of dry bulk food came in it at one point. Anyway it is stiff netting, not soft and floppy like a mosquito net. One day I see it and pull it over my head so I can nap without the insects and mosquitoes bugging me. It works.

From Juba it’s two more days travelling to the border with Central African Republic. We pass villages,

and one night camp in a “church” carved out of the jungle. There’s a makeshift altar and logs for pews.

The further west we go the more we leave behind semi-desert and enter into the central African jungle. Here is the steamy tropical fecund land that encircles the earth at the equator. The road begins to look like this:

It is a harbinger of things to come . . . . .

Next post: the first of two about traversing Central African Republic and conquering the central African jungle. How do you spell mud?

Disclosure:

1. I’ve changed the names of everyone involved for privacy

2. Obviously any photo with me in it was taken by another member of the group, but I’ve no idea who. We all swapped photos when we got to London.

Previous posts:

1. The Drums Of Africa

2. Tanzania Mania

3. Wildlife And Tribal Life In Kenya

4. The Opposite Of Glamping

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2024.

So sad that the fighting goes on, Alison, but they were memorable times for you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know! South Sudan seems to be a mess in so many ways. I did watch a video of a man driving from Torit to Juba (the most travelled section of the east-west road) and it’s been fairly recently widened and graded and seemed relatively safe, but I think relatively is the operative word. None of the overland trips go there now, or into Central African Republic which is as bad or worse. Truly two of the world’s saddest trouble spots for sure.

Definitely memorable times for me. I look back and am amazed at what we did.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read your comments on being there at a relatively calm time and I immediately thought of Liberia and the hell it was destined to go through, Alison. We were there at a good time, as well. But the danger was on the horizon, almost inevitable. There is something magical about your tale, magical about Africa that I tried to capture in my book. Good job. I continue to read holding my breath. –Curt

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Curt. Looking back, and at the time as well, it felt magical. I don’t know how we did it. And that was the magic – that we did it, that somehow there was this overarching destiny that got us through. Same for your time in Liberia. And yes Africa itself – truly magical. We were both so lucky to experience those countries when it was still possible. There seems to be so much anger concentrated in parts of Africa, and there doesn’t seem any way to heal it.

Alison

LikeLike

“There seems to be so much anger concentrated in parts of Africa.” My major at Berkeley was in international relations but it was focused on Africa, Alison. Africa seems like a tragedy that just goes on and on. Colonialism, tribalism, and international politics all played their role it seems to me. So sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, so sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah memories of the Sudan. I travelled overland from Aswan to Juba in 1977. My transport was a combination boat, car, camel, bus and finally barge through the Sud. Along the way I traded a bottle of nail polish for a bone bracelet. I loved listening to the drums at night. When I returned in 2009, the drums were silent except for one night.

LikeLiked by 1 person

OMG Peggy, your journey sounds epic, especially back then. It must have been amazing.

We hardly heard the drums after that time at Kalambo Falls.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really love the connection you and your travel mates made with the locals in South Sudan. It started with their genuine curiosity of other humans who look and dress so differently from them. I wonder if we can still experience such thing these days when smartphones and the internet have penetrated even the most remote corners of the planet. I love the idea of bringing an ekicholong when traveling to places like this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was really amazing meeting those people. It was completely unexpected, and so genuine. I’d be astonished if anything like that would happen today; the world is too connected as you say.

Thos ekicholong are very clever little devices for sure!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

How wonderful that the two worlds could come together in such an open way, new to each other. Indeed, hard to imagine in this day and age. Thanks for letting us sit with you and the group in the truck and around the fire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a really amazing experience. The whole Africa trip was amazing. Looking back on it I’m completely gobsmacked that we did what we did. This encounter in Sudan was so special. And you’re right, with the internet and cell phones everywhere now it would not be possible today.

Alison

LikeLike

Your wonderful post and incredible travel photos are certainly worthy of being included in between the National Geographic magazine pages, dear Alison, especially meeting the tribe! Such a fantastic cultural encounter – we are losing Indigenous communities due to the pressure from the outside world for their land and resources and it must have been amazing to meet them. Thanks for sharing, and have a good day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Aiva for your lovely compliment. Meeting that tribe was a really special experience, and sadly would not likely be possible now. There is so much unrest in that part of the world now it’s heartbreaking.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had to wait until I had enough time to sit down and read this properly. You really were in a National Geographic experience that most of us will never have. It’s a good thing you described the stool otherwise the first black and white picture of the two men may look like something else 😊! I’m really enjoying your stories Alison. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Maggie. I’m still amazed by what we did.

Lol, I had a chuckle about your comment about the photo of the two men! Those stools were so cool – small, light, and practical (though I can imagine your butt getting a bit sore from the hard wood after a while).

I’m glad you’re enjoying the Africa stories. It’s a huge rich creative project for me to go back through all the photos and memories and put it all in the blog.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure it’s a lot of work, but also fun to go back into those memories. It’s appreciated 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤗 🥰

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an adventure … even the names of the places you went are so exotic and compelling. For me, Sudan has always conjured up danger even though I was alive when brief periods of peace reigned. The idea of traversing it gives me shivers of both fear and excitement. I’ve been lucky enough to see many of the places that piqued my imagination decades ago and fortunate to see many parts of Africa as well, but I think my chances of ever visiting Sudan are pretty much gone. So cool that you did this trip at a time when such things were possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We were so lucky with timing, both for Sudan and Central African Republic. CAR had a coups in 1979 and 1981, and we were there in 1980!

I know what you mean about it being exotic and compelling, and we saw only a small part of Sudan. Looking back I can hardly believe what I experienced, and I wish I’d made more notes. Instead I’m relying on memory – so much has been lost, but more bits of memory come back as I look through photos. Most of the mundane has gone, and I didn’t pay nearly enough attention to our connections with the people, even just in the markets. Travelling when you’re young! It’s so different from how I’d approach it now.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating experience! I’m so glad you are sharing it with us. I love you sleeping under the net.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Darlene. I’m so glad you’re enjoying it. I’m having so much fun putting the posts together, and sharing it all. It definitely feels a bit like reliving it, and I’m amazed by what we all did.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Continually amazed at the pictures of African villages and people. Africa wasn’t a big focus by the time I started to pay attention to what my parents were watching on the news (the first Gulf War) and it is a different view to go back in time to 1980. Their skin is so very, very dark!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was a different time for sure, and we were incredibly lucky to get through Africa at the time that we did, not just in Sudan, but also in Central African Republic.

I would not take these photos as indicating any accuracy as to skin colour. They’ve been sitting in a scrap book for 40+ years and have become both very faded and discoloured. It’s taken a lot of editing for me to resurrect them, and I’ve been more successful with some than others. From what I remember the dark brown of the women is more accurate than the black of the men in the opening photo.

Alison

LikeLike

Incredible post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jadi. It was such an amazing time.

Alison

LikeLike

You were fortunate to see what you did of Sudan during a somewhat peaceful time. But I was most struck in this story about the food that made the native man sick, and the native food that made you all sick!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We were lucky for sure to see some of Sudan. At the time it was the better choice than Uganda. I think our food made the local man sick because it was so processed, full of chemicals. We didn’t have native food so much as we just got food poisoning from food prepared unhygienically.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

That makes sense – a good analysis of the food reactions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is heartbreaking that South Sudan is still at war even after gaining independence, and now the rest of Sudan seems to be enveloped in strife as well. How lucky you were to have passed through during a time of relative calm.

There must have been so many moments of unscripted magic — thank you for sharing that serendipitous encounter with the local man and other members of his tribe in both words and photos. The part where Steve traded some items for a spear made me think about what I’d have done in his place. An ekicholong seems like a much more practical memento, being that much smaller and easier to get through customs!

PS I wonder if four months of subsisting on canned sausages put you off them for life…

LikeLiked by 1 person

We were so lucky to have been able to see some of Sudan! And Central African Republic too. Not surprisingly none of the overland trips go through the centre of the continent now.

Having that man wander into camp, and then come back the next morning with others from his tribe was pure magic!

I’ve never eaten canned sausages before or since 😂 – I can’t even imagine! Though of course this somewhat speaks to how privileged I am that I don’t have to.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person