Icon: A person or thing widely admired especially for having great influence or significance in a particular sphere.

Australia 1968 – I left home at 17, all mad eagerness, invincibility, and naivety. I moved to The Big Smoke, freshly graduated a year early from high school. My sister and her husband lived in Darlinghurst in an iconic Sydney-style Victorian house, long and narrow and reeking of genteel dilapidation,

and they invited me to live with them. Julie was working at the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, now Opera Australia, in the wardrobe department making costumes for Turandot. She got me a job there as assistant to the milliner. Soon I moved from Darlinghurst to join another sister in her bedsit in Bondi, with frequent walks to that most iconic of Sydney beaches.

As part of a whole collection of Sydney coastal walks, there’s a six kilometre walk from Bondi to Coogee. Bondi Beach to Tamarama Beach is the first short hop. It’s a concrete-paved, steel-railed easy walk from one beach to the next. Back in 1968 it was little more than a bush trail. We’d wander along towards Tamarama, and when the tide was out we’d clamber down and sit in the sun and eat fresh naturally grown oysters straight off the rocks. We took for granted the million-dollar views.

Then we decided since there was two of us we could afford a bigger place so we moved to an apartment in King’s Cross, Sydney’s iconic red light district. It was far from genteel, but it surely was alive, especially at night. Then Suzanne moved to Melbourne, so I found a bedsit across the water in Neutral Bay. I don’t remember what moved me, but I then abandoned the bedsit for a flatmate in Crows Nest after answering an ad in the paper. I lived in five places in 15 months. How do I say I was unsettled without actually saying I was unsettled?

But I was fearless. At least on the surface. And I got to know Sydney, and rode the iconic green and yellow ferries

all over the iconic harbour.

I had my motor bike shipped from Canberra and thought nothing of riding to and from work across the iconic Harbour Bridge, known locally as the Coathanger.

The iconic Opera House was only partly built; the iconic sails were a distant dream.

None of it was iconic back then. At least not to me. Probably not to any of us. Sydney wasn’t much on the tourist radar. Few people knew about it, and those that did thought it was Australia’s capital. To me it was just Sydney. The Big Smoke. A whole new adventure, and I made the most of it.

When I worked at the Trust I’d go for drinks after work with my co-workers to a wine bar called John Huey’s. It was down on The Rocks, a now iconic area with the oldest original buildings in the city; in the country actually. These days it has an open-air market, upscale restaurants, a museum, buskers, a touristy liveliness. Back then it was kinda dilapidated, low key, a bit boring really, except for the pubs, and Huey’s.

I got a job serving drinks at Huey’s the first or second night I went in there; it was packed and they were short staffed. Great live music and free flowing wines and cider; it was the place to be. Never mind that I wasn’t old enough to be in there, let alone work there; people weren’t much carded in those days; actually, cards didn’t exist. When my temp job at the Trust ended my job at Huey’s expanded to include lunch-time waitress serving spag bol or hero sammies to the always busy lunchtime crowd.

When a knock came on the door pre-lunchtime opening John Huey would ask us to say he wasn’t there while he hid in the bathroom; the taxman I think. I don’t know if he was ever caught. The wine bar doesn’t exist anymore, but it sure was iconic in its time.

After 15 months in Sydney I returned to Canberra to be a “good girl” and become a librarian. Being a “good girl” and librarian lasted until my first extended trip out of Australia in 1974-5. On my return to Australia I went to art school, a much better fit, but left after seven months to go work in a bar in an isolated desert mining town to make money to travel.

So anyway, in December of last year, during our most recent trip back to Canberra, my niece says she’s going to Sydney for the day to buy some fabric and do we want to come? I’ve driven that highway between Canberra and Sydney many times, long before it looked like this,

but never just for the day. Whatever. It sounded like fun.

First stop is Glebe Markets*, a weekly pop-up market in one of Sydney’s hip inner suburbs. We dive into the crowds

looking for Christmas gifts and lunch. Crystals, handmade jewellery, new clothing, vintage clothing, new vintage-style clothing, plants, hats and bags, gold-plated natural freshwater pearls, bread lamps made from real bread (?!), some truly awful fluorescent “spiritual” paintings, handmade pineapple soap, tie-dye, boho, retro, alternative, up-cycled and re-worked. And food from all over – Chinese dumplings, Indian curries, fresh juices. And along with the crowds eating lunch on the lawn

are the inevitable bin chickens, above in the trees,

and picking through the rubbish bins. I’ve written previously about bin chickens, the Australian white ibis. With daunting adaptability they are establishing colonies in the cities. There are an estimated 90,000 ibises in the Sydney area alone, twice as many as in their shrinking natural inland habitat.

Perhaps I’ve not fully absorbed that time I lived in Sydney as a teenager, perhaps not fully understood the effect it had on me. Driving into the city, and then into the inner suburb of Glebe, I’m entranced by the terrace houses. Or perhaps I just enjoy vintage inner-city charisma that’s uniquely Australian, but seeing them feels like a homecoming.

Many of the streets of Glebe are lined with Victorian-era terrace houses, and single-story workers’ cottages dating from the 1850s to the 1890s, coinciding with the gold rushes. The floor plan of the terraces was a direct copy of those found all over Britain. The distinctively Australian balconies came later, a nod to the distinctively Australian climate. You can be sure all the interiors have been renovated and that they are now worth squillions.

Suzanne and Ellie go off to find the best button shop in the world. Don and I go for a walk, east towards Haymarket and then north to the Australian Museum. I can’t think of a sea creature more iconically Australian than the shark. And of course there’s a huge one in front of the museum.

We continue walking, past St Mary’s Cathedral,

past more terrace houses, past a bin chicken at a fountain,

into the Royal Botanic Garden,

and so finally to the harbour, where people play on land and on the water; a microcosm of Sydney life.

We want to explore more but we’ve run out of time. Reconnecting with the others we head back to Canberra.

A bit over three weeks later we return to Sydney, this time travelling by bus

past the easy rolling hills, spindly gum trees (probably second-growth after a bush fire), dry grasses, and farms.

It’s a four-day trip to visit a friend who’s housesitting in a completely different part of the city.

We arrive downtown, take a train to iconic Circular Quay, and wait for the ferry.

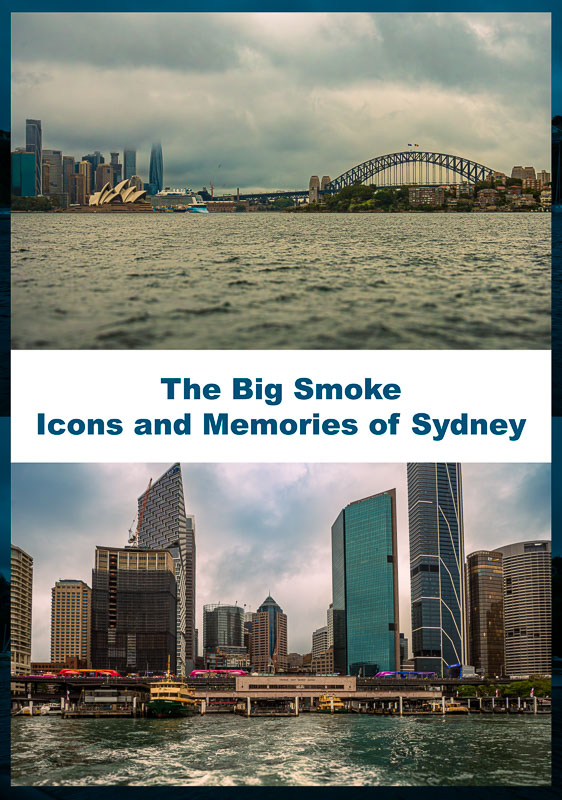

From Circular Quay we can see four of Sydney’s greatest icons in one wide panorama – the bridge, a ferry, the Opera House, and the harbour, Sydney’s aquatic playground.

Getting technical, this inlet of the Pacific Ocean 19 kilometres (12 miles) long, is called Port Jackson, and Sydney Harbour is a part of it. But no matter what you call it the whole convoluted intricate shoreline extends more than 240 kilometres (150 miles), reaching ever inland as a series of jagged peninsulas on both the north and south sides. There are extensive docking facilities, at least twenty unspoiled swimmable beaches, spacious public gardens, areas of natural bush. The inlet, covering an area of 55 square kilometres (21 square miles) is said to be the world’s largest and deepest natural harbour. How do you say iconic?

As for the ferries, they were there almost from the beginning of the British invasion in 1788. Within a year of arriving, a small boat, made by convicts and powered by sails and oars, began making the journey from Sydney Cove inland to the farms at Parramatta. A return trip took a week; today it takes a bit over an hour. On TripAdvisor a ferry ride is ranked #3 of ‘Things to do in Sydney’; 15.3 million customers a year can’t be wrong.

Despite the grey squally weather it feels good to be back in Sydney again, on a ferry on the water seeing all the old familiar places. We look back to Circular Quay, the main ferry terminal and transportation hub,

and chug slowly past the Opera House. I lived in Australia for the entire saga of the Opera House conception and build, and what a saga it was.

In 1956 the government held an international competition; the winner was Jørn Utzon, a young unknown Dane. The projected time of completion was three years at a cost of 3.5 million pounds (or about $7 million). The geology of the site had not been surveyed accurately so the first cost overrun was a massive amount of concrete construction to reinforce it. The building tested the limits of engineering and construction. For a start even as they built it no one knew what the weight of the roof of sails would be. Inevitably as costs and delays grew, tension grew between Utzon and the government. The Opera House became a political football; Utzon was forced to resign, which led to massive public protests. In 1966 a panel of Australian architects was appointed to finish the building. Utzon had absconded with some of the drawings. They still didn’t know what the roof would weigh. At some point the government created the Opera House Lottery to pay for it. After fourteen years, and at a cost of $102 million, the Opera House finally opened for business. Jørn Utzon never returned to Australia. And who can blame him.

The Opera House changed the image of Australia. It was a saga, but we are all enriched by it. Sydney won the lottery, Australia won the lottery, because a few people, over sixty years ago, had the vision and courage to think outside the box.

As the ferry continues its crossing to Mosman Bay Wharf I look across the water under the bridge and see Luna Park! Luna Park is a superbly restored, heritage-listed 1930s amusement park. It is not a Sydney icon, but it most definitely is a personal one. As a child in Melbourne one of our best-loved outings was going to the Luna Park there to ride the Merry-go-round, the ferris wheel and the Big Dipper, and eat pink fluffy fairy floss. I see the gaping moon face entrance and am immediately happy.

Our friend C is housesitting in a big house built up the side of a cliff in the tony suburb of Balmoral.

Quiet dinners at home sharing the cooking, two tiny kittens that melt our hearts and keep us entertained, a friend of C’s visiting for a take-out dinner of fish and chips, lots of good conversation, and a couple of excellent meals at a place called Pasture down at Balmoral Beach,

where C and Don pose in front of one of the huge Moreton Bay figs that line the waterfront.

The weather is not our friend but we walk every day anyway, around Middle Head, exploring some of those trails along the endless harbour foreshore,

and encountering many bush turkeys. Bush turkey, brush turkey, scrub turkey, or gweela, whatever they’re called, they were on the brink of extinction in the 1930s.

The scrub turkey is a very small bird, not much larger than a wild duck, with a breast like a pheasant and flesh as white; in fact I have often served it as pheasant and people have not known the difference. It is a most delicious bird, one of Australia’s finest. Hannah Maclurcan, Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book, 1903.

Since hunting them was outlawed, their numbers have increased steadily, and they’ve now spread throughout the north shore, and recently begun to appear south of the harbour though no one knows how since they can barely fly. They’re beginning to be regarded as a pest. They are not iconic.

This bird is iconic.

The Wiradjuri people call it a guuguubarra, its loud and distinctive laugh is often used as a stock sound effect to indicate an Australian setting, and it’s the only bird I can imitate with any accuracy. The turkeys intrigue me, as I’m intrigued by all wildlife, but the kookaburra lands in my heart.

Memories and icons merge into one. The Sydney of today is different in so many ways from the city I knew as a teenager, but it’s also the same in many ways. The harbour is the same, the ferries, the bridge, the inner suburbs, the botanical garden, Bondi Beach. Despite not knowing the city well, and despite not having lived there for over fifty years, Sydney still feels like home.

*Glebe Markets, after 31 years has closed because the owners want to retire. They are trying to sell the business. There’s another website claiming to be Glebe Markets and offering to sell stall space to vendors. The owners of Glebe Markets say it’s a scam without actually saying it’s a scam. Buyer beware.

Sydney is situated on what was and always will be Aboriginal land; the lands of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation.

Next post: the beach! After two months in Canberra we head to the coast for two weeks at the beach.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2023.

A wonderful trip to the past. Home is always home no matter where we go in this world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Darlene, it was really interesting for me to go back. I have so many places I call home, mainly Canberra and Vancouver. I was surprised at still feeling such a connection to Sydney.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m from the US and have never been to Australia. Your excellent post and pictures make me want to go there more than ever. Your childhood and youth memories are precious. So I think, what could I write about my childhood in Cleveland, Ohio? Somehow, it just doesn’t seem as exciting!

–Julia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Julia. I hope you get to Australia one day. It is a most excellent country 😁 – but of course I would think so.

I really enjoyed diving into and sharing those teenage memories. I have many more!

Somehow, right from when I left home I’ve never been able to live a conventional life. I feel very blessed.

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating life you are leading Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s true. I’ve never been able to live a conventional life (except in brief unsuccessful bursts 😂).

I thank my parents who were ahead of their time, and encouraged us to do what we wanted.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Icons and memories for me too. Visited in 1989

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I sparked some memories. It’s a pretty special city for sure.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading your memories of the big smoke sparked my own. Although I’m living here now I arrived from a few hours north at 20 and lived in Bondi Junction, Queens Park, Paddington then Clovelly before moving overseas for a while…. You covered more of the map – here and everywhere xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I bet it was as amazing for you when you moved to Sydney at 20 as it was for me at 17. And you got around a bit for sure. I was just super restless. Loved it though.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating post… again. Ta.

While the Sydney Opera House was being built, my dad received a call from Australia. He was working for a company that made stuff with titanium and nimonic alloys: impeller blades for jet engines, etc. I believe. The company building the Opera House had redone the figures and found that the stainless steel pins that were to pin the sails together at the base and at the top ribs were not strong enough. They were afraid that, in a very high wind, the sails might either rip apart or, well, sail away. They are now made of one of those alloys… can’t remember which one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Keith, glad you enjoyed. It was a fun one to write.

Wow – I can’t even imagine the sails coming off. What a gob-smacking disaster that would have been. Thank god those figures guys figured out they needed a stronger alloy, and that your dad could find what they needed.

Alison

LikeLike

Such a great post, Alison. I am glad to see you had a great day out in Sydney. I love your photo of the iconic Harbour Bridge – there is just something about the steel arch bridge and how it spans one of the globe’s finest natural harbours. Have you ever climbed to its peak for incredible views? Thanks for sharing – it was an enjoyable read! Aiva 🙂 xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Aiva. I’m glad you enjoyed it. The Harbour Bridge truly is iconic I think. People anywhere would recognise it, a bit like the Eiffel Tower, especially when coupled with the Opera House.

I’d love to climb it one day – even though it costs $300 now 😳

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

A host of memories many of us would love to have, Alison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jo. It was fun to dive into you faraway youth, and relive that time a little bit. Also lovely to be back in Sydney, however briefly.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I saw the Australian white ibis in Sydney, I was intrigued. But when you told me in your comment that people actually call these birds bin chickens, I burst out laughing. I really loved Sydney. I like the fact that it is quite hilly, making it more fun to walk around. I remember waiting for sunset at Mrs. Macquarie’s Chair, and it was magical to see the changing colors of the skies with the iconic Opera House at the foreground. I have to go back and see some of the places you mentioned in this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The bin chickens weren’t there at all when I lived in Sydney all those years ago. I suppose they are another victim of climate change, moving to the city as their natural habitat shrunk, but they’ve sure adapted well to a diet of human food scraps.

I loved Sydney too, it’s such a vibrant city, and has that beautiful harbour.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lovely reconnection with your homeland🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Christie. I enjoyed diving into these teenage memories, as well as my more recent visits.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

When they say there’s no place like home, it’s nice to have more than one place to think of in that way. I had only a brief visit to Sydney, but memorable. New Year’s Eve on Bondi Beach, 1988. (Never try to out party an Australian 😉 )

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can imagine NYE on Bondi Beach was quite something! Oh yeah, never try to out-party an Aussie! 😂

I agree – it’s nice to have several places to think of as home.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderfully entertaining post! Thanks for taking us along on your trip down memory lane. 😘

Surati

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Surati, glad you enjoyed it. It was such a fun post to put together – one of those times when the writing flowed.

Are you in Oz yet, or still in NZ?

Alison 🤗

LikeLike

Auckland Airport – on my way… ☺️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great walk down memory lane, Alison. I now understand better how leading the life of a nomad has suited you so well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Astrid. After leaving home at age 17, the longest I’ve ever spent in one place is 9 years with Don in our Vancouver apartment. Change is my middle name I think.

Alison

LikeLike

It took me two sit-downs to read this totally enjoyable series of reminiscences about Sydney. We have about a week’s worth of memories of the city and its suburbs, but even those make me nostalgic, so I can only imagine the feelings you must have had going back to a place with so big a presence in your past. Super fun to read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lexie. I especially appreciate that you making time to read it, and so glad you enjoyed it. It was a fun post to write for sure.

Sydney’s a pretty amazing city. One day I’ll go back and explore more; all those long coastal walks didn’t exist when I was there.

I think from time to time that I should write shorter posts, that people would have more time for them, but then I get started and the story takes over. This one was originally even longer!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I don’t mind the longer posts! I think part of it this time is that I’m in house-selling, packing, and moving mode, and I’m not allowing myself much time for sitting and reading these days! I loved every word of it and kind of meant it as a compliment that I wanted to read it all no matter how long it took. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s good to know. I had remembered that you’re in the middle of moving. Always a huge stresser and time suck, so thank you! 🤗

A.

LikeLike

What a great trip down memory lane you’ve shared with us, Alison. It is eye-opening to read your childhood stories, and while things have changed – dramatically in some cases – as you say with your words and photographs, there are things that never change for you, making it “home.” The memory you share of clambering down on the rocks and finding/eating fresh oysters reminds me of my childhood on Hood Canal in Puget Sound… those incredible views and experiences of nature we take for granted so easily when young 🙂 There seems to be one trend around the world, which is the gentrification of areas… changing the feel of a city tremendously. What a life you have led! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Dalo, I’m glad you enjoyed it. Much has changed, including a lot of gentrification (which I see happening here in Vancouver too) but there’s enough still the same, enough that still makes Sydney Sydney. That harbour is so stunning. And the beaches.

I’ll never forget eating oysters off the rocks, as I’m sure you’ll never forget the natural surroundings of your own childhood – it seems to me that the world was generally a less frightened place, and because of that we had so much freedom.

I look back on my life and marvel at it. I feel gifted. Without ever consciously deciding too I somehow had the courage to follow my heart, over and over. It led me down some interesting paths. Truly lucky.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison, what an extraordinary life you’ve lived! And how fun to read about your experiences in Sydney as a teenager long before it became a world-famous tourist destination.

Bama and I were there for just a couple days in 2017 and wished we could’ve stayed longer. The harbour, the bridge, the opera house, the Royal Botanic Garden, the Victorian terraced houses – we found it all so stunning. (I do love a good ferry ride so we hopped aboard one from Circular Quay to Cremorne Point to get a different view of the CBD.) What surprised me about The Rocks and the city center was just how *old* many of the buildings were.

It’s strange to think that the Sydney of the 60s was not yet overrun with bin chickens. Coincidentally our first-ever encounter with one was right outside St Mary’s Cathedral – it prowled the lawns looking like it owned the place. And I did not know you could actually visit Sydney on a day trip from Canberra. In my mind they seem pretty far apart!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look back now and realize that I truly have lived an extraordinary life. It wasn’t always easy, but I had no choice really. I was committed to following my heart/intuition without even initially being conscious of it.

Sydney’s an amazing city – well iconic really 😁

There were no bin chickens in Sydney back in the 60’s. I don’t know when they discovered that there were good pickings in the city. I was amazed to discover that there are and estimated 90,000 of them in the Sydney area!

I was a bit surprised that Ellie wanted to go for the day. I wouldn’t do it, but then I’m old, chuckle, and she’s young and has the stamina for it. It’s about 3 hours each way.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

You certainly got around there in your younger days! The Opera House really did put the place on the map for visitors. I went to see whatever it was playing the day I was there. Why is Sydney called The Big Smoke?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did get around, pretty much all my life. Never could keep still for long.

I’ve been inside the Opera House, but only in the foyer. I’ve never been to a show there. I bet that would be amazing.

London is also called The Big Smoke. Toronto too I believe. I think it must refer back to the days of the industrial revolution when factories where belching smoke into the cities. Also in Australia the aborigines referred to Sydney as the Big Smoke.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I go to Toronto pretty regularly – my brother lives there – and I’ve never heard that term, but maybe it’s an older one. When I first moved to Denver decades ago, there were some local terms that have since disappeared. The Valley Highway cut through the city and is now just I-25, and others.

LikeLiked by 1 person