I think there were five or six drums, each mounted on a wooden frame, and the drummers did a precise choreographed dance as they drummed to exactly the same beats. They pounded out the music as if it had been written, which clearly it had, even though the only instrument was drums. I always thought drumming, except for a steady beat for timing, was a more fluid thing, a make it up as you go kind of thing, but what I was seeing were clearly devised and rehearsed pieces. They used their entire bodies to get the most from the huge drums. It was loud and exciting, and I was completely gobsmacked, trembling with the excitement of it, with the power, the energy. And grinning from ear to ear as their joy and passion became my own. Amongst many exciting and heart-stopping experiences of the (sadly now defunct) Frostbite Music Festival in Whitehorse, Yukon back in 1990, the taiko drumming was the most electrifying. I’d never seen anything like it.

My next experience of taiko drums was at the Kurayami Festival in Tokyo in 2018. These drums are seven feet high and are paraded around the neighbourhood on huge wheeled carts. Trembling again.

I fell in love with Japan and all things Japanese on my first trip there in 2018. I’d long known of the Japanese community in Vancouver, and knew that they had annual festivals here, but I’d never sought them out until I returned from that trip. That year Don and I discover the then six-year-old Nikkei Matsuri. Matsuri is the Japanese word for festival, and of course we go to it.

Making our way through the crowds we first go inside the building to see some of the performances on the main stage.

The last thing I expect to see is hula dancing! But given the strong Japanese heritage in Hawaii I don’t suppose I should have been surprised. So in a happy wonder of multiculturalism I watch Canadian women of Japanese heritage dance traditional Hawaiian Polynesian dances. It is Wailele Waiwai, a hula dance group, and their name symbolises endless growth, like a waterfall. In their graceful flowing movements they live up to their name.

The next act, randomly, is Indonesian. More multiculturalism. I’m bewildered, but delighted, especially with the peacock dance. I learn later that the festival partner for that year is Indonesia.

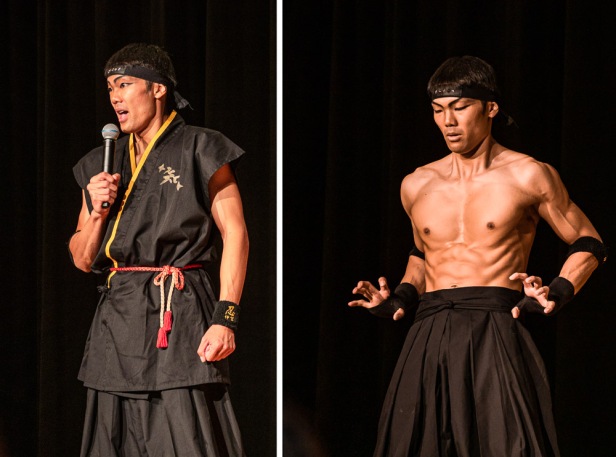

And now for something completely different. I think he looks pretty hot in his ninja clothes, but he looks even hotter out of them.

He’s a real-life ninja who has been training in the ninja arts since he was five years old. The perfection that comes from years of practice shows in everything he does. His stage presence is compelling and we’re hooked from the beginning. Ninjas were spies, and assassins. He has a brown cloaked and hooded adversary who has a couple of long poles to defend himself. The ninja takes him down over and over with knives, with swords, with a long ribbon used to bind his opponent from a distance. It’s spectacular. These guys are trained! And fit! And fast! Back when ninjas were a real thing in Japan they would pretend to be street performers so they could mingle with ordinary people and gather information. So there’s a juggling act with a ball and umbrella, and some audience participation. It’s a really engaging show. We gasp, we groan, we smile, we laugh, and at the end we clap with enthusiasm. Bonus that he’s also pretty to look at. His name is Tomonosuke, from Iga, Japan, and he performs around the world. Worth seeing.

Japan’s loss is Canada’s gain. Yumeko Kon had a dance studio in Tokyo, but she now lives in Vancouver. At Dance Studio she teaches a dance style that is part hip hop, part reggae, part House, part African, and all Japanese! And all fun!

And of course there is taiko!

They are using smaller drums than those I saw in Whitehorse all those years ago, but it’s just as exciting, and just as compelling. This is Vancouver Okinawa Taiko, a taiko group that was formed in 2004. They are as much a performance group as they are drummers, ambassadors of Okinawan style drum-dancing. Their energy and joy is infectious and once again I find myself matching their smiles with my own.

Apart from the main stage performances there’s a game zone, a market place, a yukata dress-up station, a book sale, a Hello Kitty art workshop, and of course a dojo for learning, performing, and viewing martial arts.

Outside it’s a party, a huge crowded communal party

with food stalls like this one serving okonomiyaki

and others serving spiral potatoes, melon pan, Japanese-style crepes, takoyaki, and ramen.

And a beer garden, and dances, and cosplay characters,

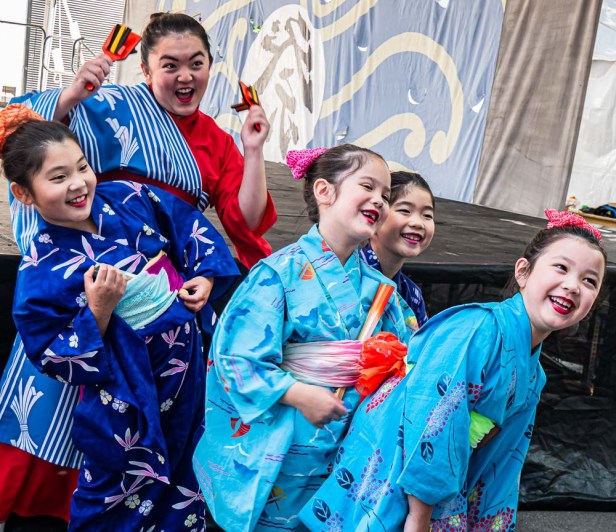

and many people dressed in traditional outfits, travelling back to Japan if only in their imaginations.

The energy is contagious and joyous, a sumptuous celebration of Japanese culture.

*****************************

Her name is Sumiko, and she’s just about the first thing we come to. She’s hard to miss.

Sumiko, the alter-ego of June Fukumura, a Japanese-Canadian theatre artist, is a hyper-kawaii dark humoured clown. Shouting, laughing, cajoling via her microphone she convinces her audience to participate in some quirky games based on equally quirky Japanese TV game shows. There is much merriment happening here on this bright and bubbly August summer day.

Behind her is one of the stages, ahead of her is the main area of the festival. It feels like half of Vancouver is here.

We are at the Powell Street Festival, Vancouver’s other celebration of all things Japanese. And if we ever made the mistake of thinking that things were really happening at Nikkei Matsuri, we find out what a really big festival is at Powell Street. It’s the largest of its kind in Canada.

There are artist talks and panels, a tea ceremony, films, dance performances, a sumo tournament, martial arts demonstrations, singers and musicians, theatre performances, a market place, the chance to try really really big calligraphy with a brush the size of a broom, endless food booths, and, of course! A taiko ensemble! I am happy!

It is Onibana Taiko whose performances are a modern take on a traditional art combining drumming, folk music, and dance. It’s a fusion of shamisen, flute, and kick-ass taiko.

We hear it before we see it. It is the loud rhythmic chant of the men and women carrying the mikoshi and the crowd parts like the Red Sea to let them through. There are many others bunched up on either side, also chanting, ready to take their place as needed to relieve those carrying it; it’s heavy! This is Rakuichi, the Vancouver Mikoshi Group, and Nana Tamura stands on top as those beneath aggressively rock it from side to side to awaken the kami, or Shinto god within.

In the grounds of Shinto shrines there are small wooden “houses” called jinja. It is here that the kami live. The kami are like nature spirits, and once a year they are taken on an outing through the streets – to bless the neighbourhood, and to bring good fortune for the year. They are carried in elaborate golden mikoshi, or portable shrines. The mikoshi is an essential element of festivals all over Japan and seeing it come towards me through the crowd, blessing this Vancouver neighbourhood, I almost feel as if I’m back in Japan again.

After the excitement of the mikoshi we go exploring with the crowd, moving slowly down the street, often finding the spectators as interesting as the performers.

We buy street food. We find a baby sumo wrestler.

And we stop to watch the Ainu performance. The Ainu, an indigenous people who primarily live on the island of Hokkaido, but also live on the Russian island of Sakhalin, are a bit of a mystery. They are probably an isolated Paleo-Asiatic people with no direct relations, and their language does not appear to be related to any other living language. They are a truly unique people, holding on to their culture as best they can in a continually changing world. Having suffered much the same fate as all indigenous peoples when subjugated by a colonial power their lifestyles are widely integrated into Japanese society, but many have sought in different ways to recover their lost culture and tradition. And we get to see something of it on a crowded street on a sunny day in Vancouver. The world really is a small place.

Eventually we make our way back to the stage for the traditional dance performance by Otowa Ryu Japanese Dance Group.

And eventually, sun soaked and exhausted, having followed the festival down Powell Street and around the corner along Jackson Avenue, we fall like rag dolls into a cafe for sustenance, catching this elder as he leaves in all his ceremonial glory.

The Powell Street Festival is held in August in both outdoor locations and indoor venues around the Powell Street area within Vancouver’s historic Japanese-Canadian neighbourhood, on the traditional unceded territories of the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations.

Nikkei Matsuri is held annually in September at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, Tsleil-waututh, and Kwikwetlem First Nations.

Next post: Travelling solo – how I was escorted off the skytrain by police having been falsely accused of racist remarks, and the lessons I learned from this experience.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2021.

When I saw this post, I thought I would be treated with a lot of photos of kawaii-ness in Vancouver, but to find out how multicultural both festivals actually are really warms my heart and makes me miss traveling — and of course, it’s a nice surprise to see an Indonesian dance (this one is from West Java) being performed far from home. We also have an annual matsuri here in Jakarta, but its latest edition was in 2019 before the pandemic. I have yet to check it out but hopefully next year we’ll be able to see it again.

LikeLiked by 3 people

These Vancouver festivals are the real deal that’s for sure. Japanese culture in all its variety is fully on display and some acts (like the ninja, and I think the Ainu) are brought in from Japan for the festival. They were both cancelled last year of course, but things are easing here so they may be on again this year. If the Jakarta one happens go check it out. It might be fun.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is what I miss about Vancouver, the diverse celebrations and cultural events like these. We attended a taiko drumming performance at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre a few years ago and it was mesmerizing. I hope these celebrations will be happening again soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vancouver’s fabulous for festivals – though not quite as extraordinary as Japan, which apparently has 20,000 per year!

I always look for festivals when I’m travelling, but seem to forget about it when I’m at home so I’m sure glad we discovered these two.

A taiko performance in a theatre that big must have been aaaaamazing! So powerful.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alison, what a comprehensive Nikkei festival and equally comprehensive post. Thank you for exposing us to the breadth of this Vancouver Japan focused smorgasbord. The photos are very dynamic and capture the excitement and vibrancy and some terrific portraits in there too. How lucky you are to have that in Vancouver!

Love the Taiko drums. Something very special about those performances and the physical endurance required to master them. Interesting to note that you had this whole condensed Japanese experience in Vancouver but really got to appreciate it after your travels to Japan. Makes sense….

Peta & Ben

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Peta. I’m so glad I managed to capture something of the feel of these two festivals. Both were so vibrant and fascinating – smorgasbord is the right word! I’m really glad we went to them. And of course the taiko performances added to the excitement for me. I think the sheer physicality and passion needed makes it that much more compelling.

I think we get into habits when we’re at home. When we’re traveling everything is fascinating, but at home we get into our usual routines. And Japan was not ever high on the list for me, only as a country I’d never been to before. It was after spending time there that I fell in love with it and looked into the Japanese community here.

Now I’m trying to find festivals held by other ethnic groups. We have a huge Vietnamese community – maybe they have a festival. And for sure next year I’ll be looking out for the Chinese New Year festivals. We have so much at home that gets overlooked.

And since you are there – make sure you take in Guelaguetza Festival in July!

Alison

LikeLike

Such a nice festival! I like the baby sumo and the ladies in the kimono. Two of them even have Tokyo 2020 symbol on their outfit 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both are lovely festivals. I’m glad we went and will probably go again when they resume (probably next year).

I loved the baby sumo – a lucky capture.

I didn’t notice the Tokyo 2020 symbol! Good spotting!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can feel the power of those drums through your writing and photos. Trembling. 🙂 Japan is really so diverse. The Ainu, especially, are so fascinating. Hopefully you can enjoy the festivals this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Julie. I’m glad I could convey something of what it was like to be there for all my various taiko experiences.

Japan is enormously diverse – sumo, ninjas, taiko, geishas, Shinto shrines, and so much more. I feel as if I barely scratched the surface when I was there. I’d love to go to a real sumo tournament one day! And if I am ever back in Japan I’d seek out the Ainu. They are the only indigenous people there and I’m so glad they have somehow managed to retain some of their traditions. I know the Tomonosuke ninja was brought from Japan for the festival. I think the Ainu probably were too.

I don’t know if the festivals will happen this year or not. We’re only just starting to open up a little more here.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those festivals look absolutely beautiful! I have to make a point of going to Vancouver to see them someday 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Both festivals are really quite spectacular. One day for sure you will get to Vancouver. How can you possibly live so close and not come to such a fabulous city?! When everything opens up again, maybe next summer, you can come for a visit.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I did do a layover in Vancouver when moving to Calgary lol. I would absolutely love to visit! It’s just right now, even though my Mum and I are fully vaxxed, we still have to be careful for a while longer. If my Mum gets the Delta variant, it would be more risky

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’re fully vaxxed (ie 2 wks post 2nd) on Jul 11. But yes, still have to be careful. There’s always next summer. I don’t even know if these festivals are happening this summer. By next summer there’ll be a tax for the Delta variant 🙂

LikeLike

Congratulations on being fully vaxxed! A tax for the Delta variant? That’s new

LikeLiked by 2 people

It will eventually become like flu shots and we’ll have a shot every time there’s a new variant. The difference being that with flu shots they’re kinda guessing which variants are most likely to surge for the coming winter and it takes about 6(?) months to develop the vax. Apparently with the mRNA vaxxes they can develop a vax for the any variant in about a month. Don keeps pretty up to dat reading about this stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I have been keeping up on the research too thanks to my Dad. He’s the scientist of the family

LikeLiked by 1 person

xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

I absolutely LOVE taiko drumming! The sound of those drums goes right through you, vibrating and dancing. It’s primal and glorious! I first saw them at a health club where my dojo trained, and have seen them several times since around Portland. Always, always a favorite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I too love taiko drumming; I guess that’s obvious lol. And clearly you know exactly what I’m talking about. Primal is right. At that big festival in Tokyo (Kurayami) my whole body was literally shaking from the energy.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve experienced Taiko drumming in Portland, but I’d guess the local Japanese community is much smaller than Vancouvers’. There are no festivals anywhere near the scale you describe. Yours look like a lot of fun.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh they’re loads of fun! I’m glad we went to them and probably will again when things get going again. I think things will be back to normal by next summer.

I didn’t know there was a Japanese community in Portland. So cool you got to experience some taiko there. Not so cool this crazy hot weather we’ve been having in the PNW!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m embarrassed that I don’t know about this festival in my own city (too much time sticking to the North Shore). I assume it will be on in some form this summer (will look it up). Your dynamic people photos just jump out of my screen–such a fun, vibrant post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Caroline. I love photographing festivals – there’s always so much to capture that’s colourful and interesting. All kinds of people come out of the woodwork 🙂

If you only come over the bridge for one of these festivals this year (if they happen – I don’t know if they’re going ahead or not) I’d recommend Powell Street just because it’s bigger, so more on offer.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The energy and joy rom your photos and descriptions oozes out of my computer. Vancouver and its diversity makes me want to spend more time there.

I also am pleased to see your land acknowledgments at the end of the article Alison.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Sue. Both festivals were really fun to attend. And Vancouver’s diversity is really wonderful. There are Indian festivals that I need to get to, and Chinese night markets in Richmond (that I also need to get to), and Chinese New Year celebrations of course. There’s also a huge Vietnamese population here so I need to find out if they have any festivals too. This pandemic is really getting me to be a traveller in my own city much more than usual.

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’ve captured all of the movement so well! One thing that jumped out at me was how you only thought to seek this out after a visit to Japan … I have done that so many times in the two very ethically-diverse cities I have lived in. I guess I am vaguely aware of “x” cultural festival or streets or whatever, but I never truly venture into it until I’ve experienced it overseas. My loss!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops, I meant ethnically-diverse (although the misspelling might also work in these places! 🙂 )

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Lexie. I knew what you meant, but ethically-diverse works too. Because of my experience of only seeking out the Japanese festivals after I’d been to Japan, I’ve now started looking into Vancouver’s Vietnamese, Chinese, and Indian festivals since we have large communities of all three here. Also First Nations festivals. I bet there are some. I just have to do a little digging.

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

These look absolutely wonderful!!! Matsuri are one of my favorite parts of Japan, and this post really put a smile on my face!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mo. So happy to have put a smile on my face. I loved both festivals – there was so much enthusiasm and joy, and the performances were so professional. I too loved the matsuri in Japan – that first visit when I met you I went to 6 matsuri in 18 days!

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

Loved this! Great descriptions of the arts and matsuri performances of the wonderfully unique Japanese culture. Glad to see those traditions kept alive in Vancouver and Hawaii. As with foods from different countries, it’s interesting to see the spin another culture adds to traditional festivals and dishes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Ruth. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I love that we get to see such vibrant festivals here, that the Japanese traditions are honoured and celebrated.

I wish I’d tasted more of the food! I’ll definitely arrive hungry next time these festivals are held – hopefully next year. (Of course cancelled 2 yrs in a row because of the pandemic 😦 )

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh my gosh so wonderful and your p photos are great. Okinomiyaki is my fav and its so hard to find…no one ever does it in a restaurant. I’ve made it at home but it would be the first stop for me at this festival. I think I will add this to my calendar!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Laureen. Oh you must come once things get going again (not this year unfortunately), and for sure there was okonomiyaki at Nikkei Matsuri. I’ve never learned how to make it but sure remember eating it in Japan. Yum!

Alison

LikeLike

Loved reading about this how funny as in Broome Western Australia they have a Shinju Matsuri Festival every year. When we lived there my eldest daughter was only 3 and she became the princess of the festival. I love all your photos and it does make you feel like your there in Japan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Bree. Both festivals for sure had an authentic Japanese feel to them, and a real pride in sharing their culture.

I had a quick look online at the Shinju Matsuri – it looks fabulous! I’ve never been to Broome, only as far north as Karratha, and I lived in both Dampier and Tom Price way back. Broome’s been on my bucket list for a while now. One day I’ll get there.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an incredible festival. I really can see the diversity of activities and the celebration of their culture come shining through. It would be fascinating to attend and learn more- through the artistry and food. Just another reason why I love Vancouver so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both festivals were a wonderful presentation of the Japanese people of Vancouver and their pride in their culture. Such a beautiful atmosphere – everyone celebrating. I wish I’d tried more food!

And yeah, Vancouver’s pretty awesome. 👏

Alison

LikeLike

That sounds like an incredible festival to experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really was! So many aspects of Japanese culture on display, it almost felt as if we were in Japan.

Alison

LikeLike

Another late comment but better late than never. What a great job you did at presenting the glorious energy and color of these festivals – for performers and spectators alike. As lush as the colors are, I really like the photo of the man leaving the cafe where you “collapsed” with his robe flying open – beautiful! That was a moment! As are so many that you bring your readers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lynn. Both festivals were rich experiences – all the colour and activity, the food and performances. There was so much going on that was interesting I often couldn’t decide where to look, and know I missed quite a bit. I hope they get going again. Powell Street is happening this year but in a much reduced form. Next year maybe . . .

I love your comments, late or not 😊 Thanks.

I had a visit with Hedy yesterday! When the border opens the 3 of us must get together.

Alison

LikeLike