11 March 2020

The trail is narrow, and lumpy with tree roots and rocks, which makes it a continuous negotiation. It rises up on the right and drops down on the left. We’re hiking through a tropical forest on a cliff. Suddenly we hear Don call out. I turn immediately and rush toward him, our guide right behind me. Don is on the ground, in pain, and saved from rolling further down by some small trees. There’s that sinking feeling as my stomach plummets, and images of broken bones and rescue helicopters flash through my head, but Don assures us he’s okay.

Fortunately the trees that save him are not like this:

Don had a minor trip and instinctively put a hand out to steady himself when he noticed at the last second what he was about to grab onto. He chose to fall instead. Good choice! He’s mildly shaken and has lost a chunk of skin from his forearm, but that’s it.

I cannot count the number of day-hikes we have done, all over the world in all kinds of conditions, but never once have we carried a first aid kit with us. I have no idea what prompted me, but that morning before we left I mindlessly tossed the first aid kit into my daypack. Thinking about it now, it seems that it’s exactly this kind of happenstance that we should regard as a miracle. I do anyway. I dress Don’s wound, wrap it up and we continue on with our hike.

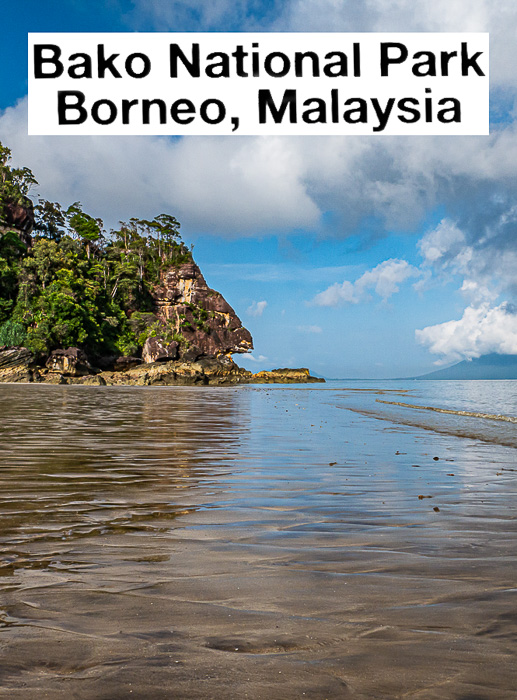

We are in Bako National Park on the island of Borneo in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. It’s the first time in Borneo for both of us.

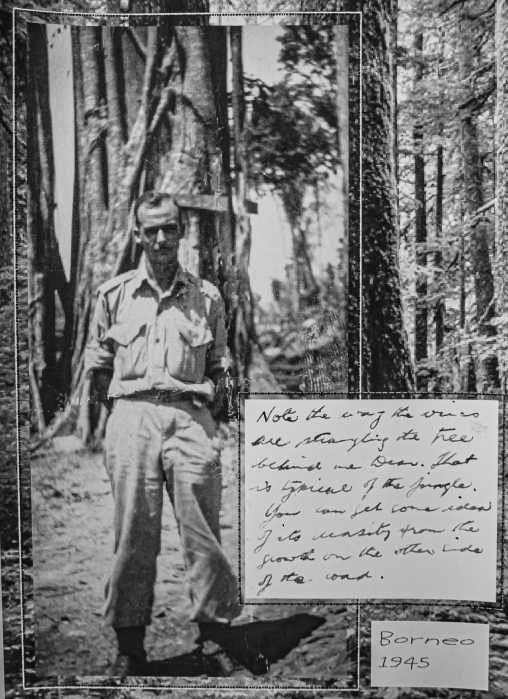

Here’s a little family mythology: my parents were pacifists. Sometime during World War II, one day after work, my dad and his buddy enlisted in the army. Dad announced it to mum when he got home that night. There was, I believe, a bit of a volcanic explosion in our house that night. Mum wasn’t that much of a pacifist. Of course I wouldn’t know anything about it because I wasn’t even a twinkle yet. He was not a combatant, but was involved in logistics, or supplies, or something like that. At some point during the war he got leave and my mum travelled (with my oldest sister, still a baby) from Melbourne to Brisbane to see him. Even today that train journey is over 27 hours. He made jokes about the army custard, which followed him around wherever he was stationed; he swore there was a pipeline to every Australian army base. I think dad was stationed for some of the time in New Guinea. But the point of all this is that I know for sure he was stationed in Borneo. Borneo! As a child it took on mystical, mythical dimensions, probably in part because of this photo:

The original photo is about 2.5×3 inches (6x8cm) and may not even still exist. The inscription was part of an attached letter or on a card. This is a photo of a photocopy of the original photo so whatever clarity there was has long since been lost, but still, there he stands, legs apart, in his army fatigues, in the Borneo jungle. I wonder who took the photo, and how and where and when the film was processed. At some point he received this photo of himself and mailed it to my mother. Note the way the vines are strangling the tree behind me Dear. That is typical of the jungle. You can get some idea of its density from the growth on the other side of the road. If he were still alive I would ask a million questions, but this is all that remains. This, and the way that Borneo, just the mention of it, lives in my heart as this mysterious magical place where my daddy went in the war.

And here I am, finally, in Borneo, and the reality is as magical as in my imagination.

If you take the red public bus number 1 from the town of Kuching after about an hour you’ll arrive at Bako Bazaar on the Bako River. Bako is mainly a fishing village

with the river at its front door and the jungle at its back. Every house has a jetty with boats parked out front, their bright colours shining in the morning sun.

This is a town that lives on the water, ruled by its moods, its tides, its changing depth.

We don’t actually take the bus. We’d read online that the bus goes from the wet market in the centre of town and asked at the hostel how to get to it. We were told we could just go to the bus stop around the corner. So here we are, early morning in plenty of time for the 7am bus. While we’re waiting we take note of prominent landmarks around us – a tall building, a billboard – so that we know when to get off the bus on the return journey. Suddenly a van pulls up asking if we want to go to Bako. It’s more expensive than the bus, but not by much, so we hop in and are on our way. Not only are we ahead of the bus, but travelling faster, and so we arrive quite a bit before everyone else.

Since Bako National Park is only accessible by boat, we’re first ushered into a shed where we buy tickets for the boat ride, then we’re taken to another place to buy tickets for the national park, and then we’re asked if we want a guide for the day (yes), and we pay for that, and finally we are told that because of the tides the last boat will be coming back at 3pm. And then we wait with our guide who introduces us to a breakfast snack of fermented rice wrapped in banana leaf. One bite is enough.

When the bus arrives with more people we all pile aboard the boats and head down the river.

The sun is shining, the sky is blue, the air is warm, the smell of the sea fills the air. It feels like the beginning of an excellent adventure. After twenty minutes, some distance before the river spills into the South China Sea, we arrive at Teluk Assam Beach and the official entrance to the park.

This is a place where rocks, seemingly solid and impenetrable, have succumbed to the persistent power of the sea. Over millions of years the sandstone has been eroded by the waves coming and coming again, and leaving behind them a shoreline of fantastical shapes. The relentless impact of the water has created rocky headlands and steep cliffs, in places coloured bright orange by iron deposits, interspersed with numerous sandy beaches.

Up from the beach, scattered in amongst both grassy and treed areas, there are several low weathered wooden buildings – park headquarters, a restaurant, and various levels of accommodation. Our guide initially doesn’t take us beyond this area. Instead he is immediately engaged in looking for vipers. Clearly he’s done this before, and in short order he finds one. I peer and peer into the bush trying to see it. He knows what to look for, and of course doesn’t want to disturb it, but it is so well camouflaged that it takes me a minute to pick it out from the leaves. It’s small, and highly venomous. I don’t want to disturb it either! It’s a Bornean Keeled Pit Viper. They live in trees and barely move, waiting for their prey – birds and arboreal rodents – to come close enough to become lunch.

Proboscis Monkeys are endemic to the jungles of Borneo, and are now listed as endangered. There are approximately 150 of them in Bako National Park, and our guide says that one of the best places to see them is here, close to all the buildings. Sure enough he soon spots a couple of them up in the trees.

Male Proboscis Monkeys use their fleshy pendulous noses to attract mates. I’ll just leave that factoid hanging there without further elaboration.

As we continue searching for monkeys suddenly our guide points out a wild pig. It’s the ugliest pig I’ve ever seen. This is not your cute pink farmyard pig. Nor does it even have the questionable appeal of the Vietnamese pot-bellied pig. It’s big and brown with tiny eyes and a grotesquely long hairy face ending with a fleshy pink snout. The Universe was not handing out the pretty on the day it created this animal.

We watch it amble into some low bushes and flop down in a puddle of mud.

It’s a Bornean Bearded Pig, and it may not be pretty, but it has a part to play. These wild pigs wander far and wide in family groups foraging for food, and as they do so they disturb the forest undergrowth thereby accelerating the decomposition of organic matter and improving access to nutrients for tree roots. Just as importantly, the Bornean Bearded Pig is highly revered by the indigenous people. The hunting of wild boar goes back more than 35,000 years. Probably because it was so essential to their survival, providing nearly 100% of the meat in their diet, it was believed to be a mediator between people and the spirit world, a deeply venerated animal totem. So, not just an ugly pig after all.

With one last look out to sea at Teluk Assam Beach

we set off on a short hike, initially walking over a boardwalk leading away from the buildings and lifting us above the mangrove swamp near the water. Looking down our guide points to dozens of tiny fiddler crabs. Nature is full of astonishments. The male Proboscis Monkey may have a big nose to entice a mate, but the male fiddler crab has a huge claw! It waves the claw around to show off to the ladies and to scare off the competition. But what I want to know is how does it keep from going round in circles?

These tiny creatures feed off the mud in the mangrove swamps, and dig burrows in the sand up to 23cm (9in) deep. They escape into their burrows at high tide. When the tide goes out they come to the surface again leaving behind works of art as they scatter tiny pellets of sand in a starburst pattern.

Soon we are in the shade of the rainforest. The trail becomes gradually more rocky and uneven. We clamber up and down some fairly steep grades, hugging the side of the hill, all the while looking for more monkeys. This is when Don falls. After I’ve dressed his wound we slow down a bit and become a little more cautious. It’s enough excitement for one day. After about an hour we come to a small, secluded beach.

And now we’re back in a boat

cruising past small beaches, towering bluffs, and fishing boats,

past cliffs worn away at the base creating shaded areas for the fishermen to work,

past the ragged coast where sandstone succumbs to the relentless power of the waves,

until at last we turn around and return to Teluk Assam Beach.

We’re hanging out at the restaurant after lunch, looking out at the grassy area towards the beach when this long-tailed macaque wanders nonchalantly by.

I watch as he walks to a tree, climbs it, and begins to eat.

There is no purpose here, no thinking, no planning, no justification or judgement, just pure awareness, pure survival, pure Life living itself. The moment is drenched in harmony.

It is followed with one of the most interesting and exciting parts of the day for me. Don stays behind, but I follow the guide off into the forest again. He takes me to a small hidden pond telling me that there might be soft-shelled turtles there. I merely follow obediently. I’ve heard of soft-shelled turtles though never seen one, and they certainly were not on any mental list of must-see creatures. And yet, here we are at a small orange coloured pond in a tropical jungle staring at the water. Suddenly there it is!

I had no idea that they would have webbed feet, or that they have sharp claws for digging into the mud. I watch fascinated as it rhythmically lifts it snout to breathe.

As Don says: turtles turtles yeah yeah yeah!

It’s getting late and the tide will not wait. Returning to the beach we gather at the water’s edge for the boat back to Bako Bazaar and the bus back to Kuching.

It’s been a magical day.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2020.

Hi Dear Friend, Great post and My Uncle were living there in Borneo 1960’s. He was a teacher. He shared his stories. So, I will definitely share this with him. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Jeena. I bet it was pretty fascinating hearing your uncle’s stories. I hope he enjoys what I’ve written. I have at least three more stories about Borneo to come in the next few weeks.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, Absolutely right. He enjoyed reading all these. And waiting for the next post. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Because Burneo has kept eluding us, even when we were not all that far, both in Flores and Penang (relatively speaking) I have been looking forward to your post(s). This one had all the essentials of a good adventure in my mind, especially all the wildlife sightings.

I have yearned to see the proboscis (and the orangutan) in real life, but short of that happening (yet) it is wonderful to see your photos and read about your experiences. I actually think the Bornean bearded pig is very cute looking haha. Love the soft shelled turtles.

The photo of your dad from 1945 totally explains your childhood fascination with Borneo …how wonderful that you were able to “follow in his footsteps” and have that connection with him so many decades later! Great photo.

Glad that Don is ok and how fortuitous you took the first aid kit along! Love that type of serendipity.

Peta

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Peta. It was a great adventure, and I’m with you about the wildlife – they are what make this kind of outing so special. We did a journey on the Kinabatangan River and saw dozens of proboscis so I’ll post about that soon. So exciting! And also orangutans in Sepilok.

Just the word Borneo lived in my imagination as a child, and that it was an actual place. As I got older I understood that it was not that far from Australia but never thought to ask him about his experiences there. I was so self-absorbed as a child. Well I suppose we all are to some extent, but now that it’s far too late I’d love to have both my parents back to ask them a million questions about their lives that I never thought to ask when they were alive.

I too love the serendipity of incidents like the first aid kit. I always think of them as little miracles.

Alison

LikeLike

A wonderful report on your adventures in Borneo. It sounds and looks amazing. How great you got to be where your father had once been. I’m for one glad he returned and the result is that you are here sharing your amazing travels. Stay safe!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Darlene. It really was amazing. I’m so glad we went there. When we decided on Malaysia and started researching it was clear pretty quick that Borneo was one of the must-see places. And somehow that place will always live in me because of my dad and that photo. I must have seen it many times as a child and wondered about it. I’m pretty glad he came back too 🙂 so I could get to be a twinkle 🙂 (the fourth one 🙂 )

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

One thing I learned very quickly when I first traveled to tropical places is to always look before you put your hands anywhere. It has saved me from many horrific injuries.

Borneo is one of those places, like Papua New Guinea, which has such an air of mystery about it. I’ve been to PNG, but not Borneo. The mystique doesn’t vanish when you enter.

Wonderful photos, as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Julie. We’d seen trees like that in the Amazon so knew about them, and had had some experience of tropical jungles. It’s really not safe to touch anything – just about anything could either be poisonous, or stab you, or both.

I would love to see Papua New Guinea one day. My sister lived there for a while many years ago. I agree there is an air of mystery about both places. To me there’s something so mysterious and somehow a bit inaccessible about tropical jungles and their indigenous peoples. It feels like a fascinating elusive secretive world that I’d love to explore more.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah Borneo, how I yearn to be back there. Your post has tugged at the heartstrings!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a special place that’s for sure. Perhaps you’ll get back there one day. I too hope to go back.

Alison

LikeLike

Thank goodness Don didn’t grab onto that ‘dagger’ tree while he was falling. The ground was a lot softer, I am sure!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I’m so glad he didn’t! He is too! He made the right choice that’s for sure. His wound took a while to heal, but in the end it was nothing serious, so a much better choice than grabbing that tree!

Aison

LikeLike

How intuitive for you to take along a first aid kit on that day. You really are tapped into something that sees you through some rough patches #blessed

I can imagine the childhood wonder that Borneo evoked, given your Dad’s services there. (Bora Bora was kind of like that for me. My Dad was too young to serve, but Bora Bora was paradise to friends of mine who had father’s that fought in the Pacific). How wonderful to finally make it here after all these years.

Your post has me missing this part of the world very much. We were in Malaysia, and the Indonesian side of Borneo and your stunning pictures bring up so many good memories. Our lives have been filled with little fishing villages and fisherman, so this post is calling me back to SEA

The entrance at Teluk Assam Beach is magnificent with its gorgeous rock formations that tower over humanity.

I adore the images of the proboscis monkeys with their charming faces and an elongated nose. How lucky you are to have seen them. And the soft-shell turtles too!. I would have done a little turtle cheer right alongside Don if I’d been there. Even the pig is adorable, but I would have freaked at the site of the viper

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lisa. Yes, definitely #blessed. I can think of many times when that kind of serendipity occurred. It feels like something is taking care of us, supporting us. So I just say thank you. Sometimes I think thank you is the only prayer that’s needed.

Now that I’ve finally made it to Borneo I do wish my dad was still alive so I could talk to him about his experiences there. But alas he’s been gone nearly 30 years now.

I would love to explore the area more, both Malaysia and Indonesia. We has 8 days in Borneo then had to hightail it back to Canada, and we’ve only been to Bali in Indonesia. I would love to see more of both countries. I too have good memories of SEA, and fishing villages there.

Teluk Assam Beach is quite spectacular, as is most of the coastline there. The cliffs feel both impenetrable and majestic, and yet the waves have their way.

Ah the wild life – always make my day!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again, a fascinating post. Loved the rock formations. Great to co-travel (cyberly) with you two.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Keith. I’m so glad you’re enjoying the blog. Many more armchair travel posts to come 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

Interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It’s a pretty amazing place.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are welcome !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another great fascinating post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love all your photos but especially the last one of the turtle. He seems so surprised to see you there! Lovely story about your dad too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Tracey. I was so happy with that turtle shot! He stuck his head up every couple of seconds or so as he swam around, and then finally he was looking right at me and I got the shot.

I don’t often share much about my family but felt I really had to this time – Borneo was special in part because of dad being there in the war.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading this post brought me joy as I imagined the fresh, humid tropical forest air, the quiet beaches, the playful proboscis monkeys, and those curious soft-shelled turtles. Even though I spent a few years of my childhood in the southern part of Borneo, I have never really explored the island’s dense forests. I’ve been thinking of staying on a house boat for one or two nights, cruising along some tranquil rivers, then followed by a visit to an orangutan sanctuary. Or, climbing some of the island’s majestic cliffs to see tropical pitcher plants. Even just thinking of those ideas makes me excited. Look forward to more posts on Borneo, Alison!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Bama. The jungle in Borneo is quite something, and we’re so glad we went. I too would love to do the kind of adventuring there that you describe. We didn’t see any pitcher plants, but we did do a short river cruise and see orangutans, but a couple of nights on a houseboat sounds magical.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s so beautiful there.

Thanks for your continuing report.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure rabirius. Yes, it’s very beautiful. We’re so glad we went even though we were being told to get home asap.

Alison

LikeLike

A magical day and a magical post! I love this Alison! The story about your dad is fascinating…if only that old photo could talk. I can see why Borneo holds an appeal for you beyond the fascinating creatures and landscapes you saw in Bako. I’m terrified of snakes but I must say that that green viper is a beauty. How did you have the nerve to take that photo? I have researched Bako NP in the past as Borneo has been on our list but hasn’t quite made it to the top. I hope I can convince Mike with this wonderful post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Caroline. It really was a magical day. I’m fairly sanguine about snakes, I suppose because I grew up in Oz and we learned about them from a very young age. In almost all my encounters with them they just scurried away or were busy eating something. It didn’t occur to me to be afraid of it. Now bears in the Canadian wilderness? That’s another story altogether!

It’s funny the way places/ideas/things from childhood that we don’t understand get lodged in our imagination. I had no clue where Borneo was, just that my dad was stationed there in the war and that was enough to make it special.

I have a couple more posts to come on Borneo. We had 3 days in Kuching, and 3 in Sepilok and it felt like weeks – in a good way. I’d love to go back and explore more. Borneo is definitely worth visiting. If you go I’d really recommend staying overnight at least one night in Bako as apparently the best wildlife viewing is early morning.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha…bears, no problem for me! I look forward to your other posts on Borneo and will keep your recommendation in mind. Who knows when we can travel internationally again? I fear our India trip in fall will need to be postponed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wouldn’t be surprised if it had to be postponed 😦 I’m not counting on any travel for at least a year 😦

A.

LikeLike

Looking at your photos, I get cool virtual travels! The photos are incredible! Everything is very accurately noticed! Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much John. What a wonderful compliment. Virtual travelling is about all we can do these days so I’m glad you enjoyed this journey with us.

Alison

LikeLike

The shots of the bay and the karsts are just fabulous, Alison! I can’t conceive that the water level was so high to wreak the damage. Just fabulous! And wonderful that you could follow in Dad’s footsteps 🙂 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Jo. The coastline was just stunning, and I’m glad I could capture something of the feel of it. The cliffs were huge, and ragged, and so richly coloured. I don’t know when the tide gets up that high, but obviously it does. Pretty amazing!

Lovely to get there after my dad was there – wish I could talk to him about it 😦

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

A wonderful trip, Alison. The proboscis monkeys are indeed amusing. And I actually thought that your ugly pig was kind of cute. 🙂 The rock sculpture just above the photo of the macaque is truly magnificent. –Curt

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Curt. it was a pretty special day. Others too apparently thought the pig cute 🙂 We all have our own unique way of seeing things don’t we. Chuckle.

That rock sculpture! Just amazing. Magnificent is the word.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

So right on how we see things differently. Reminds me of all the ugly dogs out there that people have people have specifically bred to be ugly! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yeah! I know exactly what you mean about the dogs lol!

A.

LikeLike

I had a basset hound, once. Ugly enough to be cute. He had a great personality but was stubborn as all get out and the slobber king of the world! Named him Socrates. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember you mentioning Socratese from time to time. Not as ugly as the squashed-face pugs, chuckle. 🙂

LikeLike

No. Laughing. But I doubt they could match his slobbering/sliming capabilities. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Splendid tour, Alison! I’ve really, really enjoyed it. Like you said… just awareness.

I’ve to say, I sometimes wonder at the experience of those who came before us, like your Dad, when they travelled to faraway places they never knew they could visit. Sure, it was war and I bet that they’d much rather go somewhere else (and didn’t have time for wandering around), but still. I never had the chance to discuss it with my uncles, but those who took part in the invasion of Russia told my mother outlandish things, like tanks rolling over an iced-up river…

I feel a bit for the soft-shell turtle. Every turtle has a hard shell, they can sink back into it and good luck to the predator that wants to eat them… but ofor the soft-shell turtle. Doesn’t seem fair!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Fabrizio. It was a really special day; I’m glad you enjoyed it.

We all know of the atrocities of war and how many men suffered, but there must be a small percentage (and I think my dad may have been one of them) for whom it felt at least in part like an adventure despite the deprivations. I know he didn’t see combat, nor the inside of a POW camp, so that would have been a major factor. He could at least look around him and discover the nature of a tropical jungle, which would have been new for him. That much we know. I so wish now that I’d asked him more questions about it, but when he was alive I was far too self-absorbed.

Those soft-shelled turtles do okay. Those big claws they have are for digging themselves into the mud so they are completely covered except for their snout. I read that biologists have a hard time studying them because they are so hard to find.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

*◄থৣ💖

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

Alison

LikeLike

What an interesting place, Alison! I have added it to my Travel list. Hopefully, travelling is still possible when our world has had a chance to rest and recoup. I hope you and Don are keeping well and still getting out for some close to home walks. Luckily on Vancouver Island, we can socially distance on a variety of trails! Cheers and thanks for the wonderful report and pics of Borneo. Fascinating! Pat

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Pat. It was such a special day, I’m really glad we went. Definitely worth adding to your list though I would suggest an overnight stay there. The best time to see the wildlife is early morning.

We’re both well thanks, and out walking every day. We live near a golf course that is closed to golfers, but open to walkers (go figure) so we have a wonderful wide open green space to hike around in, plus we live near the Fraser River so we incorporate a trip down to the river in our walks. We have friends in Duncan so have explored quite a few of the trails in the Cowichan Valley – just beautiful. Some times we go to the endowment lands, or to the north shore to hike. We are so very lucky to be on the west coast.

Glad you enjoyed my Bako report.

Alison

LikeLike

Wow – what a great day! You cracked me up two times in quick succession with your comments about the proboscis monkey and the fiddler crab – I’m glad human males are not using scary noses or claws to attract us! As for the pig, I’m 100% with you on the (lack of) appeal; I was stunned to hear a few of my favorite readers honestly found that creature a little bit cute! Shudder. 🙂

The backstory about your dad was great, too. I find that a number of places that tug on me to see them have been planted there by something in my past. Our imaginations have such wonderful power, and for me it’s always been very fun to compare and contrast how a place stacks up against what I had constructed in my head. I’m so glad your Borneo experience lived up to the mystique it held for you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lexie. I’m so glad I cracked you up! That was my aim. I’m frequently amused by nature. I mean really – a big nose to attract mates?! Too funny. Apparently it helps increase the volume of their mating calls. But yeah, not so attractive. Soon I’ll post about a trip down the Kinabatangan River where we saw whole troups of proboscis so more pics of them to come.

There’s another of your fave readers who has just commented in favour of the pig (see below). Don and I both can’t find the beauty, or even cuteness in it lol. Poor piggy.

Borneo definitely lived up to the mystique. More posts to come on the above mentioned river trip, and orangutans! Such a special place.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison let me first say I am pleased Don had no serious injury form his fall. Like you I would have had visions of rescue helicopters coming to mind. So fascinating how that morning you decided to bring the first aid kit.

Your photos and description of Borneo are tantalizing. For some reason I am particularly fond of the ugly pig. I grew up on a farm which included pigs so perhaps I have a soft spot. Each animal has its purpose.

Hoping this finds you both well and that Don’s wound healed promptly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Sue. It was definitely scary when Don fell, and amazing that I had the first aid kit with me! His wound is completely healed now though there will be more to come on that story . . . . .

Borneo was quite special. I’m so glad we went, and that we stayed as long as we did even though we were racing the clock a bit with getting back to Canada before borders closed. It was Malaysia closing down that finally forced us to face reality.

Yes, each animal has it’s purpose, and I’m glad that pig has followers! (More than I would have guessed, chuckle).

We’re both well thanks. Hope you guys are too.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

The photo of your dad is incredible. What a connection to have with Borneo! Loved taking another look at Bako through your lens, with your thoughts. We have a wild pig short story (and photos) from an afternoon on a beach near Kuching. Maybe I’ll share it. Such an ugly creature, but important to the ecosystem — thanks for explaining that. 🙂 Happy weekend to you and Don. Great that he was okay after his fall. ~K.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Kelly. We have other photos of our dad, even as a baby, and teenager and young man, but this is the only one from the war, and it somehow made Borneo all the more exotic and special. As a child none of us up to and including grandparents had ever left Melbourne and a couple close by country towns, so dad going overseas was pretty special.

Do the wild pig post! Just for fun. Ugly yes, but important.

Don’s fully healed. We were lucky!

Have a good week to you two. Stay safe.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

That IS pretty special. What a memory! ♥ Okay, twist my arm! Ugly pig post coming sometime in the next week or two. Daily Dose of Ugly!? LOL. Happy to hear Don is all healed up. War wounds a good story! Gotta love travel. Thanks, Alison. You two stay safe as well. xo

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome adventure and great photographs. Sarawak is one part of Borneo I still have to explore, one day when we can travel again. In the meantime, it is great be able to read your posts and indulge in some virtual travel. For now, I enjoy sitting in an airy room with balcony not too far from the beach in Danang. At least I get some sea breeze. It could be worse.

Glad to hear Don’s fall was not too serious.

Lieve

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Lieve. I’m glad you enjoyed travelling to Bako with us! We’re all armchair traveling these days 😦

Your situation in Danang doesn’t sound too bad. I take it you’re not allowed on the beach?

Don’s healed, and we’re both fine.

Stay safe.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually the beach has now been reopened, but as a message from the Gods to encourage us to stick to social distancing just a little longer, the weather has turned and we have had a few rainy days… Still, life is getting back to near normal here with most shops and restaurants opening up. But there’s always the threat that lockdown could be imposed again at any stage. Uncertain times will be with us for a while.

Lieve

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the starburst pattern the crabs make on the beach. What a joy to see those all along your walk – along with the monkeys and turtles and fantastic sandstone cliffs. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen those starburst patterns before, on a beach in Oz I think it was, but never knew how they were formed. It was a great day – wildlife and wild scenery.

Alison

LikeLike

We loved Borneo and spent a day at Bako – our guide wore me out on the trails. It was only afterwards that he said the trick is to step on the tree roots rather than between them as you hike!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh good advice! We loved Borneo too. Wish we hadn’t had to cut it short.

Alison

LikeLike

Beautiful photography and I can only imagine…good to know Don was fine and you always create intrigue…all new to me…feels peaceful… hugs Hedy 🙋♀️🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Hedy. It was all new to me too, except the macaque. I’d seen macaques before, but not such a handsome one as this. It was a wonderful day.

Hugs back.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

It shows I love to share your posts with others who travel…as I said your narratives are authentic 🤓

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a sojourn you had – Borneo always sounds so incredibly exotic. No wonder you wanted to see it, with that family history. The rocks are fantastic – I love that kind of thing – and the snake, I can see how well camouflaged it is. The pig, wow! Great pictures of it!! I love the fiddler crab hideout with its starburst pattern, too, so cool. The turtle photo is also amazing – what a great experience that was! Thanks for taking us along, Alison. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lynn. My pleasure! It was a truly wonderful day. More about Borneo to come – an elly, and more proboscis, and orangutans, and sun bears. It’s an amazing place. I’m so glad we went even though people were saying we need to get home.

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It *was* fascinating! We’re so glad we went there.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a part of the world we have not yet visited. I do love visiting small fishing towns like Kuching with the colour boats and sometimes more colourful people! I liked the idea of taking a boat to the National Park. But not so much the idea that the guide needed to check for vipers on landing! I might never have left the boat. My only worry with the monkeys would be losing my sunglasses to them as I did in Bali. We wonder if we will ever get to such exotic spots again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We also love visiting the small fishing villages. I think you’d have been fine – it’s not like the vipers were waiting to jump out at you 🙂 they stay hidden in the trees. The monkeys at Bako were fine too, we didn’t see that many, but I know what you mean. We’ve been to many other places where you really had to be careful. Fun though!

I too wonder if we’ll ever travel again. We loved Malaysia.

Alison

LikeLike

Wow, I could feel the magic you felt! It’s in my own backyard but I’ve not been myself, not being drawn to the forest with its many dangers. I’m glad Don is all right.

The fermented rice is probably tapai, and I don’t like it either!

Did you know the sand ball patterns vary by place? I was on two different islands in Thailand and the crabs there have consistent patterns among themselves but different between the islands. One just dumped it wherever in a mess, and another neatly made concentric circles. Wonder whether there’s an equivalent crab ‘culture’. 😀

Thank you to your dad for enlisting for WW2. The pacifist soldier is the most worthy one for he doesn’t take the decision lightly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Nuraini. I gather you’re a water person so get why it would not be for you so much. I love forests and mainly don’t think of them as dangerous. We spent over a week exploring the Amazon jungle, similar in being a Malay tropical forest and loved it. Also I grew up in Australia and we have so many dangers there but I don’t even think of them. But here I am in Canada and worry about bears all the time we’re out hiking. It’s always something lol. On the other hand although I love being on the water I do think of the water, especially rough water as being dangerous.

I did not know about the crab patterns! I did see very similar patterns to these ones in northern Australia but didn’t know what made them.

I bet Darwin would have been very interested in the different crab patterns for different islands in Thailand. Reminds me very much of different tortoises for different islands in Galapagos.

I think dad had been mulling the idea of enlisting for a long time, and didn’t tell mum because he knew she’d be mad, but he made the right decision I think. I do wish he was still alive so I could ask him more about it.

Alison

LikeLike