20 October 2015. One afternoon in Luxor: we start walking from the hotel to the local food market. We’re hassled by a horse and buggy driver. As is the way of all hawkers in Egypt, he is very persistent, so we agree to pay five Egyptian pounds to get a ride to the market. He takes us to the old market of narrow crowded dirt lanes and starts to take us through there. People are complaining because the horse and buggy is taking up all the space between the stalls.

And anyway we want to walk. We want to experience the market and the people up close, not from the height of the buggy. We get out. We don’t pay him because we have some concern that we won’t be able to find our way back to the hotel, but mostly because he won’t go away. He wants to take us to the camel market, and says he’ll wait for us.

We walk around the crowded market. There are tiny stalls on either side of the alleyways, which are barely two metres wide. Clothing, fruit and vegetables, eggs, grains, meat, the place is organized mayhem, crowds pushing everywhere, vendors shouting, the smell of raw meat, of rotting vegetables, of fresh fruit, of tobacco smoke, of spices, of live chickens cramped into small cages.

It’s bedlam, but everyone is focused and has a purpose for being there. The movement is like a river as people flow about their business.

We wander, and look, and say hello. People are friendly. Some want their photo taken. Some are taking a break from the madness.

It’s quieter in the tributaries to the main stream. Here goods for sale are stored until needed, and here transportation baskets are stashed until the end of the day.

At some point in all this wandering and exploring we notice that our driver is shadowing us. He has apparently parked the horse and buggy down a side street and has been following our every move. Who can blame him? We haven’t paid him yet and he wants to take us to the camel market.

We come to the caged chickens. As I start to photograph them a man grabs one of the chickens, and an egg, and poses with it.

I immediately say no baksheesh (no tip) and take a couple of photos. He comes at me for payment. No one else has asked for payment, and some people have even requested photos, so I’m unprepared for this. He is persistent, but initially no worse than annoying. It is the aggressive child that starts to frighten me. The man persists, his tone becomes angry; the young boy becomes more and more aggressive. We don’t know what to do, but fortunately one of the many men who’ve been watching this little drama evolve pushes the man away from us, and we quickly leave.

On the first day of the tour Hoda, our fabulous guide, taught us la’ah, meaning no. I remember it by thinking of na’ah, which has the same meaning. She also taught us kalas meaning ‘go away’ to say very sternly to anyone hassling you more than you can stand. I remember kalas by thinking of alas. Alas I don’t want you around anymore, and alas you will not make a sale with me. Both have been useful words to know, and yet in the heat of the moment I don’t remember to use either.

We love local markets, and usually dive right in, but despite the friendly people this one feels stressful: there’s a tension highlighted by the chicken man and the aggressive boy and the on and off haggling with the horse and buggy driver. At one point we send him away and say we’ll meet him when we are ready. We have not yet renegotiated the price.

We rejoin our driver and climb into the buggy. Now he says he wants to take us to a bazaar because they will give him food and water for his horse if he takes us there. We believe him.

We are in and out of the “bazaar” in five minutes – it is filled with what we call “tourist tat” and nothing at all that we are remotely interested in buying. He says he was not given water for his horse because we didn’t buy anything. We believe him.

We set off to the camel market “which is only open on Tuesdays”. Of course it happens to be a Tuesday. We believe him.

We drive through the busy madness of Luxor where the traffic is relentless, and the market has spilled out onto the streets.

We drive past security guards smoking sheesha

and down crowded narrow alleys.

I will take you to the camel market, he says,

and we are aware that he could be taking us anywhere. As we trot along he tells us of his four children, and his poor horse Sophie, and how there’s been no business for five years since the tourists stopped coming. He’s pathetic and whiny and desperate and angry. Every horse that goes by he points out how skinny it is. He tells us that two hundred horses die every year. We believe him. He tells us that he has to pay for food for his horse. We believe him. He tells us that he has to pay for water for his horse. We are in a town situated on the banks of the biggest river in the world, and yet we believe him. He says again that he has four children. When I ask how old he says ten, and then hesitates, then says four, three, two, and one. Perhaps something is lost in translation. I want to believe him but I’m starting to have my doubts.

The “camel market” is a very sad courtyard containing three very sad horses, one of which stands in the blazing sun, and a donkey eating alfalfa. He tells us we’re too late; the camel market is finished for the day. We believe him, even though two days earlier another man had offered to take us to the camel market, saying, on a Sunday, that it is only open on Sunday.

By the time we get to our hotel we’d already agreed to pay fifty Egyptian pounds, but he pleads for more so we end up paying seventy.

Whatever lies he told us, there are very few tourists in Egypt these days, business is not good, and people really are struggling. We were taken for a ride in every way possible. We always start out suspicious, and haggle hard, and then grow tired of the game. We are suckers every time for a hard luck story. Every time. And he was very good at his job. Whatever the lies, whatever the circumstances, we are are better off than they are and it feels so mean and so cheap to keep arguing about the price. In the end we paid him the equivalent of Canadian $12 to be driven to the market, and then all around town on a wild goose chase. We did get to see more of Luxor, and I got to rest my poor aching hips.

And this is what we learn from Hoda: No horses are dying. If they can’t afford to keep the horse they sell it. And for the past year the government has been paying horse and buggy owners a pension of 700 pounds per month for the care of their horses.

There is no camel market in Luxor.

And oh good lord I’m embarrassed to admit we believed he had to pay for water for the horse! Really! What was I thinking? Or more accurately not thinking. As I said, we’re next to the biggest river in the world, and in Edfu I’d seen horses being washed in the river so I knew they took their horses down there, and yet I believed he had to pay for water for his horse. Face palm! Everyone has to pay their taxes. Apparently it was time for us to pay Stoopid Tax!

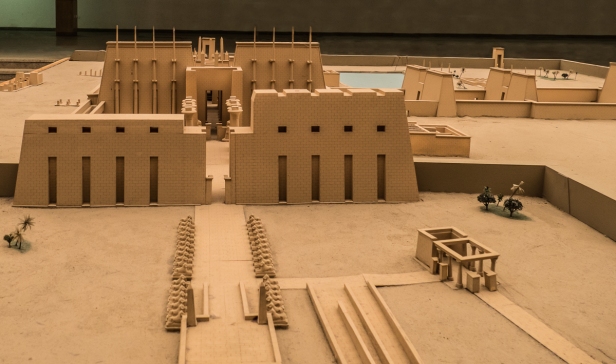

That afternoon, safely back together with Hoda, we go to the extraordinary Great Temple at Karnak. It’s another of those places of the ancient world that I learned about in high school. It is the largest religious building ever constructed. It is a city of temples built over two thousand years and covering two hundred acres, and for the largely uneducated population it must have been truly awe-inspiring.

It’s hard to conceive of the power of Karnak. It was the religious and political centre of the world for the ancient Egyptians, it was the place where the pharaoh was linked in ceremony to the god Amun, where the pharaoh was deemed and seen to be also a god, where ordinary people came in devotion and supplication and obeisance, and where religious rituals and ceremonies were carried out on a grand scale. Karnak was the centre of the universe.

This is what we see today.

The entrance to the hypostyle hall

The scale is breathtaking. The hall covers an area of 50,000 square feet and is filled with 134 enormous columns eighty feet tall. In ancient times, the columns, and indeed the entire temple complex was painted in brilliant colours.

The sacred lake was used for ritual washing, and was home for the sacred geese of Amun. It was surrounded by storerooms and living quarters for the priests.

One can only imagine the power plays and politics that went on over the years within the walls of this vast religious complex. And get this: during the big religious festivals sometimes some of the ordinary people were allowed into the depths of the temple to question the gods. The replies came from priests hidden inside statues.

From Luxor we fly back to Cairo, coming full circle on our journey through Egypt.

Next post: the exhilarating insanity that is Cairo.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2016.

I would tend to rack it up to the heat – believe me!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, great idea! And it *was* hot, really hot.

Alison

LikeLike

Amazing! 😀

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. Everywhere we went in Egypt was amazing.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please do plan your next trip to the Rannotsav this Dec-Jan. It is held in India, Gujarat in the White Desert. There is nothing like it and the weather is lovely! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just had a look online about Rannutsav. It looks amazing. We won’t come this year as were already committed to Yucatan, Cuba and Central America during that time, but I’ll put it on the list for the future.

Alison

LikeLiked by 2 people

Ohhh….that’s so cool…I look forward to your planned trip. And whenever you plan for Rannutsav, let me know. I’ll do whatever I can 😀 Happy Travelling guys!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your photos through the market and streets were amazing and the perfect backdrop for your story. It is frustrating to be taken advantage of, and very easy to do when we want to believe. however as you say, at the end of the day for $12 CAD you got to see a lot more of Luxor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much. In the end we didn’t mind. It was only $12 for us but was probably a huge, and much needed bonus for him. I wish him well. He was really good at what he did, and we were just suckers for a hard luck story 🙂

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

As usual, some splendid pictures and a wonderful journey!

I especially love the picture of the old lady selling a basket full of grain (?). Her face, a sign of all the hardships she has undergone, her expression, one of pure desperation! Beautifully captured!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Aishwarya. I was thrilled with that photo of the old lady. Usually in a market I’m just snapping, so it’s lovely when I manage to capture a moment like that. Yes the hardship shows in her face, but I don’t think she was desperate in that moment – she was talking to someone, a customer perhaps. But yeah, she’s had a hard life.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful photos. Especially love the night shot and the carriage.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Peggy. Isn’t that carriage something! Though I do think it has seen better days. And the temple lit up at night was beautiful.

Alison

LikeLike

I’d say you did well for $12 – especially if you got back in one piece with all your stuff! You got a great set of photos out of it also. I love the photo of Luxor temple at night – the first photo. Was the figure posing for you or just a coincidence?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Helen. I think we did well for $12 too, especially considering what happened to you! The figure at the temple was just there.He’s probably a guard.

Alison

LikeLike

OMG, this is exactly what would happen to us, I am sure. You did get some good pictures, though. The fact there is no camel market is quite funny when you think of it. You were returned to your hotel unharmed so all was well.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Darlene. Yes I definitely got some shots I wouldn’t have if he hadn’t driven us all over town so there is that. We were such a pair of doofuses, but I hate the feeling of being cheap, and clearly he needed the money more than we did. The touts of Luxor must have figured that western tourists a) would be interested in seeing a camel market, and b) have no idea that there isn’t one in Luxor. I guess we felt safe enough because it was broad daylight, and there were always plenty of other people around.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant read and superb pictures, as always x

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Joanne, glad you enjoyed it. It was quite a journey!

Alison

LikeLike

We heard the same stories with our carriage driver a few years ago. There are also some charities that were helping oversee the horses in conjunction with the government. I think the donkeys suffer more!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems the touts have figured out which stories work the best and then use them over and over. And yes, there were some very sad looking donkeys. I suppose they’re lower on the totem pole.

Alison

LikeLike

I also had a similar experience when I chose to believe what some people said even though they sounded like those you can’t trust. On a side note, I always love your photos of the ancient Egyptian temples, Alison. The massive hieroglyph-covered pillars of the Great Temple at Karnak always take my imagination back to thousands of years ago when it was still used. Just magnificent!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Bama. Karnak is magnificent! and must have been even more so when the colours were fresh. Did you click on the links to the temple and to the hypostyle hall? They give beautiful illustrations of what they would have looked like. The link to the page about the hypostyle hall contains a short video showing the hall in full colour as if you are walking through it. It’s absolutely breathtaking.

I think anyone who travels a lot must get sucked into a sob story and believe the lies from time to time. I don’t begrudge him the 70 pounds, I’m more annoyed at the time wasted being taken to the awful tourist bazaar than anything else.

Alison

LikeLike

Yes, I did. Watching how ancient grand monuments would have looked like always gives me goosebumps. It makes me think of the ingenuity and creativity of the architect who lived thousands of years ago, at the same time it makes me feel rather insignificant.

Exactly what I feel. It’s not about the money, but it’s more about having to do something against your own will.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh I so wish to go to Egypt! I studied it at university and came so close when I worked aboard a cruise ship but the port stop got cancelled due to ‘political unrest’. I thoroughly enjoyed your pictures though. I’m also one who finds it hard to say no when I’m travelling, but like you said, when you visit some countries what is not a lot for you can be a very welcome bonus for them!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Emily. Go forth to Egypt! It’s absolutely amazing, and I hope you get there one day. I hope that carriage driver made really good use of his 70 pounds. It was an experience for us, and we got to see Luxor in a way we wouldn’t have otherwise.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice job on capturing the bustle of the markets. It’s amazing the variety of stuff spread willy-nilly in a place like that, and having just seen something similar in another part of the world I can still remember the smells and chaos. As for the “tourist tax”, I can relate there too. Sometimes it seems worth it to haggle just for the experience and for principle, sometimes it’s “these folks aren’t very well off, why am I haggling for a dollar or two?”

Karnak is one of those places, like the pyramids that seem like a wonder of the world. Can you imagine the place roofed in with a paint job?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Dave. I love local markets, you always get a taste of real life there. I do so get tired of the haggling, especially when it translates to a small amount for me. You must click on the links for Karnak – you will get a visual of what you’d be imagining. On the link to the hypostyle hall there’s a short video taking you through the hall as it would have been. It’s breathtaking.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

First of all, Karnak is truly awe-inspiring and I have to compliment your magnificent photos of it! But I always love the small stories, the here-and-now people stories, so I loved being taken on that ride, even as it raised my hackles, worried me for your safety, and then deposited you back where you belonged, poorer only by a bit of cash. I am sometimes ashamed of my suspicious nature when things turn out perfectly fine, and just as often ashamed of my gullibility when I get taken! It was a great story and, as you said, you are far the richer for the incredible photos and experiences you found in that (crazy!) market and city. I felt overwhelmed just looking at some of the scenes on my screen!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Lex. I agree, Karnak is awe-inspiring. You should click on the links to see it restored and in full colour – I can hardly imagine what it must have been like to be a part of the religious festivals back then. It is so gorgeous, and the priests speaking as god while hidden in statues! People must have been totally enthralled. As for the horse and carriage ride – what an adventure that was. The market was crazy, and a little scary, and then him taking us all over town – we were a bit worried for our safety too, but not overly so. I too feel a bit ashamed when I’m wrongfully suspicious but I don’t think it’s misplaced when you’re travelling.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your writing and photographs make it all so very real for me and you express your thoughts beautifully. Thank you for taking your time and energy to share with us. My wife and I experience many of the same feelings about “bargaining” and I just said to someone today in Kosovo that we paid 4 euros for a cab ride today that 2 years ago we would have bargained down to 3. Will be in Cairo and Luxor next month. Can’t wait.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Steve. I often start out bargaining, but get tired of it very quickly, and with people as persistent as the Egyptians I probably paid more than I should have more than once. Be aware for when you visit – they are very pushy. Remember that word kalas. And say it with force. Apart from that Egypt is amazing. Have a great time there!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Travel has its challenges to be sure. i so enjoyed your photos of the market and could almost hear the bustle. Glad you made it back in one piece and with a great story to tell.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Sue. That market was crazy, intense, vibrant. Everyone seemed to know exactly what they were doing, and we were the only foreigners there. I’m glad we went with that man, even if we were a bit anxious from time to time. It’s the way to get the best experiences.

Alison

LikeLike

You are brave. I would be the same about paying too much as the poverty is heartbreaking. Your pictures are stunning!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks so much Debbie. I suppose we were brave, but we always just plunge in expecting people to be good. Knock on wood, it’s worked so far. We’re not too reckless – we would never have done the same thing at night for instance. Everywhere we went in Egypt we could see the effects of the downturn in tourism, so in the end I didn’t mind paying the 70 pounds. I hope he spent it well.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would have hated every second of the opening sequence, Alison. I guess it’s why so many people only go on guided tours. Karnak looks formidable but life on the streets isn’t for me.

LikeLike

Karnak was amazing, and even more so in its original colours. I’m so glad I got to finally see it. As for street life, it’s one of our favourite things to see so we just plunge in.

Alison

LikeLike

I’ve just come to the end of your previous post, Alison, and was about to look at the tombs in colour before commenting. I’m very struck by your emotional response to them. Communing with a long gone world. 🙂 The quantity of hieroglyphics is extraordinary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a very powerful experience for me in the tombs – a sense that I knew what it was all about but couldn’t remember, or translate. That night back in our hotel room I cried and cried – it was a grieving for something I felt I’d lost long ago. Very powerful.

Alison

LikeLike

Amazing to connect like that!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes it was. Did you click on the links to see Karnak in colour? It is glorious. In the link to the hypostyle hall there’s a very short video that shows what it would have looked like walking through it back when it was new.

Alison

LikeLike

Just the first link. I’ll go back if I have time. Awe inspiring to see.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant photographs. Particularly cherish the night shot and the carriage…Brilliant read and magnificent pictures, as usual

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. I’m glad you enjoyed it. I’m sorry I’ve taken so long to reply. I found your comment in the spam file!

Alison

LikeLike

wonderful learnings…I always struggle as an outsider and not having the language…I live the images and history…I can feel the adventure as you’ve written here Alison…you are real adventurers that I know 🤓☺️

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Hedy. We too struggle with not having the language, so rely on universal body language, and smiles, which I’m sure you do too. Sometimes it’s a bit scary, but mostly it’s exciting and people are friendly and generous. I suppose we are adventurous. It’s mostly that we just want to know, and I am endlessly captivated by the exotic so I just plunge in.

Alison

LikeLike

Such a great post and beautiful photos. That temple of Karnak looks amazing – it also looks like it’s from an old James Bond movie…there’s one movie which starts in a place like that. Do you ever get tired of traveling to places where the cultural difference is so huge and you’re treated like a walking dollar sign? Your descriptions sounds kind of exhausting to me, as amazing an experience as it must’ve been. I’m sure it was worth the trip for the temple and other ruins, but I did seem to note a neutral tone in your writing, instead of pure joy. Or am I imagining?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks TSMS. Karnak is a truly astonishing place. It must have been absolutely breathtaking when it was all painted in bright colours.

I love going to exotic places where the culture is different – I’m really excited by it, even after all these years, but there is a rhythm to travelling for us. We’re good for a few weeks, maybe two or three months of continuous travelling, and then we stoop in one place for a while. The past year has been very slow travel for us, a few months in just two places in Mexico and now nearing the end of five months in Vancouver.

You’re not imagining the tone in my writing however. It’s more a reflection of my head space when I was writing this post (almost a year after it happened) than a weariness with travel. Sometimes I get caught up in wanting to get it done, rather than letting the inspiration come. I caught this mindset after the fact, so hope the next post will be a little more inspired. I was certainly not feeling neutral about any of our time in Egypt – it was a travel highlight for me in so many ways even if we did get taken for a ride in Luxor.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I did (and do) love your writing, I hope you know that! 🙂 I guess I was reflecting my own travel attitudes, when reading, too. I find it tiresome to travel as an obvious foreigner and love it when I blend in. As a tall-ish blonde, that doesn’t always happen.

LikeLike

Thanks 🙂 I do know that. I’m also aware when I’m struggling a bit with it. And I do sometimes wish I could blend in a little more.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like a day that nagged at you throughout– that tugging discomfort of uncertainty about what is transpiring between oneself and another human being with whom one is however briefly entangled. I find it an uncomfortable place to be when I’m in it. I often punt and try not to worry about being taken advantage of. If I was at home $12 would hardly get me ten blocks… It’s funny how our perceptions shift depending on who is doing the talking!

Karnak looks amazing. I love how the pool of water that once would have perhaps rippled with sensations of potency and power now, in the photo anyway, seems such a simple thing. We humans bring so much to the moment with our ways of seeing…

Peace

Michael

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes it was a (half) day that nagged. We never got to feel quite relaxed, he was so persistent, though we were never seriously stressed either. Just, as you say, nagged at, and it was our own fault. We never really got a handle on the situation. But in the end it was only $12 which is nothing in the big picture, nothing even in the small. Karnak is truly amazing – those columns in the hypostyle hall are enormous. I’d love to have seen it all new and coloured with shining marble floors. The pool is beautiful in the way all water is when reflecting the soft light of the setting sun. I think in ancient times that pool would have been something quite glorious. I seemed to see all of Egypt through grieving eyes as if I was returning after eons to something I’d lost.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing story and accompanying photos Alison! So now you’ve got me very curious. You are writing all these stories in so much detail from the past. I feel like I can barely remember my trips like this. Do you take documented notes or a travel journal each day? I used to write a documented journal but now I’ve found my travels are so crazy and busy that I just take notes. But I’m wondering if I should go back to my journal and document each day. Your stories are amazing and impressive!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Also, we all can easily fall into these traps. We want to believe in someone yet often I think we can easily get taken advantage of as well. It is always a learning experience!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Nicole. We were total suckers for the horse and carriage driver. But kind of dependent in a way too. We did want to see the camel market, if there had been such a thing! And also we hadn’t been paying enough attention as to how to get back to our hotel so we thought we needed him for that.

Our whole trip through Turkey, Jordan, and Egypt I made notes every night – sometimes brief notes of what we did that day, sometimes more detailed descriptions. This story of being taken for a ride in Luxor for instance I wrote in some detail because I wanted to be able to do a blog post about it. Also I remember a lot through looking at photos. There’s so much detail in photos that I discover as I’m going though them.

After Egypt we had two months in Vancouver, three in San Miguel de Allende, two in La Manzanilla, and five in Vancouver – I’ve hardly made any notes at all, though I feel there’s not that much to tell since it was more like just living in a place than travelling. So it really varies, and definitely affects what goes in the blog.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just loved this story. Sometimes we are stuck in ways when traveling and do our best with what options are there. If you didn’t take the driver then you wouldn’t have had this story! I’m going to try to take better notes myself as the older I get the harder it is to remember in detail the stories! You sure have done a lot of traveling Alison! Where to next?

LikeLiked by 1 person

We don’t regret taking that ride in Luxor – there were a lot of positives in it. Nov thru Feb we’ll be travelling around the Yucatan Peninsula, Cuba, and parts of Central America, then May thru Sept we’re off to Spain, Portugal, and Morocco. We don’t stay still for long 🙂

A.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh Alison sounds amazing!!!! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am always glad that you have such a fascination with local markets. I like them in theory, but having been to a few in the Caribbean, I now know that my comfort level when people are hustling, hawking, pushing, and haggling is non-existent. I like the feel of a laid-back, American farmer’s market, but I don’t think I’d enjoy going into a market like the one in Luxor.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We love the local markets, though it’s true some are more manic than others. This one was particularly manic, but so worth it, and now you don’t have to go because you’ve seen my pictures 🙂 There was no pushing and haggling in the Luxor market except for our buggy driver and the chicken man. Everyone else left us alone, and were generally friendly. I think it’s very important to distinguish between the markets where the locals shop – these markets you will generally be left alone to just look and enjoy the atmosphere. Tourist markets on the other hand are different and you’ll likely he hassled a bit, or a lot, depending on what country you’re in. We’re always looking for the local markets, especially since we seldom buy souvenirs.

Alison

LikeLike

Since it was both fascinating and overwhelming to read this post, I can only imagine what it was like to *live* it. Wow.

Your experience with the driver is poignant. In this jaded age, it’s actually a kind of gift to still be trusting and gullible. You did a good turn this day, pilgrim. ❤

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Jen. It was definitely fascinating, and at times a little overwhelming. Mostly we just went along fro the ride 🙂

I did feel for the driver. I think he’s a good man, just doing what he needs to survive. And his way of doing it is part of the Egyptian culture, so it’s what he’s learned, what he knows best. I do so hope he enjoyed his windfall.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

ah yes the stoopid tax, we all have to pay at some point! I enjoyed this post so much the first time round, and thank you for reminding me of it! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Danila.

LikeLike