4-5 October 2015. According to Rough Guides: “Jordan’s public transport is a hotchpotch. Bus routes cover what’s necessary for the locals, and there is little or no provision for independent travellers.” There was a train from Amman to Damascus in Syria, but Syria is sadly not a good destination choice these days, and the last time the train ran was in 2006. There is little else available. Again from Rough Guides: “Locals know the system by word-of-mouth, but no official information about bus travel exists: in most situations, you simply have to turn up at the point of departure (which may not be advertised as such) and ask around.” We decide to take a tour.

Apart from the Galapagos Islands, where it is mandatory, it is our first tour, though I’d done a couple of extended overland expeditions when I was travelling in my twenties. Our group consists of eighteen people: mostly Brits, with a couple of Americans and us Canadians. There is a great luxury in taking a tour. Suddenly, and gratefully, all responsibility is handed over. We no longer have to think about where to go next, or how to get there, or where we’ll stay. We even have people to carry our bags. There is a great relaxation.

So it is day one of our weeklong tour through Jordan. We all pile into a big bus, and from Amman head north to the ancient Roman city of Jerash, a city that, until recently, had been covered in sand for centuries.

The site has been inhabited for over 6,500 years thanks to its proximity to fertile hillsides and a wide, deep wadi that is cultivated to this day. In 63 BC Jerash became part of the Roman Empire and the city’s golden age began. Known then as Gerasa, it is one of the world’s best-preserved Roman provincial towns. It is classic urban Rome of the Middle East. We enter through Hadrian’s gate

to find paved and colonnaded streets,

a grand public plaza,

and lofty hilltop temples.

There were once baths and fountains, a complex drainage system, and a main street lined with shops, public buildings, and the homes of the wealthy. The ruts in the paving from countless chariots help bring the scene to life, but in a place so long forsaken that it was buried for centuries our only company today is lizards.

Modern Jerash lies on the eastern side of the wadi. As in the days of Rome the population lives on this side. Ancient residential Jerash lies beneath. The western side was largely devoted to administrative, religious and commercial activities. In those days causeways across the wadi connected the two sides.

Of course, in the fashion of all Roman towns, there is a theatre, with acoustics so good that an annual music festival is held there. What is completely unexpected, in Roman ruins in the Middle East, is the sound of bagpipes. As we enter the theatre we see them: a drummer and a piper. They are wearing traditional Arab-style robes, or thawbs, and one is wearing a Jordanian headscarf, the tasseled red-and-white shemagh. The setting and their outfits are a surprising juxtaposition to a drum and the traditional instrument of Scotland. Afterwards I realize that since Jordan was once a British protectorate, the music would have come from that influence, and I discover that their robes, in that desert brown colour, are standard Jordanian military dress uniforms, though I doubt either of them is actually in the military.

A few million years ago the Arabian tectonic plate and the African tectonic plate started slowly moving apart forming a long north-south depression. It created the path of the legendary Jordan River, which today forms the border between Jordan and Israel. At its widest point the river became an ancient lake. The lake extended from the Sea of Galilee in the north to the Dead Sea in the south, a distance of some two hundred kilometres. Eighteen thousand years ago the outlet from the Dead Sea into the Sea of Galilee dried up, forming two separate lakes. The Dead Sea was left behind in a desert basin at the lowest point on earth, some 400 metres (1300ft) below sea level. Because there is no way for the salt to leave the basin, salt and mineral levels increased as the water evaporated. Eventually the water reached the highest concentration of salt of any body of water in the world.

Slowly we all make our way into the water.

Many are wearing sandals or reef shoes – it’s a bit crunchy and rough underfoot.

When I’m in far enough, when the warm water is deep enough I slowly sit down and lift my feet. Without effort I’m floating, bobbing like a cork on the ocean.

Floating in the Dead Sea is a unique experience. It is not our first time floating in extremely salty water. That came in Lago Cejar in the far north of Chile. The two are hardly comparable in size. Lago Cejar is lake sized. The Dead Sea is also a lake, but it is the size of a small sea. It is 67 kilometres (42 m) long and 15 kilometres (9 m) wide at its widest point.

And it has waves. Not big waves, but they are still waves. I mention the waves because it’s really not a good thing to get any of this hyper-salty water in your mouth, or eyes, or ears, or nose. So instead of just floating I find I am battling to stay upright. I have to constantly fight against flipping over. Not everyone, it seems has this problem.

The Dead Sea was one of the world’s first health resorts. The waters have been famous for their healing powers since ancient times. These days, even if you’re not at one of the high-end resorts to be found along the shores on both the Israeli and Jordanian sides, you can still cover yourself in the healing mud from the water. The mud is the alluvial silt washed down from the surrounding mountains and deposited in the water along the shores. Layers and layers deposited over millennia have resulted in a rich mud containing high levels of minerals. It is said to be very good for the skin, and several cosmetics companies market Dead Sea mud for facials. Don and I decline the mud, but others in our group dive in for the full experience.

On returning to Amman we don’t go out with the group for dinner because we want to go back to our favourite hookah bar near the hotel. We eat a huge Greek salad, a pile of hot pita bread, and a big bowl of hummus, finishing off with divine chocolate and vanilla custard. It’s one of the best meals, among many, that we have in Jordan.

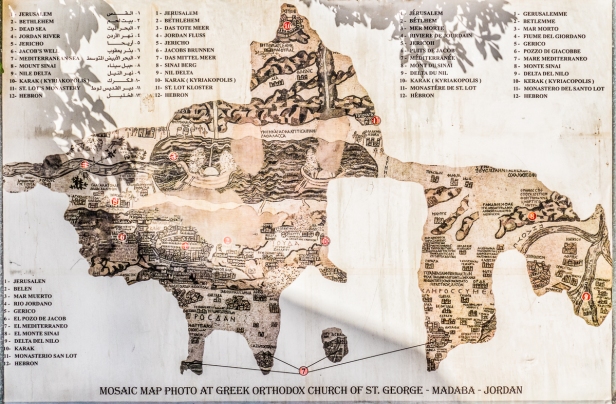

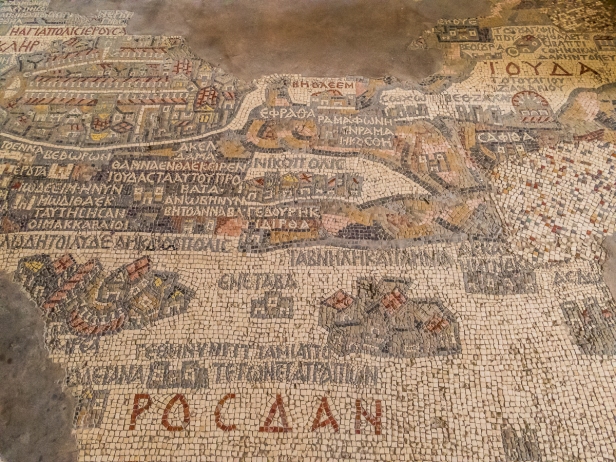

The remains of the oldest known map of the Holy Land, created in the 6th century by an unknown artist, lie on the floor of the small Byzantine church of Saint George in the town of Madaba.

Crafted meticulously from coloured glass and stones, the map depicts the Holy Land in great detail. Much of it has been lost over the centuries with only about one third of it remaining.

Although it runs north-south the map shows the Jordan River in an east-west orientation surrounded by all the important landmarks of the time including biblical locations. Places and events are labeled with 150 inscriptions in Greek. Jacob’s Well, the Oak of Abraham at Hebron, Jericho ringed with palm trees, and John’s baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River, are all depicted in detail. There are fish swimming in the river, one of which is turned away from the toxic Dead Sea. There are two boats on the Dead Sea, and ferries across the river. There is the Nile River Delta, Mount Sinai, and Bethlehem. Jerusalem is depicted with most detail of all: a sumptuous overhead view of the walls and gates, the main streets and over thirty major buildings, many of which are clearly recognizable. It’s an extraordinary work of art and an enormously important historical record.

Sadly I didn’t recognize the wonder of it when I was there. Perhaps I’ve seen too many ancient mosaics and was suffering from ancient mosaic burn out. It is only through my research for this post that I have come to understand what I saw: one of the earliest maps ever created, before the advent of any kind of cartography. I think it would be a wonderful thing if there could be a brochure at the church for visitors. The brochure could have a picture of the map, like the one above that is outside the church, and several pictures of detailed parts of the map, each with a brief written description, and a translation of the Greek. This would make it easier to decipher. I love details, but I really had no idea what I was looking at, and of course the Greek lettering was all Greek to me. If I’d had such a brochure I probably would have spent a long time looking for all the different illustrations contained in the map. I’m sure I would have been drawn in – where are those palm trees?, oh look, there are the fish in the river, and look there are even pulleys across the river for the ferry boats, and there’s John baptizing Jesus. It’s a map and an illustration of the events of the Holy Land, and I’ve been pouring over photographs of it trying to identify some of the details.

The second day of the tour is a long day that takes us from Madaba to Nebo to the fabulous Kerak Castle built by an ex-butler during the Crusades, and finally to Petra, the ultimate highlight of any visit to Jordan.

Next post: Scenes from the bus, Queen Rania, Syrian refugees, and the great Crusader castle at Kerak.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2016.

That sunset photo at the beginning is divine, and Gerasa looks amazing. What a refreshing dip in the sea! Can’t wait to read more. Thanks for this escape on a quiet Sunday afternoon. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Kelly. The sunset photo had a little help from Photoshop. I am not a purist 🙂

All three places were worth visiting, but I guess pale in comparison to Petra. Well pretty much everything pales in comparison to Petra.

Alison

LikeLike

this looks incredible! I’m a travel blogger on here too, love your blog! 🙂 http://www.tifness.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Latifa. It was all pretty amazing. Your blog looks great.

Alison

LikeLike

Hi Alison,

In some ways I think no trip is complete without at least one shoulda, woulda, coulda. Or one photograph I forgot to take. It reminds me that there is only so much energy you have and it is impossible to see, do, and appreciate it all.

As a traveler and sailor I love the mosaic map. It sounds like you may even appreciate it more now, in having done all of your research, then you might have if you had known. Who knows? There in lies the wonder.

Cheers,

David

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well yes, there’s always a woulda coulda shoulda isn’t there. There is a constant reminder that we can’t get to everything, or that even what we get to may not be as fabulous as we’d hoped. I do appreciate the map way more now and wish I could see it again – with an expert to show me all the details and translate the Greek! And yes, you may well be right – that I appreciate it all the more for having learned about it after the fact.

Alison

LikeLike

Fabulous pics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Peggy, glad you enjoyed them. Jordan’s a pretty amazing place.

Alison

LikeLike

Fantastic! What a twist on the tour experience. Cannot wait for your take on Petra. Thanks for being a part of my Sunday afternoon escape, as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Robyn, glad you enjoyed this little afternoon tour 🙂

It was overall a good tour and we’re glad we did it – we didn’t necessarily get to see *all* the best of Jordan, but we definitely got to see the highlights hassle-free. Petra coming up.

Alison

LikeLike

Thanks again! Super.Just so you kow, I read all your posts… top to bottom. K

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Keith! I’m glad to hear that you’re enjoying the blog. Were back in Van end of May for 5 months – let’s get together.

Alison

LikeLike

To walk these ancient colonnaded streets, to walk through Hadrian’s gate, to swim in the dead sea (or bob around like a cork), blows my mind. Things I remember reading about in school. What a glorious thing to have done this. Great post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Angeline. Yes it is amazing, though I knew none of this when I was in school except for some vague notion about the Dead Sea. But to be in it! Incredible!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

So many stunning sights and experiences. Jerash is breathtaking. And that map!

So many treasures and a great salad to finish!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jerash was really amazing to wander around. There’s a lot to see there, and there is heaps still to be uncovered. The Dead Sea was a totally unique experience – nearly as good as dinner that night 🙂

I’m so glad I did some research about the map. It gave me a whole different appreciation of it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fabulous trip, Alison and Don. So much to see and do there. The photos are amazing and I love the full commentary – very informative and makes me want to visit there too, I have visited the Dead Sea on the Israeli side. The whole place is just so amazing. I look forward to the next episode. Bless you both and safe travels.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Isabella Rose. Yes, it was all pretty amazing. We loved it. Go visit! It’s definitely worth it 🙂

I’d love to see the Israeli side. I’d love to go to Jerusalem. Maybe one day. A girl can dream.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jerusalem is wonderful, but it was the Sea of Galilee for me. I’d dreamed of being there for a long time and suddenly I’m living the dream. Fantastic. I’m going back one day. Well recommended.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous photos and story.. Huge thanks as always for sharing your experiences.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ros. I’m glad you’re enjoying the blog. Are those pesky wombats still digging up your garden?

Alison

LikeLike

What a great adventure. Eli was in Jordan last year–just kind of showed up and caught a ride out to Petra in the back of a jeep. (I’m glad I didn’t hear the details until after he was safely back in Turkey). I look forward to learning about your experience there.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It was pretty amazing. We enjoyed Jordan, especially Petra which is extraordinary. I love the way Eli travelled. I wish I was still that adventurous but we’ve become too attached to our creature comforts.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad I didn’t know about it until after he was out of there!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous pictures Alison especially all covered in mud and bathing in the sea. I would LOVE to go to Jordan. It has been on my wish list for ages.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Nicole. The Dead Sea sure was a great experience. I don’t know why Don and I declined the mud – feeling lazy I guess. We washed the salt off and went for a swim in the pool instead. It was lovely. I hope you get to Jordan. It’s definitely worth it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an experience. I am so happy that you took the photos of the ancient mosaic map – what a thrill it must have been during your research to realize how special they were. I am learning that photos help us enjoy our travels over and over. All the bet to you – Susan

LikeLiked by 2 people

It was a fabulous experience – all of it, even if I didn’t get the mosaic until afterwards. Now I wish I’d taken even more photos. I probably would have except there were lots of people around so it was hard to get to all of it, but the ones I have are plenty good enough to remind me of what I saw.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow this is such a great experience. The pictures are beautiful and walking through so much of history and ancient beauty must have transported you to another time.

I loved reading it. I wish I can visit these places some day.

The description is very interesting and informative.

Thank you for the post. It was a pleasure reading it. Look forward to reading more.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Maddy. I’m glad you enjoyed this journey to Jordan. It’s a remarkable place, rich with history and I’m so happy we got to see a little of it. Next post will be a bit about modern Jordan. I hope you get to visit one day. It’s definitely worth it. Much more to come 🙂

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great. Can’t wait to read them

LikeLike

My mum once lived near the dead sea, as kids we thought she was having us on about being able to float in it. We thought she was kidding about going camel racing too, turns out it was all true 😊

The mosaic map is remarkable, and you’re right, a wee leaflet or something to give visitors some clue as to what they’re looking at would be a grand idea. Still, how lucky you are too have seen it xx

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Tina, thanks for commenting. I love the title of your blog. I agree we’re very lucky to have seen the mosaic, I realize that now, *and* a leaflet would have been nice. Still, it made me do all this research and now I know more about it than I ever thought I would. The Dead Sea experience was remarkable. I’ve only ever seen a camel race in India – it was completely wild. I would imagine those in the Arabic countries would be well organized and somewhat serious affairs. I’d love to see one.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I can’t take the credit for its name though, it was down to my youngest. I was pondering on what to call it when she drew the picture. “Its a sock” she said “I know I’ll draw it a bath” well why wouldn’t you?

I’m not sure if the camel racing still goes on, mum lived in Aden when she was a teen, she’s now in her sixties. We have some black and white photos of the racing, as kids we’d stare at them for hours fascinated. My grandad was in the RAF and they were stationed out there, they lived in a block of flats with nets on the windows because folk would throw hand grenades in. Very different to my teenage years.

I loved reading your blog and seeing your photos, thanks for writing xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

I figured it must have been one of the kids. It’s a great name. Your mum sure had an incredible childhood!

A.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She did but her life became so much more exciting when I came along 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chuckle 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know you were not crazy about the monochromatic look of modern Amman, but did you love the old monochromatic stone of Jerash? I LOVE the look of it! So soft and warm looking. I enjoyed my float in the Dead Sea last summer but, like you Alison, I kept almost tipping over and getting a mouthful of salt water! Another blogger introduced me to the mosaic map and I was fascinated. I wish we had made it north to Amman and environs when we were in Jordan; I would have loved to see that in person.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I was fascinated with Amman, loved it actually, but you’re right, not crazy about the monochromatic look – I’m always drawn to colour. It’s the reason I doubt I’ll ever get into B&W photography though I experiment with it now and then. And yes, even so, I do love the look of Jerash. Somehow for me monochrome works for ancient sites in a way that doesn’t for a modern city. Yay – glad to hear someone else had a struggle with the Dead Sea. I’d have loved to luxuriate in that lovely warm water, but didn’t feel like I could ever really relax. I’m fascinated with the map now, after the fact. Maybe one day I’ll return, but probably not. If I was going back to that part of the world Jerusalem would be at the top of the list.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a bummer that you didn’t get to Jerusalem when you were in Jordan; I remember you wanted to go but it didn’t work out. Next time! (My mantra – haha)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow this is beautiful pictures

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Akansha.

Alison

LikeLike

Amazing post! Travelling is the best teacher as well as a meditation itself. Especially when it is a historic as well as a scenic experience. The glory and aesthetics of a place can only be understood by being at that place and feeling the particles it is made up of. Thank you so much for sharing it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Aishwarya, and you’re welcome. Travelling seems to me to be a continual revelation. I would think it’s almost impossible to not learn from it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I completely agree to what you believe Alison, its the only teacher on which money spent makes us richer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very fascinating account of Jordan Alisa and Don… It is definitely next on my list now. Will connect with you guys for more detail. Keep inspiring us….

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much. Jordan is a rich and fascinating country, definitely worth visiting.

Alison

LikeLike

What a wonderful post 🙂 Hope you liked your trip to Jordan 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Dima, I’m glad you enjoyed it. We loved Jordan, especially Petra of course, but there was much else that is wonderful. I will write several more post about our time there.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that it’s very nice that you decided to travel and thank you for sharing it with us. it was a wonderful post

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Kyle, and you’re very welcome. I love sharing about our travels.

Alison

LikeLike

The pictures of Jerash and the mosaic map are amazing. I’m learning New Testament Greek. Maybe one day, I can read off the map without any help. Would you two like to go back to Jordan?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Jonas. Jerash was fascinating, and I do wish I’d understood the map a little more while I was there. I imagine one day you’ll be able to read all the inscriptions on the map. That would be amazing! I would like to go back to Jordan for two things – to spend more time in Wadi Rum, and to hike in Wadi Ibn Hamad.

Alison

LikeLike

I wanted to say that your blog is really great! Such an amazing decision you two took to travel the world and see it with your own eyes. I have been to many of the places you are describing (and lived is a number of them), and your view of them is very different, very insider’s and very unique! Will keep on reading you from now on.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Natasha. We do try to get a bit under the surface of the places we go to, and have ended up living in a few for at least three months or more (Tiruvannamalai, India, Canberra, couple of places in Mexico, etc) so we get a better feel for a place. I looked at your blog. It’s wonderful. I see you too have had a life of change and adventure, living your dreams.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incredible sights! 🙂 Did it spoil it for you being part of a tour group? Sometimes you just have to be kind to yourself and take an easier option.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jordan was amazing. Petra was the highlight of course. I’ll write about it soon. We’re not nuts about being on a tour. It was great to have everything taken care of, and to have company and to actually socialize, but of course you don’t get to linger, or make spontaneous choices, and we were rushed through Wadi Rum for no reason so we never got to experience just *being* in that extraordinary landscape. It’s all swings and roundabouts I guess, but a tour would probably not ever be our first choice. We did a tour in Egypt for security and it was fabulous. And when we finally get to China we’ll do one there too probably simply because I’ve heard from experienced travellers that travel there is really difficult.

Alison

LikeLike

That’s much what I thought. 🙂 When do you anticipate China, or is there not a set time limit? I’m full of envy but I don’t have the kind of partner with whom this would ever be possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We’ve more or less blocked out a plan that takes us until the end of 2017, so sometime after that. We have to be in BC for 5 months of every year to maintain our provincial health coverage so the next 5 months of this year in BC then Yucatan/Cuba/Central America, back to BC for a couple of months then next summer Spain/Morocco/Portugal and walking the Camino.

A.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow !!! 😮😮😮

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, yes, it’s a pretty amazing place.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes ! I am delighted 😍 Super photo! 👌

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s amazing, wonderful pictures as well. Sounds like you had an absolute blast. Loved reading about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Alexis, yes we did have an awesome time. I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like you, we love independent travel where we can go at our own pace and decide when, where and what we want to see. However, I can also understand how wonderful it would be to let someone take care of the myriad of tedious details, avoid the almost certain unexpected glitches along the way AND schlep our bags! No wonder you say, “Luxury!” I expect we’ll be signing up for more tours to areas that are difficult to travel in or so foreign that they;ll serve as an introduction before we figure out things on our own. P.S. Love the photos of you and Don – Makes me want to say, “look Mom, no hands!” Anita

LikeLiked by 1 person

We will almost always choose independent travel I think, except where it feels unsafe or just way too much hassle. I have two sisters who are very experienced travellers and they recently went to China. Both of them said how difficult it was so we’ll probably do a tour there. We did a tour in Egypt for security reasons and it was fabulous.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison and Don,

Since I love adventure and independent travel like you two do, I would like to see you write a blog post of what would make a perfect tour for you. Maybe using your Egypt tour as an example.

I know that you’ve written (and I’ve read) much about your Egypt trip. And about the tour operator you chose. My thinking for the blog post is what criteria would someone like you or I use to find a tour operator that works for the kind of travel we like? What kinds of questions should we ask of the tour operator?

Looking forward to your take on this.

Cheers,

David

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmmmmm. I’ll think about it. There are so many factors that come in to play. The short answer is that the perfect tour for me would be to be able to go where I want when I want but have someone else dealing with travel arrangements and act as a guide – i.e. have everything taken care of but also have room for spontaneity. I think in India it may be possible because there it’s economically feasible to hire a car and driver to take you wherever you want to go.

There’s so much more to it than this little fantasy of course. I’ll think about it.

Alison

LikeLike

Wow! I wish you could see me leaning into my computer screen with my wanderlust meter climbing steadily. It seems that a tour is an excellent idea in this case. I agree it is a great load off when not having to think about anything besides enjoying it all. Floating in the Dead Sea looks surreal. One wonders if it might just pop you back on your feet you seem so buoyant. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! I’m like that with your blog and other travel blogs! My wanderlust metre is constantly climbing. Sometimes the metre isn’t big enough. I think it’s a sickness. But I don’t want a cure 🙂

There’s always a risk with tours, but we went with reputable companies in both Jordan and Egypt. Jordan was overall wonderful but I had some complaints. Egypt was extraordinary from start to finish. In both cases I loved not having to deal with logistics.

Floating in the Dead Sea really is surreal. You should go! 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

The mosaic looks pretty amazing. I bought a book a few months ago containing historical maps and it is really interesting to see how land was once perceived– how differently than the way we perceive it today.

The picture of Jerash with the staggered columns in the foreground, and the echoes of the geometry in modern housing in the background is pretty amazing, especially when you think of the distances in time that lie between. Perhaps life was not really all that different in terms of its fundamental inner qualities.

The chocolate and vanilla custard sounds quite good also. Very fundamental. 🙂

Peace

Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I said in the post it took my research after seeing it to get it about the map – it’s really quite extraordinary but I didn’t much appreciate it at the time. The picture of Jerash you mentioned is one of my favourites. I love the juxtaposition of the two completely different eras, and the link – that life was not very different then at all, especially in its fundamentals.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Alison, just another wonderful post, and your photos are again just marvelous. Love the lizard shot! And the color in the first sun shot. And the next shot of the columns! I can understand your hesitancy for tours. I usually do not like them. But for a place like Jordan, it was probably a good call. One time when I was in Jordan, just after they first opened the border between Jordan and Israel, I crossed the border, taking a bus over the Joran River. THAT, the river, was one of the biggest disappointments of my life—there was no Michael rowing no boat ashore any more. The river was barely a trickle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks BF. I was excited to see the lizard – well I always get a rush out of seeing any kind of wildlife, especially when I get to photograph it. I blame Photoshop for the colour in the opening photo 🙂

We didn’t get anywhere near the Jordan River, but I understand your disappointment. I’m sure I’d have felt the same.

The only problem with tours is that once you’re in a country you find out about stuff that you’re not going to get to see – like hiking in the apparently green and lush Wadi Ibn Hamad. I almost would go back for that.

Alison

LikeLike

Floating in the Red Sea… quite humorous Alison with your fighting to stay upright and Don looking so laid back. So much history in the area. I would love to visit someday. I always like Greek and Roman ruins but I think the lizard stole the show! 🙂 –Curt

LikeLiked by 1 person

Um, that would be the Dead Sea. the Red Sea is yet to come 🙂

Don seems to have mastered the dead sea float. Me not so much.

The whole area is steeped in history – thousands of years. Definitely worth visiting, but I have to agree about the lizard. He was one of my highlights of Jerash.

Alison

LikeLike

Oops, I knew that. 🙂

LikeLike

Ahh! at first I felt pretty long blog . I came across many long blogs and they were boring but this post is awesome.. Its more about adding to the knowledge. Thank you for sharing vast information..Truly this was all an amazing history and you have written it perfectly..The photos are also good. Thank you for including history,travel guide,photos, music and of course plenty of knowledge…And last thing Map !!.. I love maps too .Thank you providing those details too.. You are really a cool writer 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Alexithymia. I’m glad you enjoyed it. It’s good to hear I put in just the right amount of information. All three places were really wonderful to visit.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post Alison! Indeed the mosaic map is so fascinating.. Good it did survive after so many years, even though not entirely. I love the pictures with you and Don floating in the sea!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Christie. I’m so pleased that I found out about the map. I appreciate it so much more now than I did when we were there. Floating in the Dead Sea was really a remarkable experience. I’m glad we got to do it.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your photos! Makes me dream of travelling!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lucy. I hope you get to travel one day. Make it happen, it will change everything.

Alison

LikeLike

Incredible post!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much. Glad you enjoyed it.

Alison

LikeLike

That map of Madaba is something else. I would have spent way too much time studying it. Thanks for including some pictures. A brochure would have been nice. I find in many of the historic sites here in Spain there is a lack of brochures or information too. But then they don’t charge to visit many of the sites, so I guess it’s a trade-off. The ancient Roman city of Jerash reminded me a bit of Pompeii. You both look very relaxed floating in the Dead Sea. All extremely fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Darlene. I wish I’d known more about the map when I was there, but it was a good journey of discovery afterwards. We never did get to Pompeii. We were staying in Positano and the day we decided to go the road was closed due to a landslide, but Jerash was pretty amazing, as was floating in the Dead Sea – that was an experience!

Alison

LikeLike

Just out of curiosity I googled the origin of the bagpipes and came up with a couple of interesting links: http://www.bagpipehistory.info/ireland.shtml and – from Wikipedia – “The evidence for pre-Roman era bagpipes is still uncertain but several textual and visual clues have been suggested. The Oxford History of Music says that a sculpture of bagpipes has been found on a Hittite slab at Euyuk in the Middle East, dated to 100 BC. Several authors identify the Ancient Greek askaulos (ἀσκός askos – wine-skin, αὐλός aulos – flute) with the bagpipe.[2] In the 2nd century AD, Suetonius described the Roman emperor Nero as a player of the tibia utricularis.[3] Dio Chrysostom wrote in the 1st century of a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe (tibia, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek and Etruscan instruments) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder beneath his armpit.[4] It has often been suggested that the bagpipes were first brought to the British Isles during the period of Roman rule.[2]”.

I have no doubt that the pipes you photographed came via the British, but they were probably a re-introduction of a tradition that flourished here long before it did in Scotland and Ireland!

P.S. Love the first image in this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Helen. Wow, that’s amazing. I would never have thought they were a re-introduction, from antiquity no less, though I must admit I didn’t think to pursue the origin of bagpipes.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person