19-22 March 2015. Driving from Rotorua back to Taupo we are drawn to the landscape in the distance. Clearly it’s time to go exploring. A sense of freedom comes from having a GPS since there is no fear of getting lost. We drive where our senses pull us, and then, when we’re ready, we enter in the address and let the disembodied voice lead us home.

We can see unusual hills off the highway and head up a side road to get closer to them.

It’s lovely countryside, but what we find that’s really interesting is this:

There are hundreds of them. We stop the car and watch them for a long time. Even though we are quite far away, and barely moving, they become aware of our presence. They start running. They come from our right, more and more and more of them, running up the hill, then down again to join the rest of the herd. We are astonished by how many they are. Hundreds. All rushing to be together with the herd. Later I read that deer are easily disturbed, and so it seems. Eventually they all settle down and walk off into the distance, away from us.

Large-scale commercial deer farming actually started in New Zealand. Deer are not native to the country, but were introduced for sport hunting in the late 1800’s. Their numbers rapidly multiplied and by the mid 1900’s they were regarded as a pest because of their impact on native forests. The export of venison from wild deer began in the 1960’s, and by the 1970’s industry pioneers began capturing wild deer and farming them. The industry has grown to 2800 farmers and 1.1 million deer. It is the largest source of farm-raised venison in the world, selling mainly to well-established markets in Europe. A national pest has become a source of income.

********************

The one thing the world will never have enough of is the outrageous. Salvador Dali

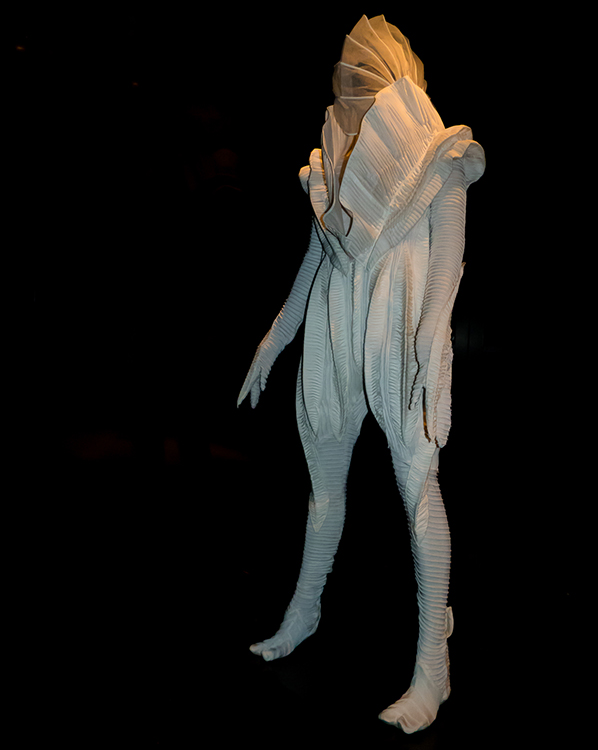

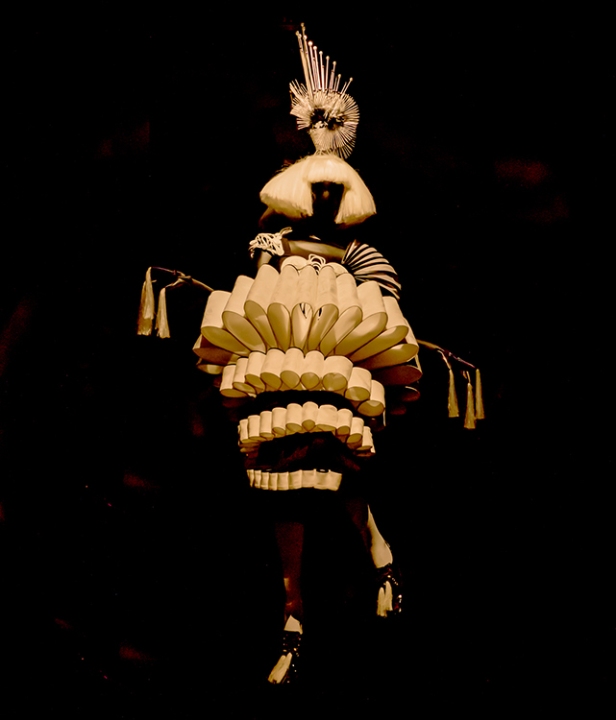

In 1987 in a country cottage near the town of Nelson a fashion show was held. It was no ordinary fashion show. Artists and designers were invited to create wearable art. It was the passionate dream of sculptor Suzie Moncrieff. From that small beginning it has grown into one of the biggest and most prestigious art and design competitions in the world.

Every year hundreds of entries arrive in Nelson for the initial selection. Those that are chosen participate in a unique choreographed music and dance performance while competing for highly respected awards and $165,000 in cash prizes. Having grown far too big for the town of Nelson, the annual two-hour World of Wearable Art spectacular is held in September in Wellington and runs for fifteen performances seen by nearly 50,000 people.

We’d heard of the World of Wearable Art museum in Nelson with its rotating collection of the best entrants in this annual extravaganza, and planned on going. We really should write these things down. Nelson came and went and we realized we’d forgotten to go to the museum. Upon further investigation we discovered there was an exhibition in Auckland, but it was finishing in a few days. So we did a lightening overnight trip from Taupo to Auckland to see it before it closed. WOW!

A sign at the exhibition:

A wilder kind of wardrobe

In 1987, WOW founder Dame Suzie Moncrieff had an idea – she would get art off the walls and onto the body. Over 25 years later, thousands of makers have translated her vision into their own unique pieces of wearable art.

These spectacular creations from WOW’s archives prove that the only limit to wearable art is the artist’s imagination. Some come from a technical challenge. Some show everyday materials transformed into something extraordinary. Some are aimed to simply delight the eye.

WOW’s judges look for originality, creativity, and skill in construction.

Categories include the Open Section, clothes for children, Avant Garde, Cultures of the South Pacific, Bizarre Bra, and Creative Excellence.

The garments don’t have to be commercially viable. They don’t have to take themselves seriously. They just have to be wearable. Dame Suzie Moncrieff.

Lobster Woman was definitely one of my favourites.

The exhibition that we attended will be in Seattle from March to September 2016.

********************

Twenty-two kilometres of narrow winding gravel road, known as the 309, crosses the Coromandel Peninsula from one side to the other. According to Wiki, deaths are common among those who don’t know the road. We go exploring. We want to get to the other side of the peninsula for the Driving Creek Railway. It seems way more interesting to take the 309 across rather than the highway up and around. And so it proves.

We’ve driven about three quarters of the way, through beautiful green countryside, from the sea at Whitianga, up and over the ranges towards the sea at Coromandel Town. Suddenly up ahead we see pigs at the side of the road. Pigs. Many of them. Pigs of all ages, from tiny little squealers to large adult males. Sixty-two pigs to be exact, roaming and rambling at will, and in their midst several chickens and a barefoot curly-haired man, all grubby sweats and plaid shirt and smiling bright eyes. So we stop of course and have a long conversation with Stu the Pig Man.

Stu lives in the bach. He gestures to a corrugated building across the road from where we are standing in amongst the pigs. In New Zealand ‘bach’ is short for bachelor pad, meaning a one-room home or apartment.

Next door to the bach is the family home where his brother lives with his wife and child. The tract of land, nine hundred acres, was acquired by his father shortly after the second world war. The pigs are feral, having descended from the pigs brought to New Zealand by Captain Cook in the late 1770’s. Wild pigs proved to be just as destructive to the New Zealand native forests as deer, and are openly hunted. But not by Stu.

He doesn’t raise them for food or for sale. These pigs are Stu’s pets. All sixty-two of them.

He knows them all by name. He talks about the sow and her piglets, pointing out that the bigger piglets are actually the offspring of another sow, but they push in and suckle from the sow that most recently gave birth. It’s not fair but what can you do?

In the winter the pigs live in the bach with him. He says they keep him warm. He also has a satellite dish hooked up to an old trailer. When he watches TV the pigs come in there too.

At one point during our conversation one of the locals stops to give Stu some old bread. In a heartbeat all the pigs are crowding around him jumping up to get some.

Stu is clearly a happy man. His bright eyes smile as he looks directly at you, his love for the land, for the earth, for every one of his pigs is palpable. There is no guile, no pretensions, no caring about social norms. What there is, is a big smile, an open heart and gentle kindness. His quiet joy is infectious and we feel lucky to have met him. And his pigs.

We knew nothing about Stu beforehand but discovered later that he is actually listed as an attraction on the Coromandel Town website.

Next post: a tiny hand-built railway in the mountains. If you build it they will come.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted.

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2015.

Paul and Rebecca have also written about Stu on their blog movin2newzealand

I have the Seattle show dates on my calendar now. WOW indeed!

I’m glad there are still people like Stu The Pig Man on our planet: gentle souls living out their lives in peace and joy. Wonderful.

LikeLike

Isn’t Stu a delight?! And yes, do make the trip down for WOW – really amazing. I’m sure you won’t be disappointed.

Alison

LikeLike

Wonderful post — art, nature, personality. Beautiful photographs, too! Can’t wait to meet you tomorrow! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Kelly, glad you enjoyed it. Us too – looking forward to finally meeting!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW is the word Alison! For your post as well 🙂 That’s the largest herd of deer I have ever seen. And Stu and his piglets are a wonderful bonus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Madhu. That herd of deer was huge! Way more than can be seen in the photo. We were astounded by how many there were – maybe 500?! And yes, Stu was definitely a sweet unexpected bonus.

Alison

LikeLike

Indeed wow! Very cool post filled with unique things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Mani. New Zealand was full of unique things. We were frequently surprised.

Alison

LikeLike

I´m not sure what I liked best, the deer, the pigs, Stu or the fabulous wearable art! it was all amazing. I love these out of the way finds when travelling. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Darlene. We were thrilled to see the deer, and so many of them! And discovering WOW was amazing – definitely worth the quick overnight trip up to Auckland. What luck running into Stu and his pigs – we knew nothing about him. I too love discovering these out of the way things.

Alison

LikeLike

Wow indeed!! Great photos. ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paulette. We were certainly wowed! 🙂

Alison ❤

LikeLike

Awesome, I’m so impressed ☆★☆

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! I’m glad you enjoyed it all. New Zealand is a wonderful place to explore.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great pics as usual. When the wild deer yard up here in Northern ON in the winter, one can see hundreds at a time, but they are wild, not farmed. Are you guys back in country or still in NZ.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much. Seeing wild deer would be amazing. We’re back in Canada and leaving again in about 2 weeks. The blog is always (chronologically) about 4 months behind.

Alison

LikeLike

Love the deer! When we were in NZ, deer farming had just started. There is a funny story around the deer that I will share soon on my site… stay tuned. Fabulous photos!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Shirley. Looking forward to your deer story 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

Heartwarming to read about Stu the Pig Man. Many people don’t know that pigs are actually very intelligent – they have exhibited an abstract intelligence in computer tests that is generally lacking in dogs (still remember the image of the pig in front of the computer screen LOL). They have been much maligned, largely because they are not good-looking in the sense that dogs, cats and horses are, and are seen as dirty creatures who roll around in mud – which they actually do to cool off in the absence of a cleaner water source.

Nice to see a person with regard for pigs who treats them well and gets affection back in return.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t he wonderful?! I agree pigs get such a bad rap, especially when they are so intelligent. Stu regards all his pigs as his buddies.

Alison

LikeLike

interesting.

LikeLike

Thank you so much mukul. I had a quick look at your blogs. I can see there is much to read there. We’ve been to India a couple of times and loved it. Such a rich diverse country.

Alison

LikeLike

thank you for your kind words and comments. its encouraging for greenhorn bloggers like me

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to echo Darleen’s comments. It’s all fabulous. Many thanks as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Roslyn, and you’re welcome! I’m glad you enjoyed it. It really was fabulous! New Zealand was a wonderful adventure.

Alison

LikeLike

Everything is WOW in this post Alison. Those deer and more deer and Stu and his pigs touched my heart, such a gentle person it shone from his eyes. I worked on a pig farm and I agree they are very intelligent and given the right conditions are very fastidious too. That wearable art!!!! WOW WOW WOW Your photos are so detailed and yes I think I liked the lobster outfit best. I’m looking forward to your next post as I have been on that amazing railway about 3 years ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks pommepal. Those deer were amazing. I’ve never seen anything like it. Must have been 500 of them! Stu is a total sweetheart ❤ and the wearable art was definitely WOW! It was a pretty rich few days. Well really all NZ was like that.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve never thought of piglets as cute but those are cute! And it’s awesome that they’re Stu’s pets and he knows all of them and in the winter they stay with him. Such heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aren’t they cute?! We just loved them. And Stu. What a beautiful soul he is.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great combination of photos, and experience! See, that’s what I love about your two: you make the effort to rush out to do something, like a museum–which I would never go to, and especially not rush out to. Maybe if I had a travel partner…? No bucks in the herd? I think I saw one with the beginnings of horns? The lobster dress is a hoot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks BF. I guess we mostly make the effort but not always. It’s because we get to a place and think we’ll probably never get back so we’d better go out and see what there is to see and do what there is to do. A travel partner would whip you into shape in no time 🙂

We’re putting together a kind of itinerary for Turkey sometime this week. If you do end up coming to join us for a bit we’ll get you moving. Or not 🙂

No bucks as far as I can tell. Seems weird to me. Maybe they keep them separate.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cool. Send me your itinerary when finished, I’ll see if any of it aligns with my time off! Would be cool to meet up somewhere.

And no bucks. You think maybe does taste better?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post and very nice photos of the pigs! We actually went to WOW in Wellington this year and it was everything you’d expect. Thanks for mentioning my blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paul. Stu and the pigs were such a delight. What a lovely man. How fabulous that you went to WOW! I would love to go, so maybe we’ll go back to NZ one year in September. Just from what they were screening at the exhibition in Auckland it looks amazing.

Alison

LikeLike

This post just jogged my memory, reminding me of a trip we took to the islands of Haida Gwai (previously the Queen Charlotte Islands) some years ago. Deer had been transported to the island and flourished in the absence of a natural predator, replicating substantially and coming to be seen as pests – much like the situation you describe.

At every turn it seemed we ran into Bambi and her babies. We saw way more does and fawns than we saw people. They were everywhere. But where were the bucks?

I might not remember this if not for arriving back on the mainland (Prince Rupert) and driving up a street on the hill. There were two huge bucks, just walking nonchalantly up the hill in the middle of the road! I said ‘aha, that’s where the bucks go – to town on a Saturday night’!!

In case – still wondering where the bucks hide or go. . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I never knew there were deer on Haida Gwai. That’s bizarre that the bucks would be on the mainland – perhaps they swim to and from the islands. To go to town on Saturday night! Chuckle. I’d love to see them!

Alison

LikeLike

Amazing pics! I love the deer pics they are such beutiful animals and so nice to see them walk free. Here in the city all animals except thr pigeons are under some form of captivity.

I hope the exhibition comes to holland too. Such witty and intrinsic designs!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mr T. We loved seeing the deer, and the pigs too. Sweet unexpected surprises. I don’t know if the exhibition is going to Holland. If you look on their website, which is linked above, it lists the tour dates. It’s currently in Brisbane.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mouth truly gaped open at the first wearable art photo – that horsey, leathery outfit defied description (the heavy head and basketball-shaped skirt on a slender model’s body … I’m still trying to absorb that!), and the lobster dress was equally mind-blowing! The whole WOW segment threw me for a (good) loop after all those graceful deer. Stu and the pigs were the icing on the cake of this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t that horse outfit amazing?! I too was gaping, trying to find a way to process such an image. And also the lobster – so creative! I nearly didn’t publish the lobster tail – very low light, and I didn’t want flare from using a flash so the picture was pretty bad. I had to do a lot of work in Photoshop to make it usable – really glad I did because it is the only way to really show the complete outfit. And somebody actually walked in that outfit in a show!

We’d only read about WOW, and knew there was an exhibition in Nelson that we promptly forgot about. So glad we made the trip to Auckland to see it.

And the deer and Stu and his pigs were two lovely unexpected delights from going exploring.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am chuckling away at the little gifts that travel gives. I am also thinking that my jeans and sweatshirts are a bit dull, and maybe due for a change!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s one of the reasons I love to travel – you never know what you’ll find around the next corner. I think you should trade your jeans and sweatshirts for the lobster outfit – so much more stylish 🙂

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

GPS is a great invention and sounds like you have made the most of it on your road trip in NZ. WOW for all your great pictures and thanks for introducing us to Stu and his pigs, I loved that he has them as pets.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Gilda. And you’re welcome! Stu is such a kind gentle soul, it was a pleasure to meet him. His love for his pets was very obvious. We loved having a GPS – we borrowed it from my sister, but now will get our own – so handy.

Alison

LikeLike

That is a strange mix of things to see on one road trip, although I don’t see what the big deal is about the clothes – it looks like the stuff I wear everyday. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a strange mix isn’t it? The deer and pigs were total surprises. The clothing – well I think I’d better head up to Alaska to check out your wardrobe 🙂

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fun and diverse post. The deer are lovely, Stu and his pigs interesting and the Wearable Art is mind blowing. You come up with the most amazing things. Love your blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Eileen. We just poke around wherever we are – the world is an amazing place. The deer farm and Stu and his pigs were total surprises, and we too were blown away by the wearable art.

Alison

LikeLike

Hmmm. I’m not sure how I feel about the wearable art, but those pictures of the herds of deer are quite amazing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well I do admit that the wearable art is seriously eccentric and weird. Some I liked, some not so much, but I agree with Dali – can’t have too much of the outrageous 🙂

We loved the deer – such an unexpected treat.

Alison

LikeLike

Stu. Definitely Stu. Shoeless, weathered Stu. A total delight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t he wonderful?! We had such a lovely time with him and his pigs.

Alison

LikeLike

You see the most outrageous things on your journeys! Love the story about the pigman and his pets. And those outfits! I will definitely have to see that exhibit when it comes to Seattle.

I’m leaving for Salmonberry in a few minutes. Ahh….! Love, Kay Oh – Don: I finally got my new nook registered and am learning how to use it. I’ll use it at Salmonberry. Thanks for the gift!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Kay. I guess we seek out stuff, like WOW, but Stu and the deer we were just going exploring – always fun.

Have a wonderful time at Salmonberry.

Alison

LikeLike

Good to hear that you were able to get your Nook registered and that you can begin using it at Salmonberry. Lots of good reads ahead for you. Much love, Don

LikeLike

A stunning reflection on the vivacity of this realm… The art was astonishing to me, and I think I liked the warlock of collage best in some way– the horned assemblage of hearts, diamonds, hints of phoenix and dragon, and the scorpion for a shin guard. I’d probably put that one at center forward, put the headless horsemen meets Cinderella in the mind of a boat builder in goal, the horse head spear-thrower on one wing and the rockette who ripped the steering wheel out of her rocket on the other. Stu would be the coach of course, and the pigs should clog up the midfield quite nicely.

Michael

LikeLiked by 1 person

But what about Lobster Woman?! You left out Lobster Woman! She could slash her way up one side and down the other, taking out anyone with a flick of the tail 🙂

We also found the art astonishing, and were very glad we made the trip to Auckland to see it, and may even head down to Seattle next year to see it again. Or go to back NZ to see the entire show. The exhibition included wall size videos of clips from the shows in Wellington – a magnificent creative extravaganza. What we saw was just the tip of the iceberg, and the photos here no more than an ice cube in your drink.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve just discovered your blog, wow what a wonderful life you guys have! I love the scenic photos of this post, absolutely beautiful and so atmospheric.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Emily. Welcome! New Zealand is a very beautiful country. Everywhere we went was gorgeous!

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, New Zealand is on the wishlist if only to see the beautiful landscape from that first image. -Ginette

LikeLiked by 1 person

For sheer beauty New Zealand is probably the most beautiful country we have been to. Check out this post:

Alison

LikeLike