5-12 December 2014. We are sheltering under a banana palm in the desperate hope that its broad leaves will protect us from the rain.

The rain had started softly a while back, so we’d taken shelter under some trees. It seemed to ease so we continued walking until it got heavier. Stopping under some trees again we thought maybe we could wait it out, and then it came. Sheets of rain, torrents of rain, rain so heavy and thick and unrelenting you think you might drown in it. We make a dash for the banana palm. Its protection is tenuous at best. I suggest to Don that we run back to the house we just passed in the hope they’ll give us shelter. Our cameras are tucked away in their cases. I have my broad-brimmed sun hat pulled down tight on my head and clutching my camera bag close to my chest I bend my head forward in the hopes the brim will give some extra protection. We sprint back to the house and walk quickly, completely sodden, through the garden to the front of the open-sided building. In the few seconds it has taken to get to there we are wet through, trailing streams of water, backpacks saturated. At least our cameras are dry.

We are immediately welcomed inside. We stop to take our shoes off but are told it’s not necessary. We are ushered into two Adirondack-style chairs and within seconds a child runs to us with a towel. It’s not the cleanest towel I’ve ever seen, but compared to some we’d seen in India it is very far from the dirtiest. We are grateful to have it to wipe of the worst of the water. About ten minutes later another child appears with a pristine white towel that he shyly hands to us. Sweet hospitality.

We find ourselves in a fale (pronounced fah-lay), a typical Samoan home that is open on all sides except for supporting pillars. There are two women in the room. The older one, the grandmother, sits cross-legged on a bench across the room from us. On the floor in front of us her adult daughter is crafting the colourful wool edging onto a sleeping mat. She works with the ease and speed of someone who has done this all her life, knowing exactly which piece of leaf to choose next, which way to bend it, which way to attach the wool to create a smooth finished trim. They both speak English. Almost all Samoans learn English from a very young age along with their own language.

The fale we are in is the home of the grandmother, and seems to be something of a family living room as well.

Behind it is another fale for the daughter and her husband, and adjacent is a third for the children.

I ask about the sleeping mat, if it is for sale, but no it’s for family use. It is made from laofala leaves, a name I’ve not heard before. Later I learn it is pandanus. The leaves are soaked and then dried in the sun before being woven into mats, hats, baskets and other items.

I ask the woman about their life. She says it is a very peaceful life. She has seven children. Earlier when we’d walked past we’d noticed some of them were weeding a patch of land in front of the fale. It is for planting peanuts we are told, that will be sold or traded around the island. We are shown a huge bag of seed peanuts. The family also grows pumpkins and other vegetables for their own use and for trading on the island. No doubt their diet also includes a variety of fish and seafood.

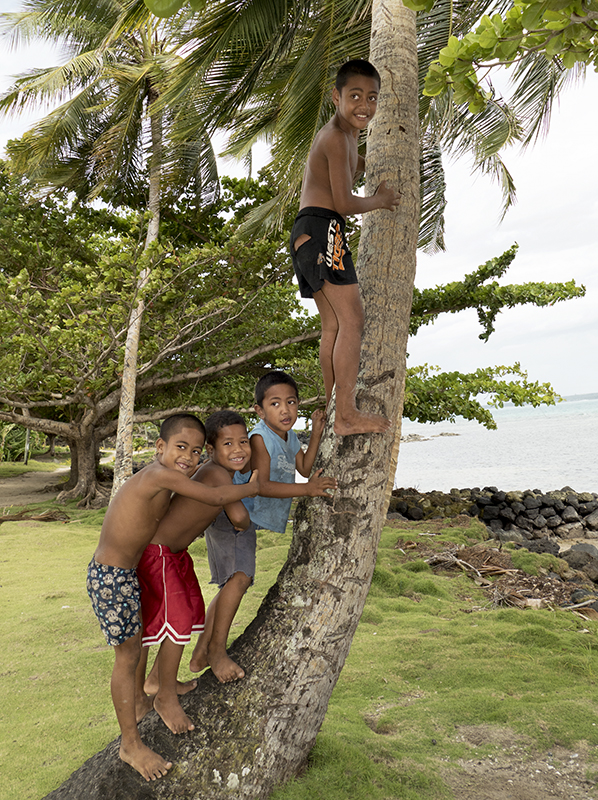

As you can see, the girls continue with their work. The boys, younger, and mischievous, are more interested in mugging for the camera.

They are all oblivious to the mud, and to the rain, which continues to pour down. Later when any of them come to the house I notice there is a small plastic tub of water by the entrance which they use to wash the mud off before coming inside.

We are on the small island of Manono, a twenty-minute boat ride from the west side of Upolu, the main island of Samoa.

Manono has four villages ringed around the coast and is the third most populated of the Samoan Islands. It is advertised as having no dogs and no cars. Apparently the wild dogs of Upolu have a reputation for their ferocity although we are hardly aware of dogs on Upolu, let alone any that are ferocious. You can walk around Manono in two and one half hours. The path looks like this:

and this

and the jungle pictured above, and at times goes by the beach and the ocean. Our trek was halted by the rain which we blessed, giving us, as it did, a chance to visit with one of the families of Manono. We are also slowed by talking with people, and by taking in our surroundings, and by photographing all the enthusiastic children who push to be in front of the camera. It takes us four joyous hours.

The two boys on the ground were so excited about pushing in and mugging for the camera that they fell over in a heap.

The boy in black shorts suddenly shimmied up the coconut palm. Before I could even get a shot of him others had rushed to join in the fun.

Meanwhile the older kids are more interested in playing volleyball.

Playing by the beach.

The men of the village work together to build a new house.

The large fale on the left is probably a meetinghouse for the matai or village chiefs.

‘Too cool for school’

Samoa is a traditional Polynesian society, and fa’a Samoa, or “the Samoan way” continues to be the central component of village life. Apart from the 35,000 people who live in the capital Apia, the people of Samoa live in villages by the sea circled around the islands of Upolu, Savaii and Manono. There are over 360 villages. Each village is made up of extended family units called aiga. The head of each aiga is a matai, or chief. There are 18,000 matai who make the laws for the villages, with a lot of influential input from the women’s committees. Only the matai can be elected to the Fono a Faipule or Legislative Assembly. The matais are treated with great respect and deference. We were told that there is a second more formal way of speaking in the Samoan language that is always used when speaking to the matais. The two buildings most central to village life are the church, and the meetinghouse for the chiefs. Samoa is not a wealthy nation, yet it seems to be a well-organized, thoughtful, and peaceful society. Family is paramount. Everyone is taken care of.

Driving around the island of Upolu we are struck by the beauty and neatness of the villages. Everyone makes gorgeous garden hedges. I also noticed that every village, every home, has electricity.

We walk along the cliff trail in a national park on the south coast through a pandanus forest,

and are treated to some spectacular scenery.

We hike in to a waterfall, one of many on the island,

and are stopped again and again by the profusion of exquisite flowers in this endless lush environment.

Almost everywhere we go we are met with warmth and smiling faces.

We go swimming here!

It’s a lava tube that connects with the ocean. Lava tubes are formed when the less viscous surface lava from a volcano hardens and forms a crust making a roof over the slower-flowing thicker lava. Eventually the lava flows away leaving a hollow tube. This one on Upolu is called the To Sua Ocean Trench and is about thirty metres (100 feet) below ground level. At high tide it’s deep enough to dive from the platform, but we are there at low tide so we can touch the bottom in some places.

Okay. Truth. We are actually spooked a bit about the climb down the extremely steep stairs and even steeper ladder, but then we remember

the tree in Western Australia, as tall as a sixteen-story building, and know we are not going to miss this opportunity. In the end the climbing is easy, and the swimming sublime.

In the third and final post about Samoa: a riotous noisy Christian church service held at the local gym, and a performance of traditional Polynesian dances including the spectacular fire dance.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2015.

The village scenes remind me so much of the small villages on Fiji’s Yasawa Islands. I adore the Polynesian culture but didn’t appreciate it growing up in Auckland.

LikeLike

We didn’t get to the Yasawas so nice to know we’ve already seen something similar. We have 2 more days in Fiji on the way back to Canada so maybe we’ll go then. I also am a fan of Polynesian culture.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful post. Wonderful place. Wonderful people so connected to nature. Lucky ya’ll. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Paulette. Yes it is a wonderful place – warm climate, warm people. Very Lucky!

Alison

LikeLike

How amazing to think of living in a fale – a home with no walls and, most foreign of all, no locks! Your photos are gorgeous and show a utopia that I’d love to visit someday… Anita

LikeLike

Thanks Anita. I guess I hadn’t thought of the no locks thing – I can’t imagine it being even the slightest problem in their society. Hope you get to visit.

Alison

LikeLike

Beautifully written and photographed!

LikeLike

Thanks so much Cindy.

Alison

LikeLike

For some reason, the “like” button isn’t working. I’m getting an error message about security and certificates about the site. I know there isn’t a problem with your site or with wordpress, and this issue didn’t happen for any previous posts.

Anyhoooo… I can’t use the button, so…. LIKE. 🙂

This looks like a beautiful place, one I’d enjoy visiting.

LikeLike

I just read some forums about the “like” button issue. One suggestion was to try a different browser. It worked in Safari. Normally I read your blog in Chrome, don’t have the issue, so either the Like widget or Chrome have made some changes since your last post. Oh sigh.

(However, I keep getting asked to log in using Safari — one to do my “like” and now again before I can post this comment. Safari also threw me a note about the site certificate — it said that the wordpress certificate is invalid.)

LikeLike

That’s all very weird. Apparently no-one else is having trouble with the like button. The site certificate thing might be related to the fact that we’re now alisonanddon.com, not alisonanddon.wordpress.com?

Whenever I’m having trouble with WP I always start with logging out and clearing cookies. It always helps.

Anyway thanks for the LIKE!

Alison

LikeLike

The rain really was a blessing. What a beautiful island and beautiful experience!

LikeLike

Yes it was. And I kept putting out to the Universe that I wanted to meet some people and see their home and be able to ask about their life, and have more of a connection than a passing hello. It was the rain that did it. I don’t think we’d have just walked in to a home without that excuse. It was a wonderful experience.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always enjoy your posts and this was no exception. Fantastic.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Anne.

I’ve been exploring your fabulous blog – so much useful information. Definitely going to look into Priceline bidding!

Alison

LikeLike

Ahh, so fun to see the colors and warmth, of both the scenery and the smiles! Having just returned from a COOLLDD trip, I am soaking up the warmth of yours. I loved the story of getting caught in the rain and its serendipitous outcome.

LikeLike

Thanks so much. Happy to share the warmth.

You’ve been in Russia and Estonia in January! Brrrrrrrr, but I bet it was fabulous.

That tropical downpour was such a blessing. I so much wanted a closer connection with the people who live there, and it gave us the perfect excuse.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was surprised in Bali by all the rain this time of year. Because usually in summer, they have the monsoons. The guy who owned my villa said there were two monsoon seasons. One of them is about the time you were in Samoa and I was in Bali. Is this true, you think?

I’ve wanted to go to Samoa ever since I heard they had a university there…but I think that was in American Samoa. Still, I wouldn’t mind teaching and retiring there. Was it cheap? It sounds like you both are carrying cameras?? And still getting the “peace” sign (v-fingers) in some of the photos, which as usual…oh, I’m not even going to say it again!!!

LikeLike

I have read about two monsoons in some parts of SE Asia, but can’t remember any details. When is summer? Which hemisphere are we talking about here?

It wasn’t cheap, but not outrageously expensive either. We don’t do backpacker type travel. Yes we both have cameras – always have. Every time I get an upgrade Don gets my old camera so he gets an upgrade too.

Seems we get peace signs everywhere we go these days. All the Japanese do it for sure, but many many other places too.

Alison

LikeLike

enjoyed much your

wonderfully expressed adventure

in Samoan paradise 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much for

wonderfully expressed comment

in blogging paradise 🙂

Alison xox

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love these little vacations you give me wherein I get to see and learn something of another culture without all the pesky luggage and security pat downs…

LikeLike

Thanks Leigh, and you’re very welcome 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

This post swept me back in time to a wonderful trip we had to Tahiti in 1984, joining friends on their boat, which they had sailed there from British Columbia. We sailed with them to Raiatea, Huahini, Moorea, Bora Bora and Ta’ha’a (I’m sure I’ve forgotten all the correct spellings). The rain, the paths and roadways, the hedges and flowers, the homes and beaches, and the smiling hospitality of the people … it was so much like this in the Tahitian islands back in the ’80s. I wonder how it is there now. When I get home, I have a yen to find my slides from that trip! Thanks for the lovely journey.

LikeLike

Thanks Silk. Your trip sounds absolutely idyllic and fabulous. I’m sure it is different now. We looked into stopping in the Tahitian islands and it was horrendously expensive. Hope you’re still enjoying NZ.

Alison

LikeLike

Fascinating post – beautiful pictures. Such an idyllic life. Although we have so much here in the modern western world, I think cultures such as the one you describe here are much richer in certain ways.

Is the cloth around the pillars used to close up the homes and give privacy at night, or are they left open all the time? In which case, do they have private spaces for intimate encounters? For having babies?

Also, I’m interested in the status of women in Polynesia. From my understanding, Polynesian cultures are traditionally sex-positive, and women have a lot of freedom, at least relatively speaking?

LikeLike

Thanks Gayle. I think their life is idyllic in many ways, but not without its problems. Dental care for instance seems non existent, and I don’t know what level of medical care they have. I know the country receives aid from Australia, NZ and I believe US also (though maybe that aid goes to American Samoa which is a different entity). But they seem to have plenty to eat, and a strong family support system, and electricity as I mentioned.

Yes, I’m sure the cloth drapes are used for privacy sometimes.

I only know about Samoa – men only are matais, and only matais can be elected to the national Legislative Assembly, however the women’s committees in the villages have a strong voice, and I don’t believe Samoan women are subjugated the way they are in other cultures.

Alison

LikeLike

Beautiful post! Gorgeous photographs and great to hear about your adventures. We hope to visit Samoa soon!

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I’m glad you enjoyed it. Samoa is definitely worth visiting, and so close to NZ. We’ll be in NZ soon 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

Although I’m in Malta, and experiencing my first taste of Mediterranean life, your description of Samoa sounds even more exotic. Although the scenery is, of course, breathtaking, I found myself very interested by your observation that everyone is taken care of, and that every house has electricity, and that society in general seems to be more family-oriented than most Western civilizations. Very intrigued to read your final Samoa post!

LikeLike

Oooooooo Malta! We have some friends who were there last year and said it’s amazing. Maybe a bit like Cyprus was for us.

Samoa’s definitely exotic, and beautiful, and peaceful, and easy. Worth a visit.

Alison

LikeLike

What a beautiful post & amazing photos. Always refreshing to see some tropical posts.

LikeLike

Thank you so much. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Alison

LikeLike

Woo! I really like your article. The pics are amazing! I keen on photography and they are so nice. I´d like to go there or a place like that sometime.

From now on I will read you. I am a Spanish girl who enjoys knowing world and reading about different places.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! I hope you get to Samoa, it’s lovely. And thank you for following.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is just incredible, Alison. Samoa looks like paradise and the photos have me itching to plan a trip to the South Pacific! Thanks to your post we have learned so much about the culture and way of life on those islands. In all my travels I have never seen houses like fale – it seems like such a beautiful way to live, completely open and receptive to nature. However it does have me wondering about privacy and keeping the weather or unwanted visitors (certain bugs and rodents!) at bay. Or perhaps we have become too cocooned in this respect.

You and Don were so brave to go down that impossibly steep ladder – I know I would be nervous! Parts of Samoa seem to come straight from a fantasy novel: the lava tube, that waterfall surrounded by the lush carpet of rainforest, the natural arches on the coastline… it is all so dreamy. As for the Samoan people, it seems like you and Don charmed them as much as they charmed you. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks James. I think you must make a trip to the South Pacific!

Most of the family compounds have at least one building that has walls, but generally people live in the fales. They use curtains for privacy. I was not aware of bugs being an issue – few mosquitoes, and nothing poisonous as far as I know.

We almost left without swimming in the lava hole. What a wasted opportunity that would have been! In the end it was easy, we just had to pay attention. And definitely worth it.

Samoa is a magical place, warm and friendly and lush. I’m so glad we went there.

Alison

LikeLike

Hi Alison, you looked very atletic coming up the steps of the lava tube. The fale houses looked very colorful and spacious, very interesting to have the oportunity to interact with the Samoans in such a relaxed way. Beautiful pictures, thorougly enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Gilda. I’ve been more athletic 🙂 but slowly getting fit again.

We were very lucky to have that opportunity to visit a home and interact with the people. Without the rain I’m not sure we would have.

Glad you enjoyed the post.

Alison

LikeLike

This post reminds me so much about Indonesia. We lived for three years on Java but worked on many islands. Your story about getting caught in the rain sounded very familiar. I recall several trips to Tana Toraja on the island of Sulawesi. Torrential rains followed an hour or less followed by brilliant blue skies and sunshine. Hospitable people like nowhere else. Beautiful memories of beautiful people. So happy to hear you too are privileged to have this experience. Thanks for the gorgeous photos.

LikeLike

Thanks Helga. Indonesia is on our list. We’ve not been there except for Bali. There’s something about the South Pacific tropical islands I think that seems so welcoming both the climate and landscape, and the people. We’re very glad we chose to go to Samoa.

Alison

LikeLike

What a wonderful thing that the rain washed you into the acquaintance of the family you met. Great photos of this beautiful place!

LikeLike

Thanks Angeline. Wasn’t that beautiful serendipity?! It was so lovely to get to speak with some people who live there, and learn a bit about their life.

Alison

LikeLike

Nothing like an encounter with real people

LikeLike

Yes I agree Ron, and sometimes it can be difficult, either because of customs and/or because of the language barrier, or just simple shyness or caution on our part. This time we were pushed into it in the most gentle, if somewhat damp, way.

Alison

LikeLike

Wow! I love stories like this. The unexpected blessed encounters which makes for a much better day than was planned. I love the photos. Makes me want to plan a trip there. Truth be told, I doubt I would have been brave enough to make it down that ladder!

LikeLike

Thank you so much. I hope you get there one day! That rain really was a blessing wasn’t it?! I’m so glad we made the decision to go down the ladder and swim in the lava hole – I think we’d have regretted it if we hadn’t. It felt kinda special.

Alison

LikeLike

I am so glad that i found your blog. Lovely well written post and photographs are amazing.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Diana. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Alison

LikeLike

Incredible! Looks so lovely. I just started my own travel blog so this is such an inspiration.

Jake- http://www.zeroborders.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Thanks so much Jake. Glad you enjoyed it.

You’ve made a good start on your blog!

There is a setting you can change (not sure where anymore, but you’ll find it in the settings) that turns your name at the top of your comment into a link to your blog.

Alison

LikeLike

Thanks for the great photo essay on Samoa, Alison and Don. As always, I enjoyed the pictures of the people… but I would go there for the scenery. Loved the flowers, waterfall, and the interesting island in the ocean. –Curt

LikeLike

Thanks Curt. And your’e welcome 🙂 It’s a beautiful place, worth visiting. Apparently there are many of those waterfalls, and the lush tropical jungle and flowers are everywhere, and surrounded always by the sea. It’s such a rich gorgeous environment.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Now we’re getting down to it! Loved the post and the images. I feel as though I’ve glimpsed another world, and it was waving back at me. So many smiling faces. Joy mixed evenly throughout the necessity, seamlessly. The lava tube swimming hole looked brilliant, and your travel legs must be strengthening if you were running through a deluge and scampering up and down ladders to swim in underground caverns!

Loved the image of the rocky outcropping amidst the crashing waves. And the boys falling over in their eagerness to be caught on digital…

Michael

LikeLike

Thanks Michael. Yes – many smiling faces, everywhere we went. And the lava hole was fabulous, and the endless beautiful scenery. It *is* another world, and a lovely one.

We definitely had out travel legs back in Samoa, then a bit of a set-back when we first arrived in Canberra, but regaining them slowly now.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful part of the world. I’ll pretend not to be jealous 🙂

Many thanks for the follow.

LikeLike

Yes, very beautiful. We’re so glad we chose to go there.

And you’re welcome! Looking forward to more of your travel stories.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terrific photos. Particularly love the one of the water hole/ swimming hole. Best part about travel: the serendipitous meetings and connections with people along the way which bring understanding to local culture and way of life!

LikeLike

Thanks Peta, and I agree – best part about travel is serendipitous meetings with the locals. I feel a bit guilty – that photo of the swimming hole is Don’s. I think it’s the only time I’ve not given him credit for one of his photos!

Alison

LikeLike

Dear Alison and Don,

You guys are such an inspiration. Reading your blogs makes me wait for your next. This one is quite a pick! I love the way how you have befriended your models before the click. The pictures are simply magnificent. My favorite is the scenic edge overlooking the sea with battling cliffs in the national park and the enthralling Lava Tubes.

LikeLike

Thank you so much David. Samoa is a wonderful place, and the people are very friendly and welcoming. The children especially love to be photographed. And the scenery is fantastic. Isn’t that lava tube amazing?!

Alison

LikeLike

Alison and Don, I am a creative director of a private label magazine and would love to talk to you about using some of your samoa images for an article on Samoa. If you could contact me at leeanndougherty@sbcglobal.net that would be wonderful. Look forward to hearing from you… Best LeeAnn

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi LeeAnn, I’ll email you.

Alison

LikeLike

Another wonderful post! I love how you capture the essence of each island with your words and your photos. Truly magical.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Heather. I’m glad you enjoyed it. Samoa is beautiful in so many ways. It really is magical.

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the first time I’ve read a travel blog about Samoa. I had no idea how beautiful it is! I really enjoy how you combine your words and photos to tell the story. Thank for you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Wendy, my pleasure. Samoa is a really beautiful place, and not that well known so retains much of its charm and magic.

Alison

LikeLike

What a interesting and culturally rich experience. How beautifully written you described your experience and the people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Renee. It was indeed a culturally rich experience. I’m so glad we went there. Such a beautiful place.

Alison

LikeLike

Great moments, unforgettable memories and beautiful photographs! These are what makes travel so special.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! It was all of that – great moments and unforgettable memories. We loved it there. Samoa is a little South Pacific gem.

Alison

LikeLike