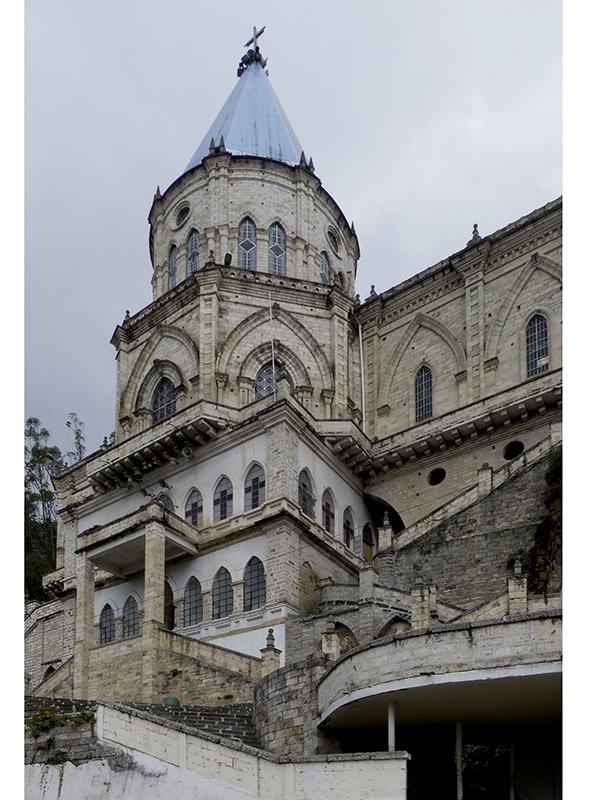

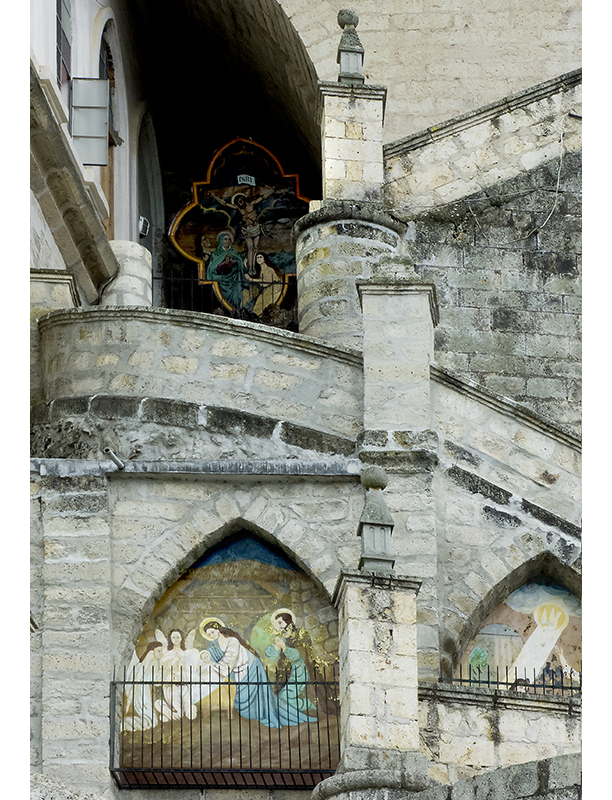

12-24 March 2014. To the northwest of Cuenca, past the town of Azogues, is the village of Biblían. High on a hill, overlooking Biblían sits a gorgeous fairytale palace, visible for miles.

It’s actually the Sanctuario de la Virgen del Rocio. Local legend has it that a priest’s prayer for rain was granted and so he built a small shrine to the Virgen del Rocio. The neo-Gothic church, built in the 1940’s right into the cliff face around the shrine, is a place of devotion for the faithful.

Travelling on we came to something a little more prosaic: a whole roasted pig. It’s a sight commonly seen throughout the highlands of Ecuador. Although ‘hornado’ (roast pork) is one of the staple dishes of the Ecuadorian diet, it is the roasted skin that’s eaten in this case. You can see the pig has lost its skin all down its left side. I wonder if the meat is eaten later?

The Cañari have inhabited the southern highlands of Ecuador for more than 3000 years. Historically they were one of the most important tribes in the region and Cuenca was their capital or main city for hundreds of years. They were a powerful tribe with fine skills in weaving, agriculture, pottery, and working with gold and silver. They lost to the Inca after a long-fought and bitter struggle, and later sided with the Spanish against the Inca. In the end, as we all know, the Spanish prevailed over all.

The majority of people are now of mixed race, but the culture and traditions are still maintained by a small number of indigenous Cañari (known as indigenas). Today most of the Cañari are farmers living in or near small remote villages. The town of Cañar has a population of about 10,000 and on Sunday, market day, everyone descends on the town for the important business of buying, selling and socializing. I sometimes suspect that the socializing, and strengthening of community ties, is the most important aspect of market days the world over.

We always seek out the local markets. Some of them are obviously set up for tourists, and for us have only a passing interest, in part because I suppose we feel a kind of low-grade guilt or discomfort at only looking, and in part because we feel uncomfortable with the sales pitch and pressure. At these markets we are interested in the beautiful and unique and often inventive crafts for sale though we never want to buy (except gifts occasionally). The quality of work is frequently incredibly good, and I don’t mean good considering they are made in third world countries. I mean good compared to anything in the world. Our experience of handmade crafts all throughout South America is that they often show an extraordinary quality. (The textiles of Otavalo come to mind). There are many cheap made-for-tourists knock-offs of course, but much very fine quality work can also be found.

Our favourite markets are the markets where the local population goes to shop, where the vendors come from miles around bringing their produce for sale, where you can see a man with a small grinder making flour right on the street,

where livestock, from guinea pigs to goats, from rabbits to cattle, is for sale,

where everyone gathers from the villages to connect and socialize, where the ordinary life of the people of the area happens before your eyes, where nothing is arranged for tourists and where everything goes on in exactly the same way as it has done for hundreds of years (except now they have motor vehicles and cell phones). Such is the Sunday market in Cañar. I think we were the only tourists there, and were afforded a sweet glimpse into the lives of the Cañari.

We enter from the corner of the main street and plunge straight into the crowd excited by the vibrant and purposeful atmosphere. There is a buoyant spirit of reconnection and friendship. At the same time the real purpose of the day, the buying and selling, pervades everything. All around us are goods and people: sacks and sacks of flours, grains and legumes where we first enter,

and behind that ropes and hardware for all purposes, and in another area fruits and vegetables. We plunge in to the melee.

The market covers several blocks and we wander for hours taking it all in.

We come to a large crowd gathered around an open-sided tent. Sitting behind a somewhat dilapidated model of the human body, a man speaks extensively and persuasively about the body, pointing to various parts of it, and to the potions he has. His audience listens attentively, seemingly spellbound. He encourages me to take photos. I do wish I could have understood him. He may have been a travelling ‘snake-oil’ charlatan. Or he may have been selling genuine natural remedies.

Those of you who have been following our South American journey know how important, and ubiquitous, hats are to the people of the Andes. Fedoras are to be found everywhere, stovepipes are not uncommon, and the Cholas of Bolivia have turned bowler hats into a jaunty fashion statement of national pride. Many wear straw hats, and in Ecuador at least, have them refurbished by painting them to make them last longer. I must also mention Panama hats, which are not from Panama at all, but are exclusively an Ecuadorian creation.

With grateful thanks to Judy Blankenship and her friend Ed Holmes, I managed to acquire some information about the white Cañari hats. White felt hats are not unique to the Cañari, but the shape and style seen here are. They are made over a form, and are delivered to market undecorated. The purchaser (usually women) then decorates the hat with ribbons, rosettes and tassels.

Sometimes, though not always, unmarried young women use long white ribbons to indicate that they are single. Men, women and children from about two years of age all wear the hats as protection from sun, rain and cold. There is a hat maker in the small town of Pelileo, and others in the bigger centres of Quito and Otavalo. Apparently they guard closely their hat-making secrets.

Shopping and visiting complete, people wait in line for the bus. Of course, except for their clothing it could be people waiting for a bus almost anywhere in the world.

Close by the town of Cañar are the ancient Cañari and Inca ruins of Inga Pirca. Surrounded by hills, and near the Cañar River, it was originally constructed by the Cañari as a fortress and a place of worship. The round temple indicates the moon worship of the Cañari, rather than the more angular structures of the Inca for sun worship. With the defeat of the Cañari by the Inca, it was converted to a Temple of the Sun, and is situated so as to catch the sun’s rays on the solstices and equinoxes.

After the defeat of the Cañari and the establishment of Tomebamba (now Cuenca) as the regional capital, the unpopular Inca needed outposts to defend themselves against the restive and discontented local population so the fortress of Inga Pirca (meaning simply Inca walls) was expanded and used for this purpose.

It doesn’t have the grandeur of other Inca sites we visited such as Machu Picchu and Pisac. Hard to get excited about it really. There was supposed to be an English-speaking guide, which might have helped, but none were available so we wandered around until it started raining and then we went home. I remember way back in the post about Rome I wrote that we don’t really give a toss about the ancient Romans and their empire and so the Forums and Palatine Hill were a little ho hum. Inga Pirca was like that for us. We were travelled out, saturated. If you’re truly into Inca ruins and haven’t yet seen Machu Picchu, Pisac, Cusco, and the other ruins in that area, you’ll probably love it. And it certainly does have a dignity and beauty of its own.

Next post: Galapagos revisited. Kenny and Anna from Taiwan, who we met on the Galapagos cruise, have kindly given us permission to share their exquisite photos.

All words and images by Alison Louise Armstrong unless otherwise noted

© Alison Louise Armstrong and Adventures in Wonderland – a pilgrimage of the heart, 2010-2015.

Great photos, as always, and I liked what you said about local markets. We’re the same – small town and non-touristy markets are the most interesting and authentic,

LikeLike

Thanks Shirley. We always seek out the markets – a chance to see real life. Also the back streets of a town. It’s amazing what you can see, and who you can meet, by wandering off the beaten track.

Alison

LikeLike

We also enjoy the local markets. Such a great way to become familiar with the culture.

LikeLike

Yes isn’t it? Best thing to explore, especially if you don’t know anyone local.

Alison

LikeLike

I really love your photos 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much ❤

Alison

LikeLike

Alison, your posts are like traveling the globe without leaving the comfort of home.

And your photos are just beautiful, as always.

Blessings,

Dani

LikeLike

Thanks Dani. That is great compliment!

Blessings to you too ❤

Alison

LikeLiked by 1 person

So, Alison, I have to ask – being the stylish person you are, did you get one of those hats?

LikeLike

No I did not, but now that you mention it I kinda wish I did. I can see me wearing such a hat (stylishly decorated of course) in the colder months of Vancouver. Never in buying mode while we’re travelling so didn’t even think of it.

Alison

LikeLike

“Shopping and visiting complete, people wait in line for the bus. Of course, except for their clothing it could be people waiting for a bus anywhere in the world.”

They couldn’t be from France 😉 Frech people don’t know how to line up hihi!

Great entry as always!

LikeLike

Thanks Sandra. Same in India – I think lining up is unheard of. They all just kind of crowd in and the pushiest wins 🙂

I will change it to *almost* anywhere in the world

C U in October!

Alison

LikeLike

See you in October! Want to hear about your travels live! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this wonderful experience. I’ve visited both Cuenca and Inga Pirca but have learnt so much more from your piece that my own wanderings taught me! I love your photos of the local people too that really capture a moment’s expression cross their faces.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, I’m glad you enjoyed it. I love photographing the people. For me that’s mostly what a place is about.

Alison

LikeLike

I lift my (very English), hat to you both in appreciation of your wonderful imagery and insights.

Very many thanks; once again, a truly delightful and engaging article.

Hariod.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Hariod for your lovely compliments. I loved all the different hats of the Andes – so unique, and so much variety.

Alison

LikeLike

Marvelous pictures, as always. Particularly enjoy the pictures of the hats, and your conviction that you want to stay away from the tourist markets and get into the heart of a city.

LikeLike

Thanks Felicity. We always go in search of the less touristy parts of town – generally makes for a richer experience.

Alison

LikeLike

You must miss these places pulsing with life and colour and those wonderful hats! Vancouver, beautiful city as it is, sounds definitely low-key and sleepy in comparison.

LikeLike

Oh we are very happy to be low-key at the moment – all this wonderful weather (except today :() and lots of family visits, and the Folk festival has been plenty.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison, one of the great strengths of this blog is the quality of your candid portraits – it’s something I must learn from and improve in my own photography. This was a fabulous study of the Cañari people and their hats!

James

LikeLike

Thanks James, that’s a lovely compliment. I’m sneaky with photos. I have a 600m zoom and I hold the camera at my waist and use the articulated monitor (rather than use the view finder where everyone can see what you’re doing). It precludes using a flash of course which can limit things, and I do use Photoshop where necessary to enhance photos. I love photographing the people of a place. Of course in India it’s very easy – people ask to have their picture taken, and even if not they’re never offended if you do.

Alison

LikeLike

Yay, Kenny and Anna from Taiwan, will look forward to their photos. However, something about this little town and local market appealed to me more than the others. I wonder why? (It certainly was not the roast pig…)

LikeLike

Thanks Pam, glad you found it appealing. We did too, even after having been to so many markets around the world. I love their hats 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

Hmmm, was I more serene as I just read this or were you more serene as you typed? It’s a lovely post and the pictures are divine, as always, but as I read I felt an extra quiet, calm something-something here. Well, whether it was me or you, or both of us, I am thoroughly enjoying it, and am wishing you continued peace.

LikeLike

Ah Kelly you are so perceptive. Don and I did a silent retreat las weekend and something shifted leading to a deeper presence, and a new internal calm. I’m still getting used to it 🙂

Thanks for your lovely compliments.

I hope the calm is you too!

Alison ❤

xox

LikeLike

Yummy! Your presence and calm blesses me.

Love to you.

LikeLike

What an interesting place! The people are quite colorful, literally and figuratively.

Don’t think I would order pork for dinner though–after the sight of the pig hanging out there, Perhaps a salad…

LikeLike

We were quite fascinated. They seemed to have a rich culture and to be proud of their traditions, and we loved the bright colours of the women’s clothes, and their hats. I wouldn’t eat the pork either, but you’d be extremely hard pressed to get a salad anywhere in South America. We were just dying for salad and fresh vegetables by the time we left. There’s certainly unique aspects to the diet in each country, and in different regions, but overall South America is a very meat and starch (potatoes and maize) kind of place.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison, your photos of the market are alway so intriguing. I love the one with the women lining the stair steps. And I think you really hit the nail on the head when you said, “I sometimes suspect that the socializing, and strengthening of community ties, is the most important aspect of market days the world over.”

How is your recovery going? I’m hoping that you’re ankle is much better.

All the best, Terri

LikeLike

Thanks Terri. I love taking unposed photos of people, and even better if they don’t know 🙂

My ankle is much better thanks, almost 100% and I can exercise again which feels wonderful – nothing like a little aerobic exercise to increase your energy!

Cheers, Alison

LikeLike

That’s wonderful Alison! So glad to hear that you are all healed. Yay! ~Terri

LikeLike

I agree that a farmers’ or central outdoor market gives a glimpse into daily lives and socializing.

Those varieties of hats are neat. Your photos really illustrate the range of common styles. Did you buy a felt hat?? 🙂

LikeLike

We loved all the different hat varieties in the Andes, but I do think my favourite has to be the white felt Cañari hats. I think they’re very stylish. No I didn’t buy one. And now I wish I had. I’m never in buying mode when we’re travelling except for gifts, or practical things like replacing t-shirts that have reached the end of their days.

Alison

LikeLike

Another great post, as has been said, but what the hell. I am blown away by the fact that that stone church was built into the side of the cliff as recently as 1940. My perspective is undoubtedly myopic, but it seems like architecture, materials and construction approaches had already become far more efficient and insubstantial in other parts of the world. Whether I’m being delusional or not, it suggests to me the power in placing priorities, and the richness that can come from shared observance of the sacred.

And the hats, which you touched upon… The hats! I am quite sure that if you put together a book chronicling your journeys, the chapter on hats alone would be a revelation. Another thought that struck me on all the hats and apparel was the relative lack of logos and branding. I don’t know how I failed to consciously notice their absence before. Perhaps color and pattern fulfill the function of collective differentiation, but in reflecting on what is joyful in these images, the absence of cartooned images and in-your-face slogans makes them that much more profound. So human and artful.

Michael

LikeLike

Thank you Michael. Isn’t that church wonderful?! I too thought it was much older; it seems to be such an integral part of the hillside. Some of the interior walls are the stone face of the cliff. I agree there’s a great richness that can come from shared observance of the sacred. And I am frequently moved by the palpable energy of devotion, often to tears. But then I also often think would people’s lives have been better enriched if that energy/money had gone to infrastructure like clean water, plentiful food, affordable housing, etc? This was what I first thought of when I saw the golden church in Quito – all that gold taken from the indigenous people to build a church, probably by their bare and hungry hands, while they lived in poverty. So in the end I don’t know what’s right – feed the soul or feed the body? I wish both didn’t seem like such a luxury for most of the world.

You overestimate my knowledge of Andean hats 🙂 – but they were certainly impossible to ignore.

I LOVE that there are no logos on their clothing, and refuse to buy any clothing that has the brand displayed. I think that if the company wants me to advertise for them they should pay me for it. What we see here, and throughout the Andes particularly, is a natural traditional style of dress with no fear of colour. I love that too!

Alison

LikeLike

You bring more colorful pics from distant lands 🙂 Love them all! Totally desktop wallpaper worthy!!! Guys, you never disappoint.

LikeLike

Thanks so much sb for your wonderful compliment. Wallpaper worthy! Wow. Thanks.

Alison ❤

LikeLike

😀

LikeLike

“The round temple indicates the moon worship of the Cañari, rather than the more angular structures of the Inca for sun worship.”

I can’t help but pause at these simple words pointing to layers of history and hidden meaning. This shift from moon to sun, from rounded to angular, hmmmm. Something mysterious; a riddle wishing to reveal itself. Thank you for such sharing, world shrinking, and heart expanding experiences you bring to my doorstep! xo! m

LikeLike

I thought the change from round to angular interesting too – from a softness and inclusiveness to something more strong and aggressive. The Cañari fought long and hard but were no match for the fierce Inca who had conquered many lands by this point. I have read that the fact that the temple catches the sun’s rays on the solstices and equinoxes owes more to the Cañari placement than the Inca. I think the Inca just found it convenient to convert it for their own religion in much the same way the Pantheon was converted from a pagan temple to a Christian Basilica and thus survived. And it is a riddle since I’ve seen round Inca temples, but much of their construction was certainly angular. As you say – mysterious. I sometimes think historians don’t know as much as they think they know 🙂

xox

LikeLike

You and Don could probably do a book on the hats of South America, Alison. 🙂 I also liked the duck photo and think it would make an interesting abstract poster. As always your photos and commentary are quite interesting and educational. Peggy and I just got back from our Kayaking adventure out of Fort McNeil on Vancouver Island. Lots of beauty and orcas. –Curt

LikeLike

Thanks Curt. By duck photo do you mean the box of ducklings or the punk ducks (geese?) from the previous post.

Michael suggested a chapter on hats, now you want a whole book ?! You both seriously overestimate my knowledge of hats! 🙂

Oh I bet you had an amazing time kayaking there – beautiful part of the world. I hope I get to read about it soon. And see the pictures 🙂

Alison

LikeLike

I was referring to the little box of duckies. 🙂 Yes, we had a great time kayaking and I will be blogging about it. First up, Burning Man, however. –Curt

LikeLike

Have a great time!

LikeLike

I too love visiting local markets when I travel! They are always so full of life and a great way to see a bit of real life in the place where you’re visiting. As always, your photos are incredible!

LikeLike

Thanks re the photos Mo. Markets are just about the only thing where you get to see real life, unless of course you get to meet and connect with the locals, or someone who lives there. Just read your great account of your time in Belgrade – makes me want to go there.

Alison

LikeLike

Hello I just came across your post.

My heritage is cañari and I was born in the U.S.

I’m always visiting my relatives that live there and your post describes my family’s hometown right on point.

awesome blog!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Linda. This is the best kind of compliment I could possibly get. I’m fascinated by the different cultures we visit, and it was no different with the Cañar. It was wonderful to be able to find our more about them, and to share it.

Alison

LikeLike

Hi,

Just came across your page and its nice to see pictures from different places. Can you explain who the Canari are, like are they Quechua or not? If not, how can you tell the difference? Your pictures are nice, keep it up! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Maria. The Cañari are not Quechua. The Incas were Quechua, the Cañari were a different group, or tribe I suppose, that was conquered by the Inca. I have no idea how to tell the difference except for their clothing and location in modern times. Many of the posts on Peru talk about the Inca. You’ll see that their clothing is quite different from the Cañari and varies from village to village.

Alison

LikeLike

Are the Quechua people quite a large number in Ecuador like in Peru? And are the Otavalos the largest native group in the country as well are they Quechua? Please let me know as I like learning about culture and demographics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry Maria, but I really don’t know. I would guess that the Otavalos are not Quechua, and that there are more Quechua in Peru than in Ecuador, but I don’t know for sure. Sorry I can’t be more help.

Alison

LikeLike